LAVINIA GREENLAW

‘Here,’ he thought, ‘is where we differ from women; they have no sense of romance.’

Ralph Denham in Virginia Woolf’s

Night and Day

He had stylised himself – life was easier that way.

Graham Greene, The Ministry of Fear

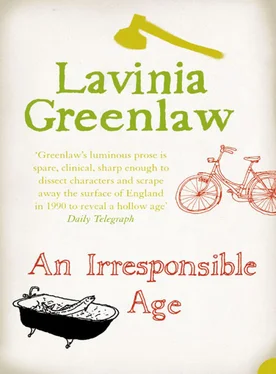

COVER

TITLE PAGE

EPIGRAPH

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

TWENTY-SIX

TWENTY-SEVEN

TWENTY-EIGHT

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

PRAISE

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

‘So of course there was nothing for it but to leave.’

Juliet Clough had been about to sit down at her desk but now felt that although this was her room, she had interrupted something and ought to wait. She remained in the doorway while the voice coming from the other side of the wall continued: ‘Yes … well, thank you … No, absolutely. Of course … She’s just so … All the time these days … I do try but it’s just … You’re absolutely right … If only she could see it like … It’s just that I … You know … You do understand … Thank you … thank you …’

Juliet crept to her chair and lowered herself into it. The conversation appeared to have finished but she sat for several minutes, concentrating on staying still. Whoever he was, he must not hear her listening.

A telephone rang. Juliet tensed and leant towards the wall, only this time the man did not pick it up. Her own telephone rang so rarely that it took her a moment to realise that it was hers and not his that was ringing now. If she answered it, he would hear her and then he would know that she had been listening. She grabbed the receiver and moved across the room as far as the cord would allow.

‘Hello. Yes, it is. The Shipping Office, yes.’ She was crouching on the floor. ‘No, I can’t speak up. The opening? She’ll be delighted. I’ll tell her. Yes, I know who you are. Yes, I can spell it. Goodbye.’

So as not to have to speak again, she went outside to have a cigarette. She slipped out through the firedoors at the back of the building and hurried along the path by the river, relieved that she had not had to encounter him.

She stretched over the broad stone wall, trying to see the mud whose smell oozed in under her office door at low tide, only she wasn’t tall enough to manage it. The roll-up she had cobbled together with cold fingers kept going out, but she needed to smoke and to shake off the effect of the man who had turned up on the other side of the wall. So of course there was nothing for it but to leave. The line was familiar. Had she read it? Heard it? Never said it, though. That sort of thing hadn’t come up.

It was nothing, just something she wasn’t used to. Tania had had an odd corner at the back of the gallery turned into a self-contained unit to be rented out. Juliet had forgotten about it and could not imagine who might want it. Most of the nearby offices were unoccupied still – spice warehouses hastily converted for lease as work spaces, as if all it took was a rearrangement of letters.

Some of these streets were lined with blind walls while others were overlooked by tall windows and jutting iron hoists, suggesting such a scale of effort and industry that Juliet imagined the spices had once arrived here by the ton, in great sacks and chests that had to be heaved up and in. What surprised her most was the romance of the air, always a little stormy, into which the walls leaked the scent of nutmeg, coriander and cloves after rain. She was too wary and proprietorial to tell anyone about that.

It was January 1990, the end of a pugnacious decade and the tail end of a particularly long century. The city experienced a loss of tension and with it, a loss of momentum. Much that had been started had been set aside, but London was not a place to abandon an idea just because it proved to be a bad one. Attention wandered until no one could remember who had begun what or why, but sooner or later things would fall into place, although this usually took longer and cost more than anyone had predicted.

This in-between area east of the Square Mile and south of the river was now a blank space in the A to Z marked ‘under development’. It was being reconstructed in an optimistic mirroring of the Docklands project which was transforming the river’s north bank. The sidestreets around the hopeful, isolated gallery in which Juliet worked had been built for barrows and carts and did not encourage traffic, and so the cars belonging to the few who lived there got stuck negotiating tight corners. Juliet never saw these people in the streets, where there was nothing for them. They drove away early and came back late to sit behind glass and gaze across the river at the homes they had really wanted.

Juliet didn’t notice what was happening on the river because it was all so routine. Police launches veered waspishly about while barges slunk up and down, so low-lying they might be about to go under. What lay beneath their tarpaulins? What was left for them to transport? Dingy sightseeing cruisers ploughed back and forth, the wind garbling their amplified commentaries: ‘HMS Belfast … battle of … Elizabeth … The Tower … Docklands … Boom …’ Someone always waved and someone on shore, though never Juliet, always waved back.

On the north bank, the tallest office block in Europe had just been built on a redundant wharf. The roads that would lead towards it were as yet unmade. To the west was Traitor’s Gate where water splashed against an iron grid. Juliet could imagine those who acted against the state being taken through on a boat, blindfolded, hands tied, gagged; terrorists, perhaps.

A city with so little space and so much history that it had become its own obstruction. Juliet had wanted to study in London because she believed herself to be solitary, unknowable and footloose, and that this was the place most likely to confirm that for her. She could not say that it had, but nor did she care. She looked down into a swirl of rotten timber, industrial froth and brick-pink stain. She couldn’t care less about her stupid job in this gallery where she had to put up with things like the man through the wall. She was going to America.

‘I had no idea you could be so boring.’

For a moment Juliet thought it was a different voice: it was as light as before but needle sharp.

‘Calm down. I know you’re not shouting, Bar, but you need to calm down. And do stop swearing all the time. It’s not terribly attractive … I know … We must … we will … of course, sweetie … try to understand … Buck up, why don’t you … That’s better. Good girl. Now you’ve got work to do, haven’t you? Good girl. I’ll drop by and see you tonight … No, it was a triumph. You were a triumph. What do you mean let you down? What on earth would you need me there for when you were surrounded by all your … I’m going to put the telephone down if you start. You really can be very stupid … The reason I got this place was to be able to …’

Читать дальше