Elsewhere the landscape has been modified by humans less consciously, by providing congenial conditions for the river water crowfoot. The water crowfoots are a particularly lovely group of river plants. To the non-expert they all look pretty similar: crisp emerald weed buoyed up in the stream and then, in July, a snow in summer of glistening white flowers, which spill over the water in a way that seems to spell out the brief abundance of midsummer. The nine or so different forms and species to be found in England are all specialist. The pond water crowfoot has broad-lobed leaves which float on the still surface, in addition to dissected underwater foliage. At the other end of the scale are crowfoots of fast waters, whose only leaves are bunches of slender threads which run with the current – the ‘crow’s feet’. The river water crowfoot, Ranunculus fluitans , grows in gravel, and dies if it becomes too covered up by silt. Studies made on the river Lugg in Herefordshire show that the rubbly remains of fords or bridges which collapsed long ago have created a gravelly river bed which encourages crowfoot. The Lugg is in general a silty river, although it has natural riffles of gravel where the crowfoot also occurs. Elsewhere, however, known historical fords or bridge sites can be picked out every high summer when the crowfoot blooms – literally, living history. The same effects are visible in the river Wye in Hereford where the site of the early ford below the Bishop’s Palace is picked out in white in July when the water crowfoot is in flower. There is even a gap in the centre with no flowers where the material marking the ford was probably removed at a later date to allow passage for the boats, leaving a silty bottom to the river in that place unsuitable for the growth of water crowfoot. 9

