Drawing of the constructional details of the traditional ‘hovel’ type of updraught bottle kiln. From Post-Med. Arch., Vol. 42, Pt 1, p. 205 (2008)

Plan of the purpose-built grounds surrounding the Quaker asylum at Brislington House, Bristol. From Rutherford, Landscapes , Vol. 5, No. 2 (2004), p. 30

Outline drawing of a later nineteenth century triangular blue cotton neckerchief. From Oleksy, Post-Med. Arch., Vol. 42, Pt 2, p. 293

Hand-carved model boat found in a large void beneath Court 3, Parliament House, Edinburgh. From Oleksy, Post-Med. Arch., Vol. 42, Pt 2, p. 296 (2008)

Map of Harwich Basin in the early eighteenth century. From Post-Med. Arch ., Vol. 42, Pt 2, p. 232

The defensive landscape at Landguard Fort, near Harwich, Suffolk. From Meredith, Post-Med. Arch ., Vol. 42, Pt 2, p. 235 (2008)

A composite plan, based on contemporary sources showing the main areas of activity at the Norman Cross (Peterborough) ‘Depot’, or prisoner-of-war camp

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and would be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in future editions.

Acknowledgements

FROM THE MOMENT I began this four-volume archaeological history of Britain I knew that, when I ventured outside my own field of expertise in later prehistory, I would have to rely on the cooperation and goodwill of many colleagues. But instead of encountering silence or, worse, resentment, I was astonished by the way medievalist scholars took me under their wing and made the task of writing Britain ad and Britain in the Middle Ages such a pleasure. For the present work I have had to draw on the knowledge of many post-medievalists and yet I have still to detect any impatience with my ceaseless enquiries. Two people who have had to bear the brunt of my curiosity are Drs Marilyn Palmer and Audrey Horning, both colleagues of mine in the School of Archaeology and Ancient History at the University of Leicester. They gave me informal seminars, sometimes even without the benefit of lunch, which helped me turn my face in what I hope has proved the right direction. Thank you both: my gratitude knows no bounds.

Michael Douglas, series editor at Time Team , shares my interest in the archaeology of more recent periods and played a major part in arranging the excavation of the Risehill navvy camp, North Yorkshire, and the Norman Cross prisoner-of-war Depot, Peterborough. While in Yorkshire, Bill Bevan was a great source of references and advice. At Norman Cross, Ben Robinson, the Peterborough City Archaeologist, was as ever amiable and authoritative, and Dr Henry Chapman, the Time Team surveyor, helped me acquire plans of the Norman Cross Depot site in advance of the full publication, which was scheduled to appear after my own manuscript’s deadline. Dr Mike Nevell has been a splendid guide to the world of industrial archaeology. Neil (now Sir Neil) Cossons and David Crossley were a great help when I was first getting interested in industrial archaeology and we all sat on the Ancient Monuments Advisory Committee of English Heritage. Happy days! Another more than helpful friend, who goes back a long time with me, is David Cranstone. David started life as a prehistorian with me at Fengate and is now a leading authority on industrial archaeology in general and salt mines in particular. He kindly gave me several useful hints and references.

At HarperCollins I am grateful to Martin Redfern, who took on Richard Johnson’s mantle, and to Ben Buchan, whose editorial comments have greatly strengthened this book. I am also deeply indebted to Rex Nicholls who drew the line drawings and to the book’s designer. Special thanks too to Sophie Goulden, Ben Buchan, Richard Collins and Geraldine Beare.

I am also grateful to family members who provided me with unexpected information on various topics: Roderick Luis (Crimean War huts) and Nigel Smith (navvies in the North Pennines). Nigel, a bookseller by profession, found me articles and out-of-print books and his elder sister, my wife Maisie, organised my photographic expeditions and managed to sort out the mystery of the two Causey Arches – an example, incidentally, of how the internet can waste time and lead one astray. Heaven alone knows how she has put up with my moods during this four-book marathon. Finally, and despite the best efforts of all of the above, any errors that remain are mine alone.

