At my feet – far from an easy toddle down a few amenably angled rocks – was a vertical step of about three metres. Its bottom was a little platform of rock, on either side of which the mountain fell away with fatal steepness. To get to it required a down-climb as if on a very steeply raked ladder, only with tilted footholds of wet rock instead of rungs, with no guarantees of integrity and no margin for error at the bottom. Piece of cake.

I pulled out the map and looked at it helplessly. I’d no phone reception, and no rope – ropes are not necessary to reach the top of all but a few major mountain summits in Britain, *and next to useless unless you have someone with you. This was the way off; the only other option was to go back the way I came, and I didn’t fancy that either. With increasing alarm, I looked around at the clouds and tried to rationalise. The down-climb in front of me looked delicate, but achievable. I must have done it before, though probably under direction and encouragement – and with even a helping hand – from Tom. But I had done it. And confidence was two-thirds of the battle. As long as I didn’t lose my cool I could do it. Just a few feet of down-climbing and a bit of exposure, and I could be on my way to a meal and a bed. Either that, or I’d just have to learn to live up here.

Descents like this are what fatal-accident statistics are made of. Coming down mountains claims more people than going up by a ratio of about 3 to 1. What was worse, I really hadn’t expected this. By ploughing up the hill, waving my previous experience of the mountain as a tool which, as we’ve seen, turned out to be less than reliable, I’d neglected to do enough research. A failure. But a lesson, too – and one I could learn from provided I could safely find a way out of this jam.

Mustering confidence, I fixed my mind on something random. I’d read somewhere that reciting your telephone number backwards during times of fear engaged a part of the brain that antagonistically quelled your fright cells; as I turned to face the rock and placed my foot on the first ledge a few feet down the crack, I shakily began to do it. Three points of contact at all times; look after your hands, and your feet will look after themselves. I could smell the murk of the rock as I pushed my face close to it, trying hard to make my entire world the crack before me and the narrow tube of rock at my feet I had to get down. No mountain, no drop – just this little ladder. Nothing else.

Concentrating on moving my hands to where my feet were, striking the rocks with the edge of my fist to check their stability, and mumbling my reverse phone number aloud with my exhales, I steadily made progress down the crack. I dropped down the last foot, landing squarely on the little platform. My heart audible in my ears, I took a deep breath and continued on down the ridge, not wanting to lose momentum until these dangers were passed.

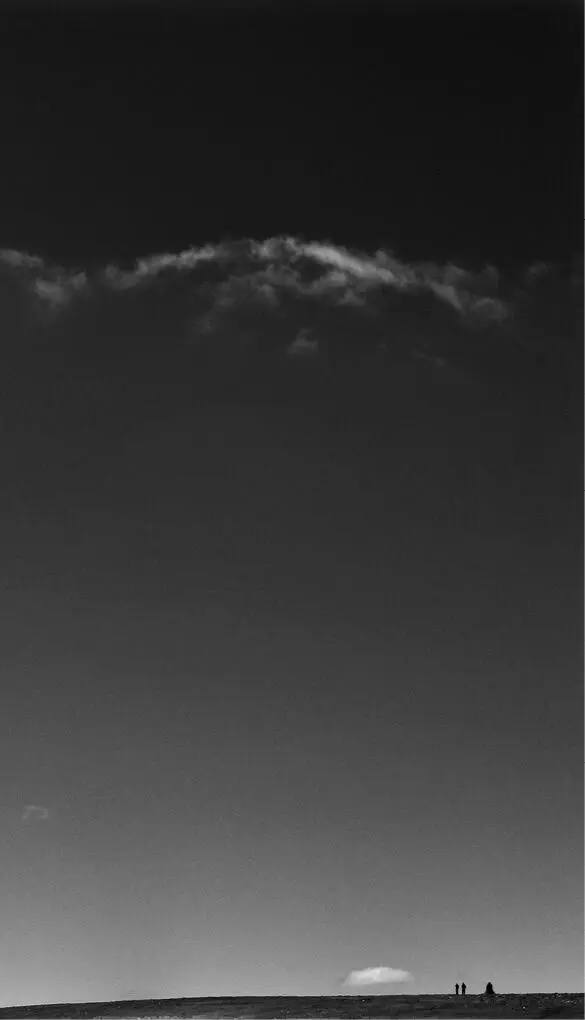

I rejected the crest of the precarious rocky sail in favour of the lower grassy terrace, moving to the right of the ridge’s frightening-looking apex. Trying to move as smoothly as I could, I traced the skinny path with my eyes then followed it with my feet, taking care – great care – not to trip. Writhing cloud had now clogged the void to the right, momentarily taking away the psychological impact of the drop. It parted as I approached the end, and I caught the glint of the river far below and the edge of Beinn Dearg’s mighty south-west buttress. There it was: that memory, that feeling of height – the kind of feeling that hits you like a nine-iron to the back of the legs. It was exactly what I didn’t need at that precise moment, but I stayed focused for the last few feet of the traverse. Then suddenly it was over. I scrabbled over a few rocks onto a little ledge, and when I saw that the mountain was considerably tamer from here on and that there were no more surprises in store, I let out an audible groan of relief, crumpling against the rock, my legs buzzing, arms shaking, breathing rapidly. That had been unexpectedly hairy.

Although I wasn’t off yet and the descent was still going to be difficult, I now knew that I was going to get down. After that, dinner was going to taste particularly good. I might even have an extra beer to celebrate being able to have an extra beer.

But this was only the first. As it would go, fifteen more mountains lay ahead – each with its own challenge, its own particular conditions, feel and story to tell. Beinn Dearg wasn’t the hardest. It also wasn’t the highest. But for me this was the mountain I’d always associate with this feeling of height ; of that elevated perspective you can only get from a mountain, and of the exhilaration and the fear that grips you by the stomach – the basic elements that make these places so special. In 1911 the Scottish-American naturalist John Muir wrote that ‘Nature, as a poet … becomes more and more visible the farther and higher we go; for the mountains are fountains: beginning places, however related to sources beyond mortal ken.’

I rose, and as I did so I pushed my wet hair out of my face and felt a substantial deposit of sharp sandstone grit upon my forehead. Confused for a moment, I realised my hands had picked it up off the rock and I’d wiped it onto my brow every time I’d mopped it. I was literally sweating grit.

My eyes followed the rock at my feet up towards the ridge I’d just climbed. The stuff I was carrying down the mountain on my forehead, these mountains are made of it. That brown, course-grained sandstone is even named after the area best exhibiting it: Torridonian sandstone, they call it. The whole range has rocks made of this grit as their bedrock. It’s why Beinn Dearg is called Beinn Dearg: for the way the sun lights the brown sandstone and deepens it to red in the westerly glow of sunset. It’s famous for this.

But nobody ever tells you about the lichen. Brilliant white whorls of it, augmenting almost every rock. Unless you were on the hill you wouldn’t see it or know it was here. But up on the ridge it’s everywhere. It looks as if the mountain is pinned with white rosettes; silly little patches of prettiness adorning its hard skin.

*Which was of course said by ill-fated climber George Mallory at a lecture in 1923 when asked, ‘Why climb Everest?’ Nobody really knows what he meant, or even if he said exactly this; it could have been something profound, or it might simply have been irritation at the question. Either way, it has passed into history as the most famous three-word justification of the ostensibly pointless.

*Most famously, Sgùrr Dearg’s notorious ‘Inaccessible Pinnacle’ on the Isle of Skye. There are other summits in Britain – indeed, more on Skye – that require the use of a rope, and ability is of course subjective, but there are ways up most of our principal mountains without additional aid, certainly in summer.

PART I

SPRING

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.