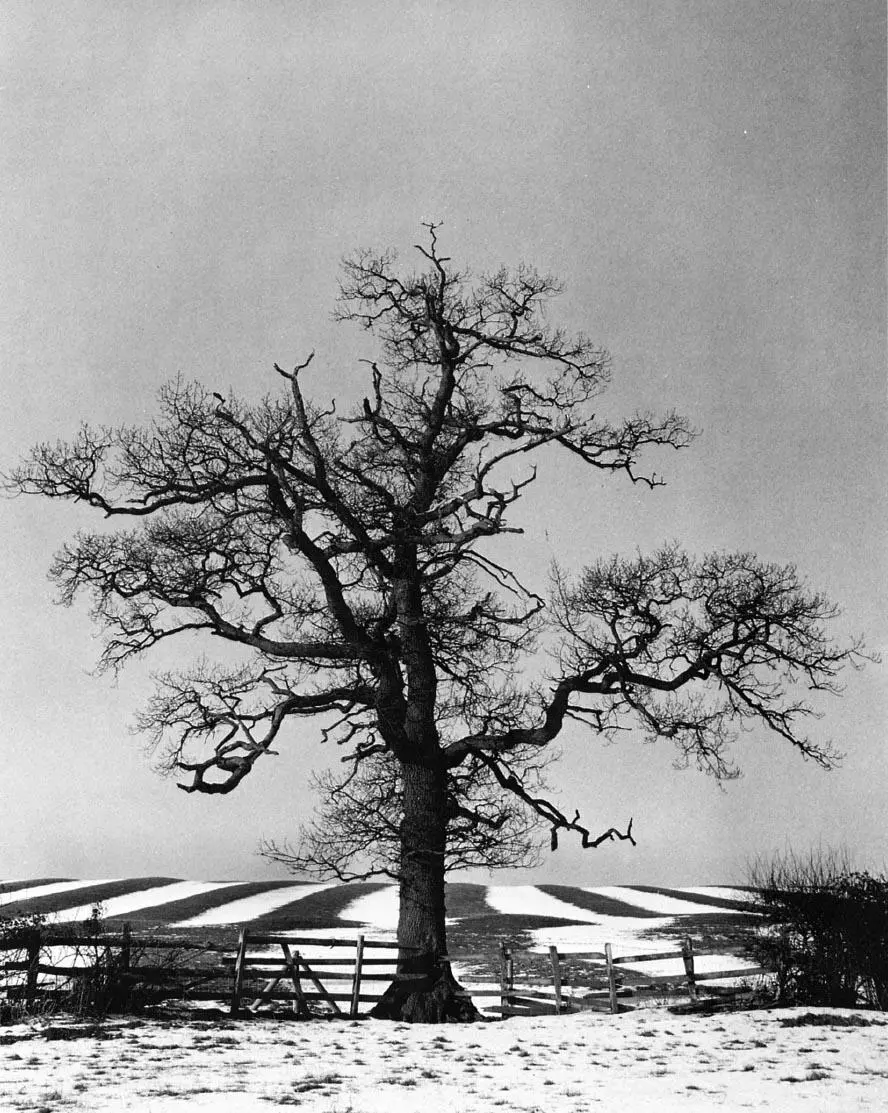

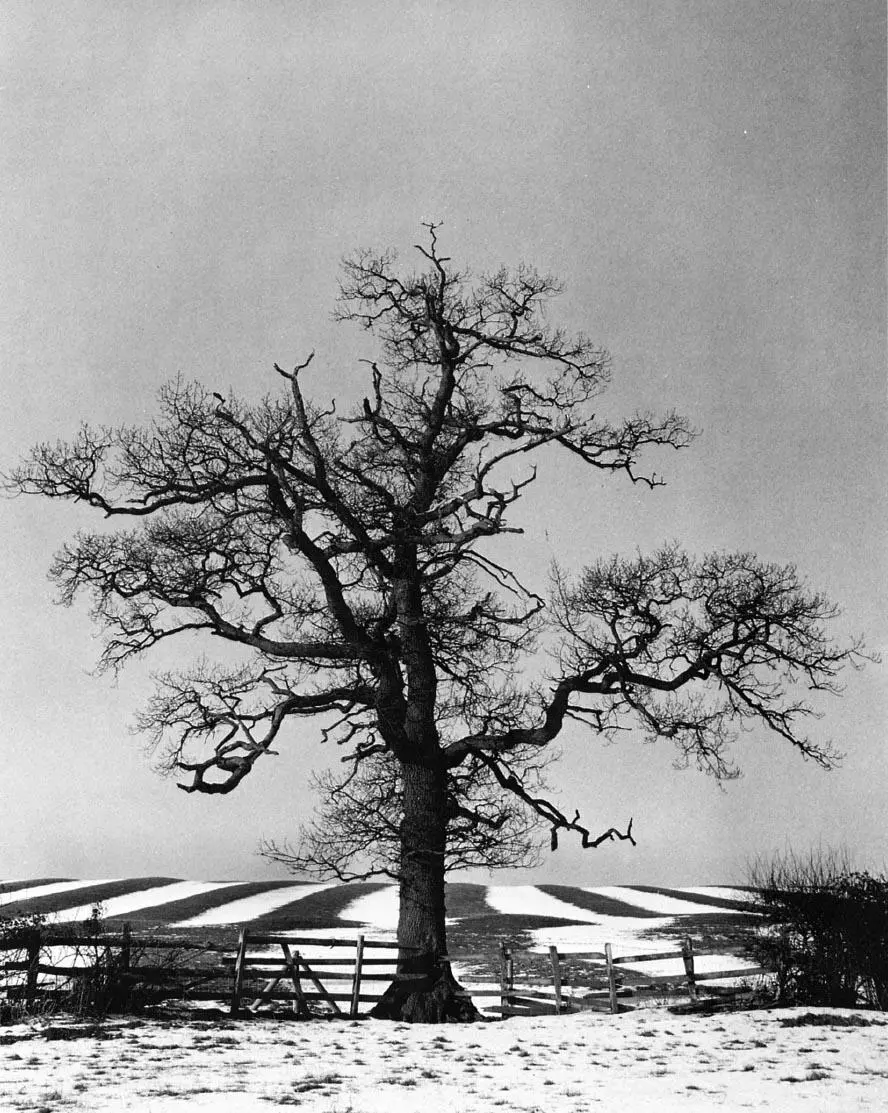

Our predecessors’ efforts to farm and drain the land can also be ‘read’, again in white and green, at a very different but particular moment of the year. If you stand on a hill in winter when there is a thaw, or look across an expanse from a motorway, especially in the Midlands, you can hardly miss the pattern of long parallel bands of snow, which are always the last to go from the hollows of the old ridge and furrow. In summer, too, you can read the ridge and furrow in an even more attractive way, although this is possible only on those few fields which have not been ‘improved’ to an all-over green of fertilized rye-grass. In such meadows there is a specialized flora for the damp furrow bottoms, subtly distinct from the flowers and grasses of the dry ridge crowns. The bulbous buttercup ( Ranunculus bulbosus ) prefers the tops, while the creeping buttercup ( R. repens ) favours the hollows. Ridge and furrow were formed any time between the early Middle Ages and the nineteenth century, as a result of ploughing up and down fields in parallel lines. This is generally thought to have been done deliberately, to improve drainage in the days before clay and, more recently, plastic field drains. In fields next to a river, the furrows are noticeably at right angles to the stream, although in some other places, where no obvious drainage benefit was gained, ridge and furrow seem to have been simply a by-product of the normal way of ploughing. If you look carefully, you may see some ridge and furrow which lie in a reverse-S pattern, a result of the logistics facing the medieval ploughman, who had to manœuvre eight oxen up and down a field. The Tudor ploughman had better-bred and better-fed beasts; so he required fewer of them to pull a plough, and was able to drive a straighter furrow. fn6

