Sadly, the first recorded automotive road fatality in the UK was also in 1896, when Bridget Driscoll, 44, was killed in the grounds of the Crystal Palace on 17 August. She was walking with her 16-year-old daughter, May, and a friend when she was run over by a Roger-Benz car being driven by Arthur Edsall. At the inquest, Florence Ashmore, a domestic servant, gave evidence that the car went at a ‘tremendous pace’, like a fire engine – ‘as fast as a good horse could gallop’.

The driver, working for the Anglo-French Motor Co., who were part of an automotive exhibition taking place at the Crystal Palace, said that he was doing 4mph when he killed Mrs Driscoll and that he had rung his bell and shouted ‘Stand Back!’ as he approached. However, it was suggested that Mrs Driscoll seemed bewildered in front of the car. She may not have interacted this closely with a motor vehicle before. Who knows? There were then fewer than twenty in the whole of the UK and the public were certainly not educated in how to cross roads safely. Edsall had been driving for only three weeks at the time, and as no licence was required, the fact that he apparently had not been told which side of the road he needed to travel on was overlooked … The case went to court, but with conflicting evidence about the speed and manner of Mr Edsall’s driving, the jury returned an accidental death verdict. Interestingly, there was no outrage in the newspapers at the time, just a sense that it was an unfortunate accident. It would be some years before the press became powerful enough to express outrage in the way that we take for granted today. It’s also worth noting that, although people had been killed by horses or carriages for many years, high-profile autocar accidents did start to bring up some public discussion of these dangerous new machines, which were loved by those who had them and often feared by those unfamiliar with them. For that reason accidents were reported perhaps a trifle more vociferously than they would have been if someone had simply fallen off a horse and broken their neck. It was, after all, the start of the unknown.

