In the summer, the war in Europe came to an end. Rather to my surprise, Birley asked me to stay on for an extra term and be Head of School. I had not been considered a likely candidate for the job, and, in any case, everyone assumed I was leaving. I was conspicuously unathletic. I was a thorn in the side of my house-master, who was opposed to the whole idea. I was seen in the school as a weedy intellectual, and there were doubts as to whether I could maintain discipline. Few headmasters other than Birley would have considered it. I think that part of his motivation was the desire to show that an intellectual could be Head of School.

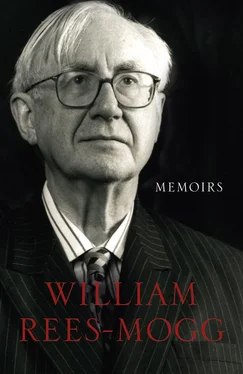

I do not think that I made a particularly good one. I compensated for my apparent lack of authority by being too decisive in some cases. The benefit of my being Head of School was not to Charterhouse but to me. I would previously have thought of myself as the sort of person who edits the school magazine but does not become the Head of School. My self-image came to include the idea of exercising authority. I have never subsequently found it worrying to handle the political relationships in such positions of authority as I have held. As Editor of The Times or as Chairman of the Arts Council, I have found the simple leadership skills which I first learned at Charterhouse were useful, and if I made some of the mistakes of the learning process while I was still at school, that is as it should be.

Chapter Six

Everyone Wants to Be Attorney General

I went up to Balliol in January 1946, just after the war. Balliol, a left-wing college, was then full of Labour triumphalism, following the General Election in the summer of 1945. The mood lasted about a year to the summer of 1946. It was quite unlike the political mood at any other time in my life. The Labour majority was a large one, people believed that this was a revolutionary event; they believed that the old ways of doing things had been thrown out. It was widely felt that the conservatism of the pre-war era had been not only morally repugnant, but also intellectually contemptible; it was a more complete ideological rejection than that of 1997. It was further held that figures like William Beveridge and J. Maynard Keynes had shown how it was possible to run society in a much more scientific and effective way. Conservatism was dead, and disreputable; the future lay with Attlee socialism, Keynesianism and the Beveridge Report. I did not agree.

Ideologically I was swimming against the tide in post-war Balliol. I took the view, best set out in Hayek’s book The Road to Serfdom , that universal state controls, including substantial state ownership and very high taxation, involved a serious loss of liberty. I held the connected belief that liberty was the key to economic and social development and that, by restricting liberty, Britain was putting shackles on its future performance. Margaret Thatcher, an Oxford contemporary and acquaintance, was taking the same view at the same time and in the same environment, but in 1946 we were a small minority, either among students or in Britain as a whole.

Balliol itself possessed a set of values which was distinct from the other Oxford colleges. It was a strange mixture. There is an extremely attractive feeling that Balliol is a special place, that there is a friendship throughout Balliol which crosses the boundaries of opinion. On the other hand, there was a self-congratulatory side to some Balliol men, which must have seemed rather ridiculous to the outside world. Balliol was, indeed, attracting and producing the best undergraduates. It was regarded as the academic college and merited this reputation. The Norrington Table had not yet been brought into existence, but Balliol was getting, fairly effortlessly, a high quota of Firsts. The many brilliant undergraduates included George Steiner, the literary critic, Bernard Williams, the philosopher and future Provost of King’s, and, among distinguished lawyers, George Carman, Lord Hutton and Lord Mayhew.

Among my first actions after I arrived at Oxford was to join the Oxford Union and the Oxford University Conservative Association (OUCA). The Union was the key institution in my life at Oxford. When I arrived it was dominated by people who had come back from the war. Being only seventeen, I was a schoolboy among people who were ex-officers and had been in battle. It was quite difficult to get myself into, and succeed, in a society which was dominated by people with much greater experience. I countered this by being very active indeed, not only managing to get myself elected, after only my first term, to the Committee of the Conservative Association, but also, at the end of my second term, to the Library Committee at the Union. I was an eager beaver, running round, working on university politics and getting to know people.

Ever since I had been at Charterhouse, where I founded a Conservative Society, I had sought out senior politicians as part of a learning process; they were almost a continuation of my school teachers, and were often generous with their time. I wrote to Leslie Hore-Belisha after the Conservative defeat in 1945, when he had lost his seat. Before the war, he had been, briefly, the great modernizer of British politics. In the National Governments of the later 1930s he modernized the transport system, introducing driving tests, the Highway Code and pedestrian crossings, marked by lights which were known for many years as Belisha beacons. Next, he was appointed to, and modernized, the War Office. He retired some twenty of the senior officers of the army, appointed Lord Gort as a new broom, and prepared the British Army for war in 1939. Without Belisha’s reforms the army could scarcely have formed the British Expeditionary Force in 1939, or, indeed, had the resilience to escape from Dunkirk.

These reforms were a material achievement, for which he was not much thanked. The old guard almost always wins in the end. Anti-Jewish prejudice was used to destroy Hore-Belisha. Early in 1940, he went as Minister for War to review the defences in France. He observed, and reported to the Cabinet, that there was a gap at the end of the Maginot Line. The French complained. Neville Chamberlain, with relief, took the opportunity to dismiss Belisha. Those who called him ‘Horeb-Elisha’ and ‘the Jew Boy’ had won.

I think Leslie Hore-Belisha saw himself as a second Disraeli. He was a brilliant speaker, a very modern publicist and a Minister capable of radical reorganization of his department. I cannot remember just how I first met him, but when I was at Oxford I attached myself with enthusiasm to his unfortunately waning star. I canvassed for him in Coventry South, a seat he failed to win back for the Conservatives in 1950. I exchanged lunches with him, going to his Lutyens house behind Buckingham Palace; we corresponded when I was in the RAF. He, too, had been President of the Oxford Union when he was at Oxford. By the 1950s he had very few disciples, and I think he was pleased to have a supporter. I learned a good deal from him.

I must have started the correspondence about the same time as I won the Brackenbury Scholarship, and presumably made some expression of my own political ambitions. At any rate, I remember one striking sentence in his reply which reflected both his own adolescent ambitions and what he saw as mine. ‘At the age of sixteen,’ he wrote, ‘everyone wants to be Attorney General.’ I remember a few other of his remarks. He told me that the perfect length for a speech in the House of Commons was no more than eight minutes; after that one would lose the attention of the House. His old seat had been Devonport, which in 1945 was won by Labour. He decided to move to the marginal seat of Coventry South, and commented of Devonport, ‘if they don’t want me, they shan’t have me’.

Читать дальше