The true astronomical arrangement of the stones would have been appreciated sooner had there not been an almost universal preoccupation with plans of the monument, that is, with charts in only two dimensions. To understand the acumen of its builders one must study its three-dimensional form—a hard lesson that we are taught by the long barrows and timber circles. Another obstacle to progress has been an obsession with the idea that sightings from prehistoric stone circles were usually made towards points on distant horizons. The horizon is all-important, of course, but the people of the Neolithic and Bronze Ages will prove to have been in the habit of creating artificial horizons, just as surely as astronomers and surveyors today use something of the sort in their levels and theodolites, albeit for quite different reasons. Such reference planes were created long before the time of Stonehenge—in the first place, no doubt, to remove the irregularities of a tree-covered horizon. They were incorporated into the Stonehenge monument in several different ways, and the alignments of the stones there will be properly understood only if they are systematically taken into account.

Addressed as it is to a general rather than a professional audience, this book includes only the barest details of the underlying calculations, but those who wish to repeat them should be able to do so—with the help, if needed, of the appendices. There is not a single result in it that might not be made more precise after closer study and field work, but there is a law of diminishing returns in these matters and I believe that the main drift of the argument will survive such improvement. The analysis of prehistoric astronomical alignments demands accurate data, and the Stonehenge archaeological record is not in the best of shape. I have drawn heavily on the field work of archaeologists who are likely to feel uneasy at the use to which their work is being put. They inhabit an earth-bound world that makes them uncomfortable with lines of geometrical straightness, and it is not surprising that they have often omitted to record precisely the information needed here. The real cause for surprise is that they have so often recorded what was needed, and my debt to their recording is almost total. Many will be horrified at my defence of Alexander Thom’s Megalithic Yard (0.829 m), and even more so by its occasional use in plans. By this I do not mean to prejudge the question of whether it was in use, but merely to simplify the task of judging whether it might have been so. Of one historical truth one may be quite certain, when adding a scale to one’s plan: the metre was not in use in the Neolithic period.

The interpretations offered here do not lend themselves to exactness, and it is all too easy to quote results to a nonsensical degree of accuracy that might suggest otherwise. There are writers who publish declinations and directions that by implication are accurate to a thousandth of a degree, but who have not even taken astronomical altitude into account, although it would have displaced their findings by angles of the order of a degree, twice the diameter of the Sun. There have been archaeologists who have considered that they have done their duty by the points of the compass if they have marked them on their plans to within five or six degrees. Those who repeat the threadbare story of Mrs Maud Cunnington, who is said to have made some of her measurements with an umbrella, should compare her azimuths with their own. A good umbrella is far better fitted to the accurate measurement of length than is a pocket compass to the accurate measurement of direction.

The many different sorts of monument to be considered were first and foremost religious centres, or at least focal points of religion, built by people in whose spiritual lives the stars, Sun, and Moon played an important role, perhaps even a central role. There are limits to what an insight into past observational practice can reveal about prehistoric religion, its symbolism and ritual, but one should not be unduly apologetic about its genuinely scientific nature. The activities reconstructed here were rule-directed, scientific in a very real sense, and their implications for human history, intellectual and practical, are anything but trivial. Here, for instance, we can dimly perceive the beginnings of mathematical astronomy, the oldest of the exact sciences, not to mention the roots of a geometry of proportion—which was destined to have an important place in ancient Greek philosophy and science. As a window into the beliefs of the past, this all surely deserves at least as much attention as a showcase of flint scrapers.

* * *

My debts are numerous. I was very fortunate to have Bill Swainson cast an editor’s eagle eye over my script. To the late A. G. Drachmann I owe the idea of self-denial in the matter of footnotes. I have weakened only occasionally—but then at some length—when adding asides that might have stood in the way of the main argument. Appendices and Bibliography are included at the end. (Those unaware of the distinction between dates BC and bc, for example, might consult Appendix 1. A few readers might want the basic astronomy in Appendix 2.) I should never have turned in the direction of Stonehenge in the first place without the encouragement of Francis Maddison thirty years ago, and his broad view of archaeology has certainly coloured my own. Richard North passed a critical eye over my Scandinavian asides. Above all I owe a debt to an entire profession that is not really mine, and especially to Tjalling Waterbolk for his expert comment, on the continental material in particular. The book’s dedication, however, can only be to my wife Marion for her unstinting support. And to her patience, not even Chaucer’s Clerk could have done justice.

