Normal breath flows irregularly, depending on one’s environment and emotional state. In the beginning, this irregular flow of breath is controlled by a deliberate process. This control creates ease in the inflow and outflow of the breath. When this ease is attained, the breath must be regulated with attention. This is pranayama.

Prana means life force and ayama means ascension, expansion and extension. Pranyama is the expansion of the life force through control of the breath. In modern terms, Prana is equated to bio-energy and works as follows. According to samkhya and yoga philosophies, man is composed of the five elements: earth, water, fire, air and ether. The spine is an element of earth and acts as the field for respiration. Distribution and creation of space in the torso is the function of ether. Respiration represents the element of air. The remaining elements, water and fire, are by nature opposed to one another. The practice of pranayama fuses them to produce energy. This energy is called Prana: life force or bio-energy.

Ayama means extension, vertical ascension, as well as horizontal expansion and circumferential expansion of the breath, lungs and ribcage.

Pranyama by nature has three components: inhalation, exhalation and retention. They are carefully learned by elongating the breath and prolonging the time of retention according to the elasticity of the torso, the length and depth of breath and the precision of movements. This pranayama is known as deliberate or sahita pranayama as one must practise it consciously and continuously in order to learn its rhythm.

To inhalation, exhalation and retention, Patañjali adds one more type of pranayama, that is free from deliberate action. This pranayama, being natural and non-deliberate, transcends the sphere of breath which is modulated by mental volition. It is called kevala kumbhaka or kevala pranayama.

The practice of pranayama removes the veil of ignorance covering the light of intelligence and makes the mind a fit instrument to embark on meditation for the vision of the soul. This is the spiritual quest.

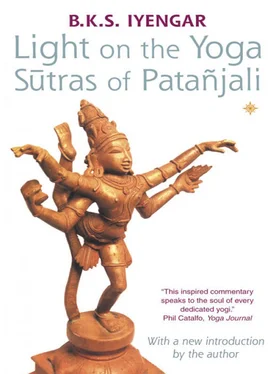

(For further details see Light on Yoga, The Art of Yoga and Light on pranayama (HarperCollinsPublishers) and The Tree of Yoga (Fine Line Books).

Through the practices of yama, niyama, Asana and pranayama, the body and its energy are mastered. The next stage, pratyahara , achieves the conquest of the senses and mind.

When the mind becomes ripe for meditation, the senses rest quietly and stop importuning the mind for their gratification. Then the mind, which hitherto acted as a bridge between the senses and the soul, frees itself from the senses and turns towards the soul to enjoy its spiritual heights. This is the effect of disciplines laid out in sadhana pada. Pratyahara , the result of the practice of yama, niyama, Asana and pranayama, forms the foundation for dharana, dhyana and samadhi. Through practice of these five stages of yoga, all the layers or sheaths of the self from the skin to the consciousness are penetrated, subjugated and sublimated to enable the soul to diffuse evenly throughout. This is true sadhana.

In samadhi pada , Patañjali explains why the intelligence is hazy, sluggish and dull, and gives practical disciplines to minimize and finally eliminate the dross which clouds it. Through these, the sadhaka develops a clear head and an untainted mind, and his senses of perception are then naturally tamed and subdued. The sadhaka’s intelligence and consciousness can now become fit instruments for meditation on the soul.

In vibhuti pada , Patañjali first shows the sadhaka the need to integrate the intelligence, ego and ‘I’ principle. He then guides him in the subtle disciplines: concentration ( dharana ), meditation ( dhyana ) and total absorption ( samadhi). With their help, the intelligence, ego and ‘I’ principle are sublimated. This may lead either to the release of various supernatural powers or to Self-Realization.

Patañjali begins this pada with dharana , concentration, and points out some places within and outside the body to be used by the seeker for concentration and contemplation. If dharana is maintained steadily, it flows into dhyana (meditation). When the meditator and the object meditated upon become one, dhyana flows into samadhi. Thus, dharana, dhyana and samadhi are interconnected. This integration is called by Patañjali samyama. Through samyama the intelligence, ego and sense of individuality withdraw into their seed. Then the sadhaka’s intelligence shines brilliantly with the lustre of wisdom, and his understanding is enlightened. He turns his attention to a progressive exploration of the core of his being, the soul.

Having defined the subtle facets of man’s nature as intelligence, ego, the ‘I’ principle and the inner self, Patañjali analyses them one by one to reveal their hidden content. He begins with the intellectual brain, which oscillates between one-pointed and scattered attention. If the sadhaka does not recollect how, where and when his attention became disconnected from the object contemplated, he becomes a wanderer: his intelligence remains untrained. By careful observation, and reflection on the qualities of the intelligence, the sadhaka distinguishes between its multi-faceted and its one-pointed manifestation, and between the restless and silent states. To help him, Patañjali explains how the discriminative faculty can be used to control emerging thought, to suppress the emergence of thought waves and to observe the appearance of moments of silence. If the sadhaka observes and holds these intermittent periods of silence, he experiences a state of restfulness. If this is deliberately prolonged, the stream of tranquillity will flow without disturbance.

Holding this tranquil flow of calmness without allowing the intelligence to forget itself, the seeker moves towards the seer. This movement leads to inner attention and awareness, which is in turn the basis for drawing the consciousness towards integration with the inner self. When this integration is established, the seeker realizes that the contemplator, the instrument used for contemplation, and the object of contemplation are one and the same, the seer or the soul: in other words, subject, object and instrument become one.

Bringing the intelligence, buddhi , to a refined, tranquil steadiness is dharana. When this is achieved, buddhi is re-absorbed by a process of involution into the consciousness, citta , whose inherent expression is a sharp awareness but without focus. This is dhyana. The discrimination and unwinking observation which are properties of buddhi must constantly be ready to prevent consciousness from clouding and dhyana from slipping away. Buddhi is the activator of pure citta.

When the sadhaka has disciplined and understood the intelligence, the stream of tranquillity flows smoothly, uninfluenced by pleasure or pain. Then he learns to exercise his awareness, to make it flow with peace and poise. This blending of awareness and tranquillity brings about a state of virtue, which is the powerful ethic, or sakti, of the soul, the culmination of intelligence and consciousness. This culturing of intelligence is an evolution, and virtue is its special quality. Maintenance of this civilized, cultured, virtuous state leads to a perfect propriety, wherein the intelligence continues to be refined, and the sadhaka moves ever closer to the spiritual zenith of yoga.

Читать дальше