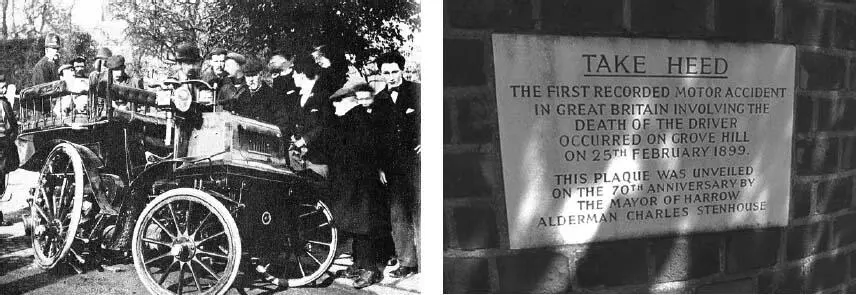

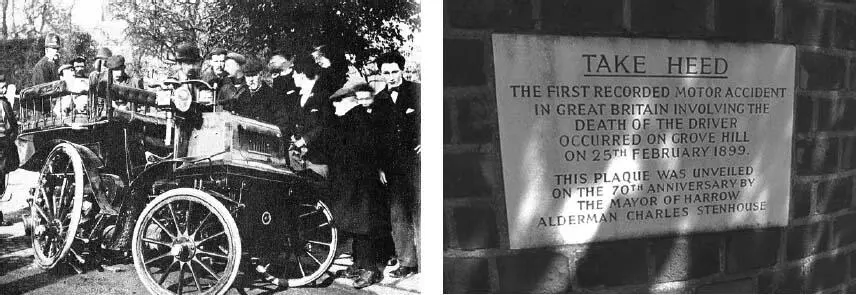

Perhaps ironically, the first death in an autocar accident was during an incident with an International Co. electric vehicle on 12 February 1898, when Mr Henry Lindfield of Brighton tried to stop his vehicle in order that his passenger, his 19-year-old son Bernard, could retrieve his bag, which had fallen off as they descended the hill off Purley Corner, in Croydon. When the brakes were applied the vehicle began to weave, before eventually hitting a post and then a tree, sandwiching poor Henry between the carriage and the tree. Son Bernard was thrown over his father and survived with relatively minor injuries, but, sadly, his father died in hospital the following day. Just over a year later the first fatal accident involving the driver of a petrol motor vehicle was recorded; 31-year-old engineer Edwin Sewell’s 6HP Daimler Wagonette crashed into a wall after a rear wheel collapsed following a rim breakage when the brakes were applied too harshly while descending a steep hill at speed. He died almost instantaneously. At the time he was demonstrating the vehicle to three passengers who were assessing it for possible purchase by their company, the Army and Navy Stores, then a well-known department store. The front-seat passenger, 63-year-old Major James Stanley Richer, was thrown clear of the vehicle with Sewell and suffered such serious injuries that he died three days later in hospital. The other two passengers were injured but survived.

The roadside plaque (unveiled on 25 February 1969) records the site of Britain’s first fatal road accident, on 25 February 1899.

As a result, the UK police started to take cars seriously, and the weight of public pressure – and in some cases outrage – meant that they had to. As far as research can prove, it was the Met that led the way, acquiring a Léon Bollée Voiturette in 1896, or possibly early 1897. The arrival of the Bollée, as it was usually called, is important because it represented the moment when the British police moved from enforcing legislation on motorists to becoming motorists themselves. Quite what those early Met police pioneer drivers would think of today’s high-speed chases on the M25 we shall never know, but to modern eyes the pioneering car does seem almost laughably poor in both performance and engineering terms. At that time the template for what makes an acceptable usable car, as opposed to an experiment down a dead-end avenue of design, was yet to be set, and the Mercedes-badged Daimler that made every other autocar old-fashioned overnight, and so set the car on its course to dominate transportation in developed nations by the early 1920s, would not appear until 1901.

1896 Léon Bollée Voiturette

The birth of the Léon-Bollée Voiturette light autocar goes back to the 1870s, when Amédée Bollée, son of a foundry owner specialising in bells, started making steam vehicles in Le Mans, France, way before the town became part of motor-racing folklore after Renault’s victory in the 1906 French Grand Prix there.

Although Amédée Bollée was a steam enthusiast, he could see the potential in gasoline-engined cars and helped both his sons, Amédée Junior and Léon, design and build them. Léon’s design was immediately successful, although I suspect anyone who ever crashed into anything while sitting on that front-mounted chair may have disagreed! The vehicle was considered fast in its day; even in their early days the police bought the fastest car they could afford, kicking off the arms race between the good and the bad guys earlier than most of us had realised!

Bollée’s design for a very short-wheelbased, 3-seater motor-tricycle, the Voiturette, weighed only 264lbs, used a tubular frame and featured a single back wheel, making it far more stable than having the single wheel at the front. The engine was an air-cooled, horizontal, single-cylinder unit of 650cc that was hung beside the back wheel on the near-side and used a large, heavy flywheel. It featured suction-opened inlet valves and mechanical exhaust valves with plain bronze bearings, hand-lubricated by grease for the main bearings and a splash-lubricated big-end. A tubular con-rod kept the weight down, while hot-tube ignition and a single-jet carburettor were so close to the float chamber that fires were common. The 3-speed transmission was by three virtually unlubricated gears on the end of the crank, which could be meshed with the three layshaft gears. The drive was by flat belt, a mechanism that was commonly used then to drive lathes and other machines in workshops. There was no actual clutch; the mechanical movement of the back wheel tightened or loosened the driving belt so that drive was achieved or neutral was obtained. Full-forward movement of the back wheel applied the belt rim to a stationary brake block. In some ways it was an elegantly simple solution; one fore and aft movement of the rear wheel achieved one of three outcomes. However, the Bollée was apparently quite tricky to actually drive, partly because it featured a small steering wheel on the driver’s right with a handle familiar to traction-engine drivers, which actuated an early rack-and-pinion steering system. Meanwhile, the left hand had to ease the gear stick gingerly back and forth to engage the drive or free it. Turning the spade grip at the top of this lever engaged a gear, and, in order to stop, the lever had to be hastily pulled backwards. I can’t imagine many of my former police colleagues (or myself, for that matter) taking it easily, but perhaps sheer fear would have engendered that on this device …

Читать дальше