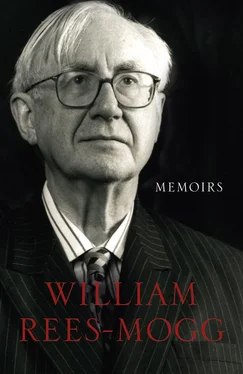

My political ambitions were already well formed. I believed I would become a political lawyer. I planned to read for the bar (I actually joined Gray’s Inn in 1948 or 1949), and to stand for Parliament. My imagination was fixed on a career as a Member of Parliament. I have always enjoyed politics, political company, debate, argument, even committee meetings. To me it is a stimulating and natural environment.

Shirley Williams once described me, in a flattering phrase, as ‘a young sage’ at Oxford, someone whom people would seek out for advice on matters relating to their own careers. Robin Day was the guru of younger Oxford politicians, advising them when to stand and for what office, but I studied the game of Oxford careerism with almost as much fascination as he did. I used to lunch with Robin Day at the Committee table in the Oxford Union. Later in life we lunched together at the Garrick Club. When Robin died I made a calculation that I had lunched with him more often than with anyone else outside my family. We always talked politics.

I got off to an early start in seeking political office at Oxford, as did our son Jacob in the late 1980s. He became President of OUCA and Librarian, though not President, at the Oxford Union. At the end of my first term I was elected to the Committee of OUCA. One of the senior members of the Committee was Margaret Thatcher and in the summer term she stood for the office of President. There were eleven members of the Committee with the right to elect the President. I voted for Margaret Roberts, as she then was, and she was elected by – as I remember it – seven votes to four.

She invited me to be the Meetings Secretary for the following term and I accepted with some glee. It would have meant greeting the outside speakers, who ranged between retired Cabinet Ministers and the rising young stars of the party, such as Reggie Maudling. I also looked forward to working for Margaret, who seemed in the immediate future to be the leading figure in Oxford Conservative politics and whom I liked.

This agreeable prospect was taken away from me when Sandy Lindsay, the Master of Balliol, who was made a Labour peer in 1947, decided to give my place in the college to a demo-bilized ex-serviceman. This meant that I only had two terms at Balliol in 1946, and I had to do my own National Service in the middle of my time at Oxford, which I resented. It was indeed contrary to the commitment the college had made when I came up. I was not able to take up my post as Meetings Secretary and had to go round to Somerville College to apologize to Margaret for my inability to accept her offer. In retrospect, I naturally regret not having worked more closely with her. When I returned to Oxford, two years later, she was in the hierarchy of ex-Presidents. By the time I became President of OUCA myself she had gone down from the university. Nevertheless, we retained a friendly acquaintance, which always gave me access after she became Leader of the Opposition and Prime Minister. I was not a member of the inner team of friends and advisers, but I think I was regarded, if rather remotely, as ‘one of us’. We never imagined at that time that Margaret was to become the first woman Prime Minister, though we knew how disciplined she was and how determined to achieve her objectives.

In 1946–8, I served two years in the RAF. The first winter was that of the 1947 fuel crisis. For most of those who lived through it, 1947 was one of the most unpleasant years of their lives. It started with an exceptionally cold winter in which supplies of coal ran out. These were fuelless days, electric fires burned only a dull red, and crowds suddenly discovered the fascination of tropical plants at Kew Gardens and tropical birds at various zoos around the country.

The fuel crisis broke the reputation of the Attlee Government for administrative competence. For years afterwards the Conservative Party speaker’s handbook carried a much-loved quotation from Emmanuel Shinwell: ‘There will be no fuel crisis, I am the Minister for Fuel and Power and I ought to know.’

I spent that winter as a National Service clerk in a Nissen hut at Flying Training Command Headquarters in Reading, Berkshire. We burned anything we could lay our hands on, except the snooker table, in an effort to keep the hut warm; we failed.

In the spring of 1948, I was sent on a course to Wellesbourne Mountford in Warwickshire to be turned into an acting sergeant in the RAF Education Corps. That I enjoyed.

Wellesbourne Mountford is situated close to Stratford-upon-Avon where I went to the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre; and I managed to stay with my cousins who then lived in the beautiful village of Clifford Chambers. Their house was said to have a rather sad association with Shakespeare. In 1616 he went there for a drinking party, returned home flushed with mulled wine, caught a chill which turned to pneumonia, and died. I do not know whether the story is true.

We had a splendidly crazy wing commander who was in charge of the course. He was concerned that we should have brightly polished boots, something I was still no good at. He told us a long and rambling story about a Canadian Mountie who was sent into the wilderness to capture an outlaw. It took him three years to find his man and three years to bring him back. Nevertheless, when he returned with his prisoner, he walked into his station with his Mountie uniform impeccably pressed and his boots shining like the sun.

As the education sergeant when I returned to the Reading headquarters I was not exactly fully employed. Consequently, I arranged to have tutorials on seventeenth-century history at Reading University, for which my tutor was paid three guineas a time.

I tried, and failed, to teach an illiterate WAAF recruit to read. I taught young officers general knowledge for their officer’s promotion exam. I remember telling them, with all the authority of a nineteen-year-old, that they would acquire an excellent grasp of current affairs if they read The Times every morning over breakfast.

I drafted a general knowledge quiz to find out what, if anything, they did know. That project had to be dropped when I put the quiz in front of my education officer, who was a squadron leader. One of my multiple-part questions required the candidate to sort biblical characters into the Old and New Testaments. Unfortunately, the squadron leader had not read his Bible. He thought Moses was a figure in the New Testament, and scolded me for setting a quiz which he regarded as unreasonably difficult.

In the sergeants’ mess we drank our beer and the occasional whisky and soda. I was the only teenager in a group of middle-aged men. They saw my life as quite divorced from their concerns, but we wished each other well.

The following year, I left the RAF and returned to Oxford University. As a sergeant I fear that I had failed to impress my Commanding Officer. He wrote a reference in my leaving book: ‘Sergeant Rees-Mogg is capable of performing routine tasks under close supervision.’ I only wish that were true.

It was the autumn of 1948 when I returned to Oxford. I was now twenty. I had had the advantage of two years in the RAF, which had transformed me from a callow recruit to a sergeant in Education. I had kept in touch with Oxford life through my friendship with Clive Wigram, who was himself elected as President of the Union. In the spring of 1948, I came up to Oxford for the last time wearing my RAF uniform with its largely unpolished boots. Clive and I went to watch some college races on the river. We met two delightful girls, both of whom were acquaintances of Clive. The dark-haired one was Val Mitchison, daughter of Naomi Mitchison, the novelist, later to become Val Arnold-Foster; the blonde was Shirley Williams, the daughter of another novelist, Vera Brittain. I remember thinking what a delightful place Oxford was, if one could stroll the towpath and meet such delightful young women. I did not realize that Val and Shirley had already become stars of Oxford society.

Читать дальше