If eating is an act of pleasure and cooking a celebration of ingredients and flavours, then surely the reward of cooking one meal a day from scratch is far greater than the effort involved in making it in the first place. Having children around me in the kitchen makes it unquestionably clear that we all have a better relationship with our food if in some way we are connected to what ends up on the plate in front of us – just being present in the kitchen watching, smelling and taking in the process of dinner being cooked is enough, but there is so much enjoyment to be had by actually getting stuck in.

Encouraging our children to enter the kitchen and feel their way around a recipe is so important, not just for them to develop their own tastes and interests but for society as a whole. Cooking should be an adventure, an exploration of ingredients and layering of flavours, a creative and intuitive act through which we express so much of ourselves – while I can at times be serious in the kitchen, the boys often serve to remind me that cooking is about fun. A kitchen should be a place where magic happens, and OK, sometimes the odd disaster too, but it shouldn’t be a place to fear, and good food shouldn’t be regarded as something for a special occasion or the weekend. Breakfast, lunch, dinner and all that comes in between are part of our every day – they all deserve to be gratifying.

REDISCOVERING GERMAN COOKING

I strongly disagree with the bad reputation that German food has overseas and outside its borders. I can’t help but feel that our ideas about the German diet are incredibly out-dated. Go back a few decades, especially to the 1950s, and it’s easy to see where today’s erroneous notions come from – back then life was very different.

A Fresswelle (wave of gluttony) swept through Germany in the 1950s – a backlash of over-eating brought about through the dietary constraints of wartime rationing and the very real feeling of hunger that still lingered in the minds of many. A booming economy, which not only raised the quality of life within the country but also stirred hopeful feelings among a nation who felt they had little to be proud of in the early post-war days, was reflected in the growing waistlines and body weight of the people. Indulgent eating symbolised a newfound freedom and happiness, which everyone was hungry for.

Germans adopted a bon vivant alter ego – that of the cocktail-swilling, chain-smoking gourmet. Exotic flavours and exciting new food items flooded the market. My mum remembers her parents bringing home a tin of Hershey’s syrup for the first time, acquired from the American army base; this was seen as the height of luxury and was enjoyed drizzled over everything. Many foodstuffs unattainable to most households due to their prohibitive prices in previous years became affordable to the masses, and thus things like butter came back into fashion and pushed out, thank goodness, cheaper alternatives like margarine.

This newfound passion for life didn’t just stop at the kitchen door. An Urlaubswelle (holiday wave) took hold of the nation too and carried many flocks of Germans in their socks and sandals abroad on holiday. No sunlounger was safe – I am laughing as I write this but it’s true: the competitive side of a German is fierce, and when out in large numbers they are a force to be reckoned with.

While this wave of travel gained the Germans their rather unfortunate sunlounger-hogging reputation, they also gained something wonderful: the taste for new flavours, and ideas from cuisines and lands other than their own. Newfound ingredients, probably recipes too, were brought back to many German kitchens and an experimental, lighter way of cooking and eating at home began to emerge.

During the 1960s and 70s this new wave of cooking was kept buoyant by the many people who came to settle in West Germany. The gastronomic influence was broad, with people arriving from northern Africa, Portugal, former Yugoslavia, Greece, Italy and Spain. Probably, though, the most prominent taste influence was Turkey – doner kebab shops started popping up on many street corners and soon became the snack of choice. Now, fifty years on, ask any German of my generation and they will tell you that the doner has been adopted by the Germans and become a ‘national snack’, a portable street food equally as popular as the Bratwurst .

The fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989 saw the reunification of Germany. While West German cuisine had flourished and evolved through outside influence over the past twenty-eight years, East Germany had been living under a communist regime where everything foreign was viewed with suspicion. In the East people had to make do with what they had, which meant that food was inextricably bound to the land and seasons. Armed with little more than what could be home-grown, a small selection of state-approved products and brands and an unlimited supply of vinegar, the cooking of East Germany was unfussy, recipes were pared back and methods uncomplicated. There was an unspoken awareness among the people that food was and should be seen as something more than just a meal. It was essential, yes, but it was also a hundred other things: bitter, symbolic, joyous, rich, poor, lucky, hateful, welcoming, precious, hopeful and everything in between.

When Germany reunited as a nation, food from all sides was brought together. Germany was one of the great melting pots of Europe, a place where so much existed side by side. The broad culinary and social diversity owing to a migrant population was evident through the rise and popularity of Italian, Greek and Turkish restaurants. Every taste was catered for, and perhaps because so many new ideas and flavours were filtering into each kitchen, the hunger for regional dishes, many that had been forgotten for a time, was also stronger than ever. Food that was directly connected to the surrounding landscape and to those families who had lived in it for many years was an important thing for people to cling on to as society changed. This is the food I grew up with – lost food, regional food, frugal food, seasonal food, exciting, new and brilliant German food.

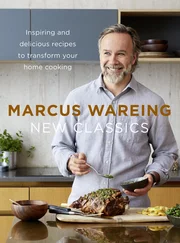

I use unrefined golden granulated sugar and golden caster sugar – they are more expensive than regular white granulated and caster but worth the extra pennies for the assurance that they have been less messed around with. I tend to err on the lighter side of sugar quantities in cakes and just generally, but feel free to add more to any of the recipes should it feel right to you.

I always use sea salt unless otherwise stated. If using flaky sea salt I scrunch it between my fingers before adding it to the other ingredients.

All eggs are free-range and medium in size unless otherwise stated.

I use unwaxed citrus fruit (easily found in most supermarkets these days), and I try to use organic as much as possible.

I cook with unsalted butter only. Salted for spreading.

All milk is organic whole milk unless otherwise stated. When possible I personally like to buy raw milk, but please do check health advice on this for yourself (and for your family).

We grow a lot of vegetables and soft fruit at our allotment; as a cook I feel it’s important to understand how our food grows. Tending this small plot of land over the last two years has made me have a new appreciation for the vegetables and fruit we eat, not to mention realise how undervalued much of what we buy from the shops is. I try to buy locally grown vegetables and fruit from markets and small shops as much as I can, but also do a weekly supermarket shop.

Читать дальше