If ahamkara (ego) is considered to be one end of a thread, then antaratma (Universal Self) is the other end. Antahkarana (conscience) is the unifier of the two.

The practice of yoga integrates a person through the journey of intelligence and consciousness from the external to the internal. It unifies him from the intelligence of the skin to the intelligence of the self, so that his self merges with the cosmic Self. This is the merging of one half of one’s being ( prakrti ) with the other ( purusa). Through yoga, the practitioner learns to observe and to think, and to intensify his effort until eternal joy is attained. This is possible only when all vibrations of the individual citta are arrested before they emerge.

Yoga, the restraint of fluctuating thought, leads to a sattvic state. But in order to restrain the fluctuations, force of will is necessary: hence a degree of rajas is involved. Restraint of the movements of thought brings about stillness, which leads to deep silence, with awareness. This is the sattvic nature of the citta.

Stillness is concentration ( dharana ) and silence is meditation ( dhyana ). Concentration needs a focus or a form, and this focus is ahamkara, one’s own small, individual self. When concentration flows into meditation, that self loses its identity and becomes one with the great Self. Like two sides of a coin, ahamkara and atma are the two opposite poles in man.

The sadhaka is influenced by the self on the one hand and by objects perceived on the other. When he is engrossed in the object, his mind fluctuates. This is vrtti. His aim should be to distinguish the self from the objects seen, so that it does not become enmeshed by them. Through yoga, he should try to free his consciousness from the temptations of such objects, and bring it closer to the seer. Restraining the fluctuations of the mind is a process which leads to an end: samadhi. Initially, yoga acts as the means of restraint. When the sadhaka has attained a total state of restraint, yogic discipline is accomplished and the end is reached: the consciousness remains pure. Thus, yoga is both the means and the end.

(See I.18; II.28.)

1.3 tatla drastuh svarupe avasthanam

| tada |

then, at that time |

| drastuh |

the soul, the seer |

| svarupe |

in his own, in his state |

| avasthanam |

rests, abides, dwells, resides, radiates |

Then, the seer dwells in his own true splendour.

When the waves of consciousness are stilled and silenced, they can no longer distort the true expression of the soul. Revealed in his own nature, the radiant seer abides in his own grandeur.

Volition being the mode of behaviour of the mind, it is liable to change our perception of the state and condition of the seer from moment to moment. When it is restrained and regulated, a reflective state of being is experienced. In this state, knowledge dawns so clearly that the true grandeur of the seer is seen and felt. This vision of the soul radiates without any activity on the part of citta. Once it is realized, the soul abides in its own seat.

(See I.16, 29, 47, 51; II.21, 23, 25; III.49, 56; IV.22, 25, 34.)

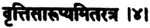

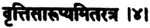

I.4 vrtti sarupyam itaratra

I.4 vrtti sarupyam itaratra

| vrtti |

behaviour, fluctuation, modification, function, state of mind |

| sarupyam |

identification, likeness, closeness, nearness |

| itaratra |

at other times, elsewhere |

At other times, the seer identifies with the fluctuating consciousness.

When the seer identifies with consciousness or with the objects seen, he unites with them and forgets his grandeur.

The natural tendency of consciousness is to become involved with the object seen, draw the seer towards it, and move the seer to identify with it. Then the seer becomes engrossed in the object. This becomes the seed for diversification of the intelligence, and makes the seer forget his own radiant awareness.

When the soul does not radiate its own glory, it is a sign that the thinking faculty has manifested itself in place of the soul.

The imprint of objects is transmitted to citta through the senses of perception. Citta absorbs these sensory impressions and becomes coloured and modified by them. Objects act as provender for the grazing citta , which is attracted to them by its appetite. Citta projects itself, taking on the form of the objects in order to possess them. Thus it becomes enveloped by thoughts of the object, with the result that the soul is obscured. In this way, citta becomes murky and causes changes in behaviour and mood as it identifies itself with things seen. (See III.36.)

Although in reality citta is a formless entity, it can be helpful to visualize it in order to grasp its functions and limitations. Let us imagine it to be like an optical lens, containing no light of its own, but placed directly above a source of pure light, the soul. One face of the lens, facing inwards towards the light, remains clean. We are normally aware of this internal facet of citta only when it speaks to us with the voice of conscience.

In daily life, however, we are very much aware of the upper surface of the lens, facing outwards to the world and linked to it by the senses and mind. This surface serves both as a sense, and as a content of consciousness, along with ego and intelligence. Worked upon by the desires and fears of turbulent worldly life, it becomes cloudy, opaque, even dirty and scarred, and prevents the soul’s light from shining through it. Lacking inner illumination, it seeks all the more avidly the artificial lights of conditioned existence. The whole technique of yoga, its practice and restraint, is aimed at dissociating consciousness from its identification with the phenomenal world, at restraining the senses by which it is ensnared, and at cleansing and purifying the lens of citta , until it transmits wholly and only the light of the soul.

(See II.20; IV.22.)

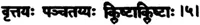

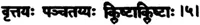

I.5 vrttayah pañcatayyah klista aklistah

I.5 vrttayah pañcatayyah klista aklistah

| vrttayah |

movements, modification |

| pañcatayyah |

fivefold |

| klista |

afflicting, tormenting, distressing, painful |

| aklistah |

untroubling, undisturbing, unafflicting, undistressing, pleasing |

The movements of consciousness are fwefold. They may be cognizable or non-cognizable, painful or non-painful.

Fluctuations or modifications of the mind may be painful or non-painful, cognizable or non-cognizable. Pain may be hidden in the non-painful state, and the non-painful may be hidden in the painful state. Either may be cognizable or non-cognizable.

When consciousness takes the lead, naturally the seer takes a back seat. The seed of change is in the consciousness and not in the seer. Consciousness sees objects in relation to its own idiosyncrasies, creating fluctuations and modifications in one’s thoughts. These modifications, of which there are five, are explained in the next sutra. They may be visible or hidden, painful or not, distressing or pleasing, cognizable or non-cognizable.

Читать дальше

I.4 vrtti sarupyam itaratra

I.4 vrtti sarupyam itaratra I.5 vrttayah pañcatayyah klista aklistah

I.5 vrttayah pañcatayyah klista aklistah