‘Have your tea, then get out of my sight.’ She pushed a cheese triangle across the table at me.

Afterwards, I went and sat under the table, which was where I always hid when Freda was around. It had a long cloth, so no one could see I was there. I stayed quiet as a mouse until it was time to go up to bed.

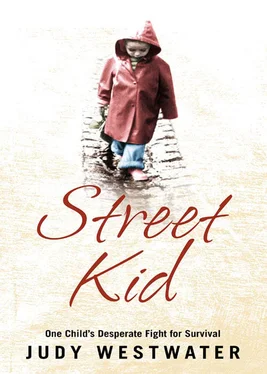

After that, Freda shut me outside in the yard every day. The first time it rained, I ran to the back door and tried to get in, but it was locked. I hadn’t known until then that Freda actually locked the door. By the time I’d made it to the privy I was soaked through. I had to shelter in the toilet most of the afternoon, which smelt damp and mouldy, like the cupboard under the sink, and I felt I’d never get warm again.

One day, when it was just starting to spit with rain, our neighbour, Mrs Craddock came out of her house and looked over the wall.

‘All by yourself, chicken?’ She tutted and cooed, coaxing me over. I approached her cautiously. Mrs Craddock had rollers in her hair and was wearing a flowery pink overall, stretched tight across her enormous bosom.

‘Come inside and keep warm.’ She scooped me up, lifted me over the dividing wall and put me down in her yard. I saw she was wearing brown tweed slippers with pompoms on them.

‘Let’s get you warmed up then.’

She took me by the hand, led me indoors, and sat me down on the sofa by a big fireguard that had washing hanging over it. I was very frightened. I’d been told to stay in the yard.

Mrs Craddock stood at the window watching for Freda, hands on hips, and as soon as she saw her get off the bus she opened the front door. I tried to slip past her but she pushed me back, tucking me behind her, protectively.

I was panicking badly now. I’m going to be in big trouble. Freda’s going to go mad.

But Mrs Craddock was puffed up with rage and nothing was going to stop her now. She didn’t pause to think that I’d be the one getting hurt at the end of it.

‘Oi Freda! What do you bloody think you’re doing leaving this child in the yard? It was raining for Christ’s sake!’

‘What the hell’s she doing there? Give her back here! And you can take your fat nose out of my bloody business.’ Freda’s face looked sharp and pointy as a knife and I thought she was going to go for Mrs Craddock.

‘You stupid cow! I don’t know how you can stand there. People like you should never be allowed to have kids!’

They went at it hammer and tongs, watched by some of the women from neighbouring houses. Finally, Freda grabbed me and took me with her, slamming the door behind her. She dragged me through the shop and down the steps into the room at the back. I thought she’d beat me senseless, but instead she gave me a couple of slaps and sent me to bed. I think the row with Mrs Craddock had exhausted her. Mrs Craddock never took me in again. But from then on, other people began looking out for me, and occasionally they threw toys over the wall.

One day, there was a thunderstorm and I was feeling frightened. A girl came running over to me. She wasn’t wearing a coat and was getting drenched. She looked about eight or nine and had ringlets, which the rain had plastered against her head.

‘My mum said to come and fetch you.’

She lifted me over the wall and we ran, hand in hand, through the sheets of rain to her house. Her mum was waiting at the door.

‘You poor little thing. You come in and get dry.’ She led me into the kitchen and dried me with a towel, fussing over me as she did so.

‘I’ll make you a cup of cocoa. That’ll warm you up. What’s your name, poppet?’ She was talking to me soothingly as she put some milk and water on the hob.

‘Judy,’ I whispered.

‘And how old are you?’

‘Three and a half.’

‘Now poppet, I think you’ll get warmer if you come into the living room and sit by the fire.’ She led the way to the other room, where her two daughters and husband were sitting.

‘Tony, this is Judy. She got all wet in the storm,’ she said.

‘Hello young lady. How would you like to come sit by the fire with me and help me win the pools?’ With that, he scooped me onto his knee and let me help him pick out the winning teams with a pin on his football coupon.

It was the first time I’d ever got a glimpse of what family life could be. I bathed in the warmth of it.

F reda never gave me anything to eat or drink in the mornings. Whenever I got thirsty, I’d scoop water from the toilet; but there was nothing I could do to calm the gnawing hunger I felt every day.

It wasn’t long before I made my escape from the yard. One day I stood on tiptoe to reach the bolt on the back gate. I pulled on it with all my strength and when it slid back it cut my hand. But it didn’t matter to me that it was bleeding because I’d got out. The only worry I had was that now I’d opened the door, I couldn’t close it from the other side. But a second later I managed to slip the toe of my sandal underneath and closed it. I felt very proud of myself.

On the other side of the gate I was faced with a high stone wall with a path running along in front of it leading to a small green square with rows of houses backing onto it. As I stood there on the grass, a boy came up to me. He must have been about twelve.

‘You alright? Are you lost or something?’ I didn’t answer, didn’t run away either. I just stood there. Then he went away.

From time to time I noticed women coming out of their back doors carrying bags of rubbish over to the low, open-topped bins at each corner of the square. My tummy hurt from hunger and so, as soon as the women were gone, I went over to one of the bins, stood on a brick, and leaned in to hunt for scraps.

The smell was almost overpowering, but I delved down into the damp and greasy rubbish, rummaging through it looking for something edible. I found a promising looking newspaper parcel and unfolded it. Inside there was a handful of potato peelings and some chicken bones. I picked up a bone and sucked on it, tearing off a few tiny strands of meat with my teeth. It tasted good, but didn’t satisfy my hunger one bit, so I started on the peelings. They didn’t taste nice at all. After eating as many of them as I could stomach, I leaned further over the bin and dug down deeper, looking for other newspaper parcels. I spotted one, and pulled it loose. It contained an old crust of bread and some bacon rind, which I eagerly devoured.

That first time I ventured out of the yard, I didn’t go any further than the square behind our houses, but it wasn’t long before I was exploring the rest of the neighbourhood. I wandered down the gutters and cobbled alleyways that ran between the rows and rows of back-to-back brick houses. None of them had front gardens or yards and, without a flowerbed or patch of grass to bring colour to the streets, Patricroft was a monotonous place of grey stone and sooty brick. The only things that brought colour to the place were the barges which shipped their cargo along the old canal. I’d stand on the iron bridge and watch them for hours as they made their slow progress through the tar-coloured water, littered with bottles and other bits of rubbish. If anyone came towards me I’d run away and hide.

One day, about three months after we’d moved to Patricroft, and soon after I’d first escaped from the yard, I walked past a gate, through which I could see some grass. Thinking it must be the entrance to a park, I pushed open the gate and went in. I found myself in a large garden, with beds of beautiful flowers planted in patterns. I’d never seen anything so wonderful in my life, and wandered through the garden in the sunshine, hardly aware of time.

Читать дальше