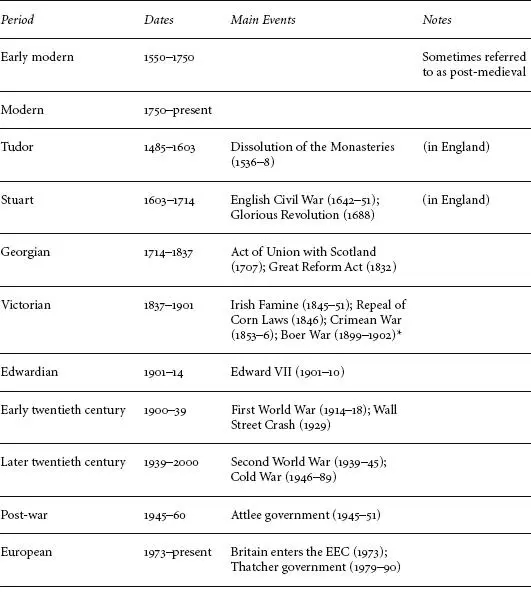

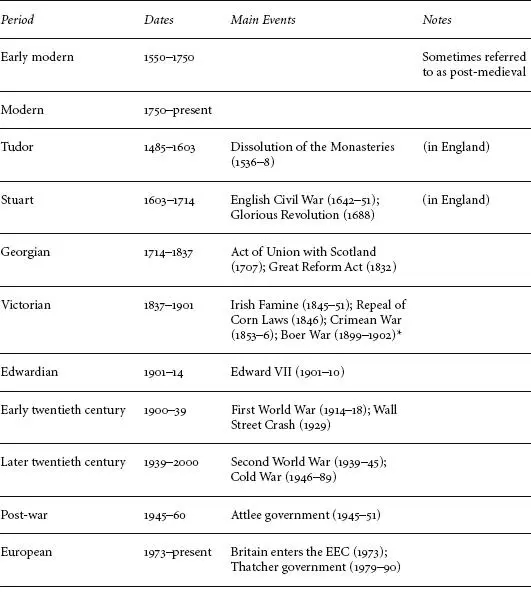

Dates and Periods

* Strictly speaking this should refer to the Second Boer War. The First Boer War (1880-81) was more a skirmish, which the Boers won.

IntroductionArchaeology and Modern Times

BEFORE I GET involved with the ‘meat’ of the book I’d first like to say a few words on the nature of modern historical archaeology in Britain, which is probably the fastest growing branch of the subject. When I started my professional life my team worked with the Peterborough New Town Development Corporation clearing land for factory building. That was back in the early 1970s, long before television programmes like Time Team had managed to convince the public at large that there was such a thing as British archaeology. Too often we would arrive at a site and announce that we’d come to survey and excavate, only to be greeted with incredulous stares and humorous comments to the effect that surely we would be better employed in Egypt, Greece or Italy. Then, when I had shown the builders (and anyone else who happened to be hanging around on site) the air photographs with the ring-ditch evidence for Bronze Age barrows and explained that these were as old as Stonehenge – which in turn was much older than the Parthenon or King Tutankhamun – the scoffing would cease and most of my audience would become our enthusiastic supporters. Sometimes their enthusiasm was such that it was hard to get much work done.

But just suppose for one moment that we had arrived on site and announced that we were planning to survey and excavate the ramshackle nineteenth- and early twentieth-century farm buildings that were then such a common feature of the city’s eastern fringes. In actual fact, those buildings were rather important, as the Fens, which were drained in the seventeenth century, were once a major producer of food for Britain’s rapidly expanding urban populations. But I very much doubt whether we would have found it quite so straightforward to silence the scoffing, because even in the better-informed times we currently live in, many people suppose that the terms ‘archaeology’ and ‘modern’ are mutually exclusive.

It’s not unreasonable to assume that a fair amount of time needs to pass before archaeological research becomes possible, let alone desirable, or informative. But, actually, this view is wrong because archaeology is not just about excavation; it’s an approach to the past that can be equally relevant when applied to something as young as a month, or as old as a millennium. Just imagine, for example, that an entire townscape is bombed flat, as happened in Coventry or in large parts of east London. In those cases archaeology is almost the only way to resurrect in any meaningful way what enemy aeroplanes destroyed. Under such circumstances, old pictures and sketches can, of course, be useful, but accurate measurements, made then and there on the ground, will be needed if reconstruction is to be attempted. In postwar years town centre developers did as much damage to Britain’s historic towns and cities as Nazi aircraft, and almost as quickly. Today this would not happen, but in the fifties and sixties pre-development surveys rarely took place. So such peacetime destruction was often horribly complete.

Читать дальше