J. D. N.

July 1996

A few typographical corrections to the first printing have been made here, together with some minor adjustments to the star maps of Figs. 4and 210. That the corrections called for were not more numerous I owe largely to the care of my editor Toby Mundy. My indebtedness to him has accumulated steadily since he first took the book in hand.

J. D. N.

November 1996

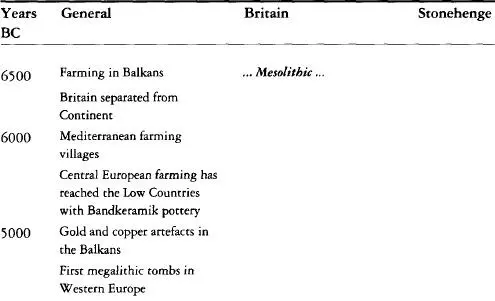

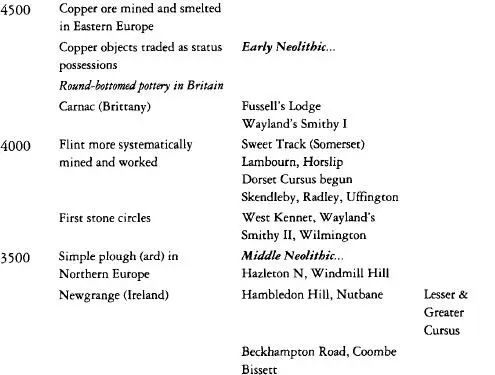

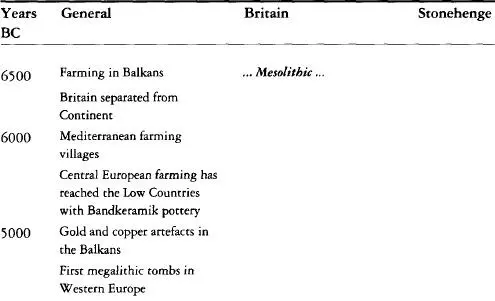

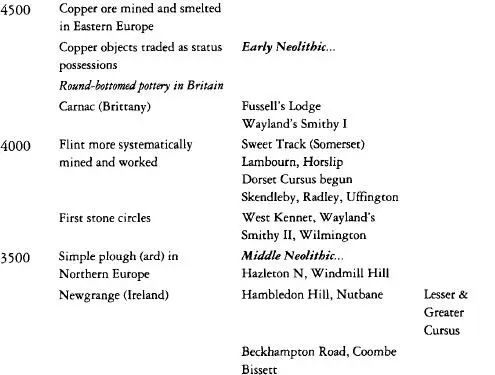

CHRONOLOGY

1

INTRODUCTION

… the Discovery whereof I doe here attempt (for want of written Record) to work-out and restore after a kind of Algebraical method, by comparing those that I have seen one with another; and reducing them to a kind of Aequation: so (being but an ill Orator my selfe) to make the Stones give Evidence for themselves.

John Aubrey, Monumenta Britannica , ed. J. Fowles and R. Legg (1980), p. 32

The People

MOST of the achievements recorded in this book were those of people who lived between three and six thousand years ago—a relatively short period by comparison with the quarter of a million years that Britain has been inhabited. During that long earlier period, following the arrival of the first hunters in these northern latitudes, there had been gradual but massive fluctuations in climate, and long glacial periods during which it would have been necessary to retreat southwards. Much of what is known about the general pattern of existence of early peoples derives from evidence as to their diet, for example from middens, and hunters are in this regard by their very lifestyle elusive. The few hunter-gatherers who were cave dwellers—and especially those from temperate regions in the same period—tell us that there were other dimensions to their lives than subsistence alone, for they have left us carved and modelled figurines in stone and clay, including those notorious ‘Venuses’ who look as though they were meant as wives for Michelin man. Even from a time as early as the Leptolithic period (say 35,000 to 10,000 BC) there have been found in France not only many specialized tools and weapons, but spectacular cave art. Among surviving artefacts are bones scratched in ways suggesting that some sort of counting was taking place, and on the basis of the grouping of incisions into sets of around thirty, claims have been made that some of the counting was of the days of the Moon.

Читать дальше