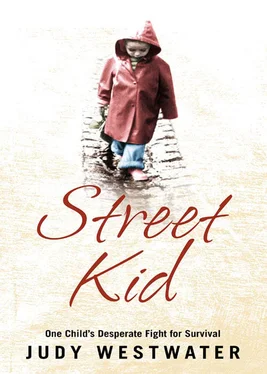

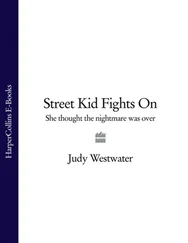

Street Kid

One Child’s Desperate Fight for Survival

JUDY WESTWATER

With Wanda Carter

FOR MY TREASURED FAMILY

My beloved children Jude, David, Carrie and Erin

and all my beautiful grandchildren

Cover

Title Page Street Kid One Child’s Desperate Fight for Survival JUDY WESTWATER With Wanda Carter

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Pegasus Children’s Trust

One Child by Torey Hayden

The Little Prisoner by Jane Elliott

Hannah’s Gift by Maria Housden

The Choice by Bernadette Bohan

Copyright

About the Publisher

W as two when Mum and Dad deserted us, leaving Mary, Dora, and me alone in the house for seven weeks without food, light or coal for the fire.

I was born in Cheshire in 1945 and although the war had ended that year, it had been a battleground in our house whenever my parents were together. When my dad wasn’t working in a factory he was dressed up in a herringbone tweed suit preaching at local spiritualist church gatherings. It was only when my mother married him that she realised what a nasty piece of work he really was but she still managed to have three kids with Dad before she decided she’d be better off with her Irish boyfriend, Paddy.

When Mum ran off she took with her our identity cards and allowance books. She must have thought that my father would see to it that Mary, Dora and I were fed and clothed but all he did when he realised he was saddled with us was ask our next door neighbour, Mrs Herring, to look in on us every so often and check we were okay. He said he’d be back the next weekend but he didn’t keep his promise.

So that was how the three of us came to be left in the house alone.

Mary was seven, and the oldest. I reckon that as soon as I was born, I knew better than to cry for my mother: it was always Mary who’d looked after me and Dora. Mrs Herring looked in on us now and then, letting us have whatever scraps she could spare; but it was Mary that kept us going. She must have longed for a mother’s care herself, especially when she had to go to school in such a terrible state. All the teachers were appalled that she was so dirty, and they’d often have her up in front of all the class to tell her off.

One day it got so bad for Mary that she dragged our tin bath into the living room, put it in front of the fireplace, and started filling it with cold water. She pulled me up from the hearth, where I was eating ashes, and said, ‘Come on, we’ve got to get you dressed. We’ve got to go and look for Mummy.’

We went out and made our way to the market, which wasn’t far from our house. It was cold; my feet were bare; and all the clothes hanging from the stalls were flapping in my face. I kept looking through them to see if I could see my mother.

And Mary kept saying, ‘Look for Mummy.’

After seven weeks, Mrs Herring was at the end of her tether. She had only meant to look out for us for a few days. She must have thought, ‘Where the heck is their father?’ Maybe Dad sent her messages saying he’d be back in a week or something. But the weeks went by and we were in a terrible state. In those days, times were tough but people looked out for each other, and I’m sure Mrs Herring just thought she was doing her best. But at some point she must have realized she had to do something or we’d get really sick. A bitter winter was setting in and we had no money for coal or food. When I touched my hair, I could feel it was all matted and crusty, and my body was covered in weeping sores that hurt when I lay down.

Mrs Herring contacted the welfare people, who managed to track down my father and served him with a summons. Dad suggested to them that he find someone to look after us in exchange for free lodging at our house, and they agreed with the plan. A homeless couple of drifters called the Epplestones came forward, and the welfare board was satisfied. In the years after the war they could barely keep up with the rising tide of poverty and need, so once our case was closed they didn’t bother their heads about us again.

After five months my mother returned home, pregnant and penniless. My dad allowed her back in the house on the understanding that she didn’t see Paddy again and had her baby adopted. She agreed.

I don’t remember being glad Mum was back or anything like that. You only feel glad or relieved if you have something to compare it with but life with her had always been pretty awful for us. Still, it was better than being in the care of Mrs Epplestone who’d hated having to look after us and shouted a lot. Most of the time, Mary, Dora and I had sat huddled like mice on the old brown couch in the living room, with its springs poking through the cover. But it was when it came to mealtimes that the horror really began. Bowls of porridge were banged down in front of us and when I couldn’t eat the nasty, slimy, lumpy stuff, Mrs Epplestone would yank my head back by the hair and force the spoon down my throat until I couldn’t breathe. When I choked and gagged she’d hit me across the face.

Mum had no intention of giving up her baby when it arrived and when my Dad discovered that she was keeping her he was furious and came straight over to the house. It was a frosty New Year’s Day and Paddy was round, warming himself in front of the fire. He must have come in for a quick one with my mother and to see the new baby. They both got a big shock when the door opened and there was my father. When he walked in and saw them playing happy families, and Paddy’s trousers over the chair – in his house – all hell broke loose. The men tore into each other like dogs. My mother was screaming like a banshee, and they were hammering into each other with their fists and breaking up the furniture.

Paddy was a big fellow, much larger than my father, and he’d been a boxer in the army, so he soon got the upper hand. Dad stood there, all bloody with his chest heaving, knowing he’d been beaten and yet burning up with fury and wanting to kill them both. Mum and Paddy looked back at him, confident now that my father had been beaten. My mum told him that they were keeping the baby and that there was nothing he could do about it.

Being told he couldn’t do anything made my dad determined to show that he was still boss in his own house. He strode across the room to where we were huddled, boiling with anger, and grabbed me. I hid my face against Mary’s chest and clung to her. She and Dora held on tight, screaming at him, ‘Leave her alone! Leave her alone!’ But they only managed to hang on to me for a few seconds before he peeled their arms away.

I don’t think I made much of a sound, but I can still hear Mary and Dora screaming my name as my father dragged me down the street. I can remember my legs not being able to touch the ground: they were just batting the air as Dad took great big strides to get away from the house. I didn’t know where we were going or what was going to happen. I’d just seen him fighting Paddy and was terrified that it might be my turn next. I don’t know how far I was dragged but it seemed like a long way. I didn’t have a coat and felt colder than I’d ever been in my life.

Читать дальше