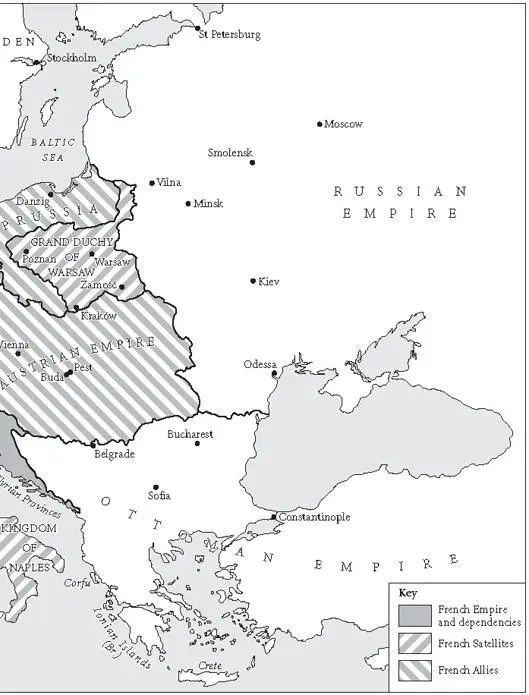

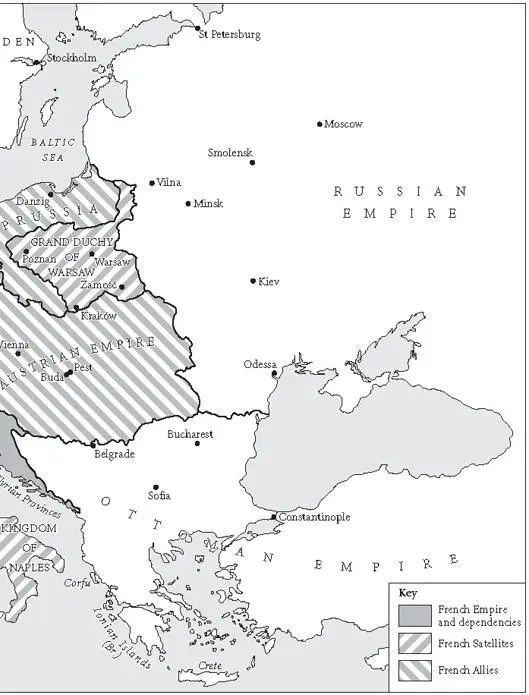

While there were many who resented this French stranglehold, others either welcomed or at least accepted it. The only open challenge Napoleon faced was from Britain, but while she was supreme on the seas, her only foothold on the Continent was in Spain, where General Wellington’s army was operating alongside Spanish regular and guerrilla forces opposed to the rule of Napoleon’s brother Joseph. But Britain was also engaged in a difficult and costly war with the United States of America, which restricted her military potential.

The disasters of the Russian campaign had changed all this, but not as profoundly as one might think. Although he was now at war with Russia and had lost an army trying to cow her into submission, Napoleon’s overall position had not altered. His system and his alliances were still in place, and the situation in Spain had actually improved, with the setbacks of the summer reversed and the British and Spanish forces under Wellington repulsed.

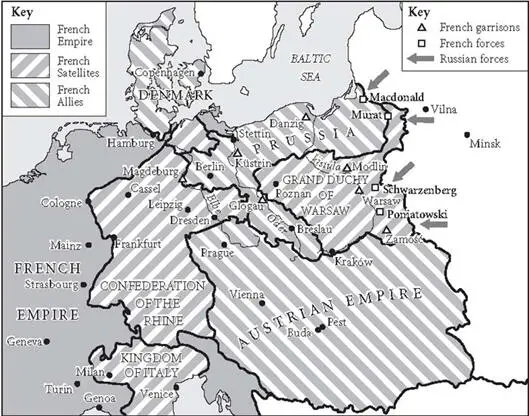

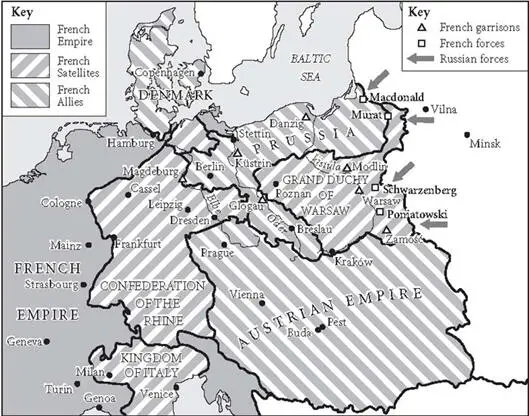

The only possible threat to his system at this stage could come from Germany, whose many rulers, beginning with Frederick William of Prussia, found his alliance increasingly onerous, and whose people burned with resentment of their French allies. But Prussia had been reduced to a minor power and bled economically by France over the past few years, while the other monarchs were too weak and too mistrustful of each other to present a credible challenge, and Austria was in no position to make war after her crushing defeat in 1809. Any who still dreamt of throwing off the French hegemony had to take into account the remains of the Grande Armée in Poland and a string of French garrisons in fortresses across Germany.

