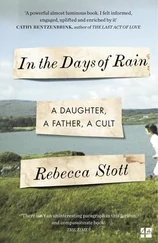

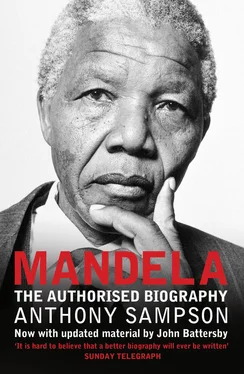

Mandela never forgot that Sidelsky, as he has written, was ‘the first white man who treated me as a human being’, the man who ‘trained me to serve our country’. A few years later, when Mandela was briefly prosperous and was driving an Oldsmobile, he noticed Sidelsky, who had fallen on hard times, waiting at a bus stop, and gave him a lift home. Sidelsky was puzzled that Mandela would go no further than the kitchen; and the next day Mandela sent him a cheque repaying the £50. Forty years later Sidelsky and his daughter visited Mandela in prison, and joked about his advice to keep out of politics: ‘You didn’t listen, and look where you ended up!’ 14

But politics were all around him. He shared an office with a young white lawyer named Nat Bregman, a cousin of Sidelsky, a ‘light-hearted communist’, as he later called himself. Bregman, a part-time stage comedian, enjoyed Mandela’s company, finding him reserved but with a good sense of humour. 15He took Mandela to communist lectures and to multi-racial parties where he met friendly white left-wingers, including the young communist writer Michael Harmel. Mandela was amazed by Harmel’s combination of intelligence and simple living – he refused to wear a tie – and later he would become a close friend.

In the law office Sidelsky warned Mandela against a black communist, Gaur Radebe, who worked in the firm. A flamboyant, strongly-built man ten years older than Mandela, Radebe spoke five languages, and was helping to set up the new African Mineworkers’ Union. 16He did not conceal his militant views in the office. ‘Keep away from Gaur,’ said one colleague. ‘He will poison your mind. Every day he sits on that desk planning a world revolution.’ But Radebe befriended Mandela, and told his white bosses he was really a chief: ‘You people came all the way from Europe, took our land and enslaved us. Look now, there you sit like a lord while my chief runs around on errands. One day we will catch all of you and dump you into the sea!’ Mandela was dazzled by the coolness and confidence with which Radebe argued with whites. 17Radebe urged him to join the communists, but Mandela was working too hard in the evenings for his law examinations. Twenty years later the two men had almost reversed their positions: Radebe, after being expelled from the Communist Party in 1942 for money-lending activities, joined the anti-communist Pan Africanist Congress, while Mandela defended the communists within the ANC. 18

Mandela was now living in the midst of a black slum, lodging with a minister, the Reverend Mabutho, at 46 Eighth Avenue, Alexandra, a chaotic township six miles north of the city with no electricity, called ‘the Dark City’. Alexandra was a jumble of brick houses and makeshift shacks overflowing with the wartime influx of workers from the countryside. It was insanitary and noisy with hungry dogs – a total contrast to the secluded white mansions beyond its fence. But Alexandra had a village vitality and a sense of community which they lacked. It was ‘a cauldron of black aspirations and talent, and a mirror of black frustrations’, wrote the activist Michael Dingake. 19Alexandra mixed up the tribal Xhosas, Zulus and Sothos in the scramble for urban survival, and Mandela was surprised to find himself pursuing a Swazi girl. He became more interested in other tribes, learning about the Zulus’ past glories from a property-owner called John Mngoma, who told him long stories about the heroism of the Zulu King Shaka and described events which never appeared in the whites’ history books. 20

In Alexandra, Mandela was among the poorest, sometimes having to walk twelve miles a day to save the bus-fare to and from the office in the centre of town. He remembers feeling humiliated when girls noticed his shabby clothes, and was envious of the more glamorous young ‘Americans’, the dandies in sharp suits with wide hats and flashy watches, often stolen, who attracted women; but he maintained his more staid English style. 21He was helped by friends who lodged in the same house: later he felt guilty that ‘not once did I think of returning their kindness’. 22

Mandela soon found his feet as an urban African, able to fend for himself. He no longer needed the support of his father-figure the Regent, who was now very frail. The Regent visited him in late 1941, and did not reprove Mandela for his past disobedience; six months later, when the old man died, Mandela went to his funeral in the Transkei, and regretted that he had not been more grateful for the Regent’s past kindness. He also wished he had taken the opportunity to ask him about white supremacy and the liberation movement. 23By now he had outgrown his purely Xhosa perspectives, but he was still torn between his tribal obligations and the opportunities offered by the big city.

Mandela completed his BA degree through a correspondence course, but soon realised it was not the key to success: ‘Hardly anything I had learned at university seemed relevant in my new environment.’ He returned to Fort Hare to receive his degree, wearing a new suit bought with a loan from Sisulu. His nephew Kaiser Matanzima, now preparing to be a chief, urged him to return as a lawyer to the Transkei, but Mandela was becoming more interested in the national stage.

He soon moved out of Alexandra. To save money he lived for a short spell in the mining compound of Wenela (Witwatersrand Native Labour Association), which provided special quarters for visiting chiefs; there he met tribal dignitaries, including the Queen Regent of Basutoland. Then he moved to Orlando (now part of Soweto), a municipal suburb twelve miles outside Johannesburg which had been planned in 1930 as a model township for ‘the better class of native’. Orlando stretched out across open farmland, overshadowed by the giant towers of a power station, a vista of two-roomed houses without floors or ceilings between bumpy dirt tracks. It was more hygienic but less intimate than Alexandra: Mandela liked to say that in Alexandra he had no house, but a home, while in Orlando he had a house without a home. But he was now close to Walter Sisulu, who lived with his mother in a house noisy with politics; and Orlando was destined to set the pace for all black South Africa.

Mandela still had to study – this time for a law degree. Early in 1943 he enrolled at the University of Witwatersrand, which stood, with its imposing columns, on a hill north of Johannesburg. ‘Wits’, unlike the Afrikaans universities, admitted a handful of black students to study alongside whites, though they could not use the sports fields, tennis courts or swimming pool. Some white lecturers strongly disapproved of black students, including Professor Hahlo, a German-Jewish lawyer who regarded law as a social science for which blacks and women lacked the mental discipline and experience. 24But other law lecturers, like Julius Lewin and Rex Welsh, were generous liberals, and many of the white students had returned from the war with a hatred of racism. Among them were several communists, including Joe Slovo and his wife Ruth First, Tony O’Dowd and Harold Wolpe. Ruth First, who was later to be a close friend and colleague, remembered Mandela as ‘good-looking, very proud, very dignified, very prickly, rather sensitive, perhaps even arrogant. But of course he was exposed to all the humiliations.’ 25Joe Slovo had the impression of ‘a very proud, self-contained black man, who was very conscious of his blackness’ and very sensitive to the perception that ‘when you work with a white man, he dominates’. 26Ismail Meer, who was Ruth’s close friend, found Mandela ‘fairly unsure of himself’ and detached from student politics: ‘He was the best-dressed student, and he was not going to get involved readily in the political activities at the campus. He was very cautious.’ 27Mandela ‘had a friendly dignity about him’, recalled another contemporary, Nathan Lochoff: ‘a little shy, not assertive in any way’.

Читать дальше

![Мик Уолл - Когда титаны ступали по Земле - биография Led Zeppelin[When Giants Walked the Earth - A Biography of Led Zeppelin]](/books/79443/mik-uoll-kogda-titany-stupali-po-zemle-biografiya-thumb.webp)