Napoleon’s self-confidence had not been seriously shaken by the events of 1812. He had blundered politically and militarily, and he had lost a fine army. But he knew – and so, despite the Russian propaganda, did most of the experienced commanders of Europe – that he had been victorious in battle throughout. ‘My losses are substantial, but the enemy can take no credit for them,’ as he put it in a letter to the King of Denmark. And he could always raise a new army. 4

France was still the most powerful state on the Continent. Russia had no comparable reserves of power or wealth, and had suffered greatly from the devastations of war in the previous year. With the benefit of hindsight Napoleon’s reputation and the basis of his power had been damaged beyond repair, but at the time it was clear to all that his position remained unassailable as long as he kept his nerve and consolidated his resources. And that is what he set about doing.

At Warsaw, on his way back to Paris, he had stopped just long enough to assure the Polish ministers that the situation was under control and that he would be back in the spring with a new army. At Dresden a few days later, he reassured his ally the King of Saxony and urged him to raise more troops. From there he also wrote to his father-in-law, the Emperor of Austria, saying that everything was under control and asking him to double the contingent of Austrian troops operating alongside the Grande Armée to 60,000. He also asked him to send an ambassador to Paris, so that they might communicate more easily. 5

On his return to Paris he set to work at rebuilding his forces. Before leaving he had given orders for the call-up of the age group which should have been liable to conscription in 1814, and this had yielded 140,000 young men who were already being put through their paces in depots. He also had at his disposal 100,000 men of the National Guard which he had set up as a home defence force before leaving for Russia. Mindful of the political situation in France, he now created a new force, the Gardes d’Honneur , made up from the young scions of aristocratic families and those opposed to his rule, drawn from the depths of the most royalist provinces. The improved situation in Spain allowed him to withdraw four Guard regiments, the mounted gendarmerie and some Polish cavalry from the peninsula. And he instructed his other allies in Germany to raise more troops to support him.

Europe at the end of 1812

Central Europe at the beginning of 1813

According to his calculations he still had 150,000 men holding the eastern wall of his imperium, with at least 60,000 under Murat at Vilna, 25,000 under Macdonald to the north, 30,000 Austrian allies to the south under Schwarzenberg, Poniatowski’s Polish corps and the remainder of the Saxon contingent under Reynier covering Warsaw, and over 25,000 men in reserve depots or fortresses from Danzig (Gdansk) on the Baltic down to Zamosc. He was therefore confident that he would be able to take the field in Germany with some 350,000 men in the spring. 6

But less than a week after his return to Paris, on Christmas Eve, bad news came in from Lithuania. As the remnants of the Grande Armée straggled into what they thought was the safe haven of Vilna, the men’s endurance had given way to the need for rest. Murat had failed to organise an adequate defence, and the advancing Russians were able to overrun the city with ease. The confusion and panic had prevented an orderly evacuation even by those units still capable of action, and a couple of days later not many more than 10,000 men crossed the river Niemen out of Russia. Napoleon was devastated by the news. He bitterly regretted having left Murat in charge, and dreaded the propaganda value of the event. But within a day or two he put it behind him, assuring Caulaincourt that it was an unimportant setback. 7

He was certainly not going to allow it to alter his plans or dent his confidence. The requested ambassador of Emperor Francis of Austria had arrived in Paris. He was General Count Ferdinand Bubna, a distinguished soldier whom Napoleon knew well and liked. In the course of their first interview, on the evening of 31 December, Bubna delivered an offer on the part of Austria to help negotiate a peace between France and Russia. Napoleon dismissed it.

He certainly wanted peace, probably more fervently than any of his enemies. He was forty-three years old. ‘I am growing heavy and too fat not to like rest, not to need it, not to regard the displacements and activity demanded by war as a great fatigue,’ he confessed to Caulaincourt. His only reason for making war on Russia in 1812 had been to oblige Tsar Alexander to enforce a blockade that he believed would bring Britain to the negotiating table. 8

With nothing better to do during their long drive from Lithuania to Paris, Napoleon had delivered himself, copiously and unstoppably, of his thoughts, occasionally pinching the cheek or pulling the ear of his travelling companion, as was his wont. Fortunately for posterity, Caulaincourt listened carefully and jotted down these ramblings whenever the Emperor fell into a doze or they stopped to change horses. Napoleon again and again asserted that he longed only for peace and stability in Europe, and that the other Continental powers were blind not to see that their real enemy was Britain, with her monopoly on maritime power and trade. Any peace that did not include Britain was of no value, and Britain was not prepared to envisage a peace on terms acceptable to France. She needed to be forced into compromise.

Читать дальше