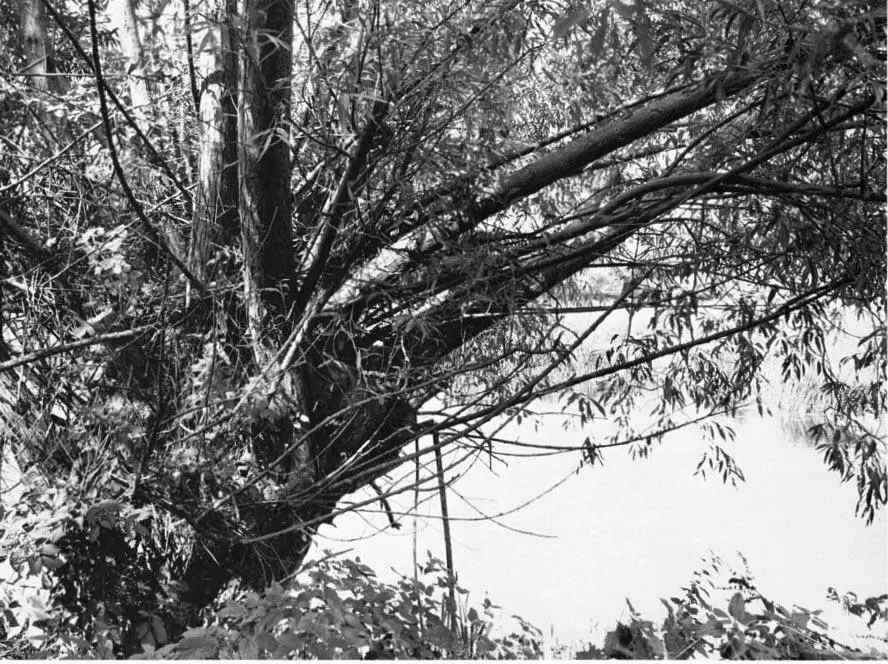

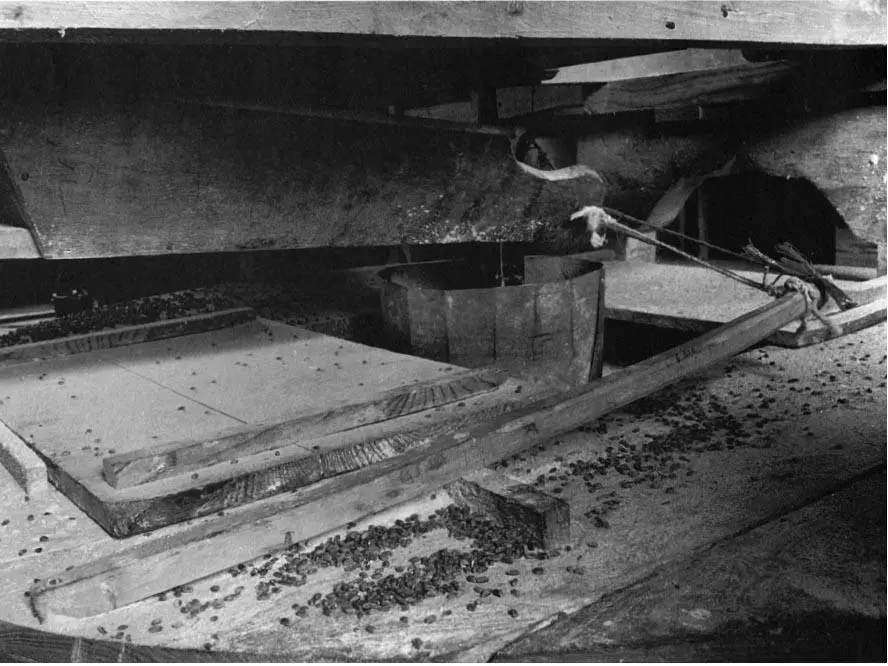

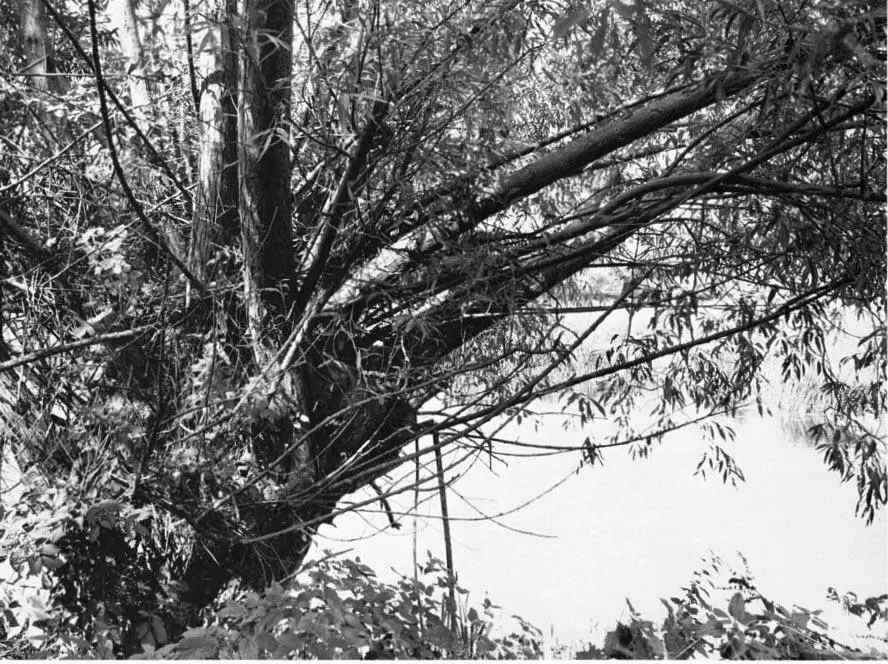

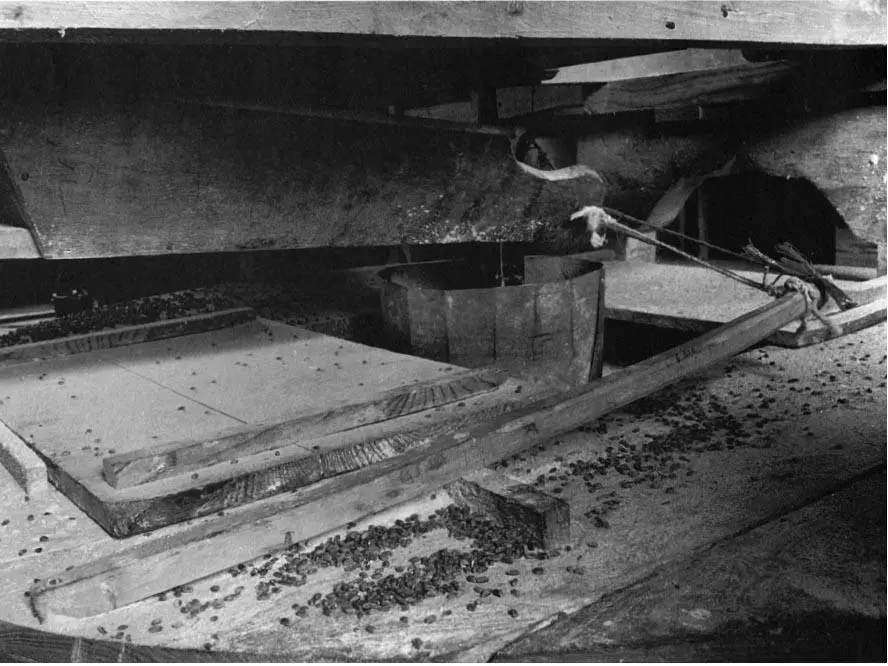

A pollard willow beside a water mill (top). ‘The miller’s willow’, a springy piece of timber, still gathered from the convenient pollard, for use as an essential part of the mill machinery. Charlecote, Warwickshire (bottom).

These are the monuments to generations of individual farmers ploughing and draining their fields. When, in the seventeenth century, the first real drainage engineers arrived, equipped with a literally world-changing technology, they too left their monument, in the shape of an entirely new landscape: the Fens. Despite their new-found power, however, they did not succeed in totally obliterating what had been before. Meandering across the geometrical landscape of straight ditches and square fields which the new engineers and their successors created, the winding courses of the original pre-drainage creeks and rivers can be seen especially clearly from the air. As they flowed on their – as it turned out – not so eternal journey from the hinterland of Ely and Cambridge to the Wash, these rivers deposited silt along their beds; and now, although the rivers vanished centuries ago, this silt stands out, a startling pale-fawn colour, as it snakes across the adjacent black peat of the Fens. Thus you can still pick out with ease the route of the ancient Wellestream, along which, in the fourteenth century, came cargoes of cloth from the Low Countries and silks from Italy, not to mention news of the dawning Renaissance, bound for Cambridge and beyond. Even more astonishing is that you can see the Wellestream more easily with every passing year. This is because the adjacent peat, as it is drained and dried out, wastes away by a process of oxidation on exposure to the atmosphere. Hence the old silt river beds, known in the Fens as ‘roddons’, are rising steadily as ridges above the ever-falling peat. They are landscape ghosts; but instead of fading away, they sharpen ever more clearly into focus.

Rivers have always been boundaries, as well as route-ways. They dictate the shape of many land-holdings, parishes, counties, and even parts of the Welsh and Scottish borders, as is well known to the poor river engineer who has to negotiate with different landowners, not to mention councils, on opposing banks as they try to promote their schemes. With boundaries go hedges, and some of those still remaining have been part of the farmed landscape since Saxon times, or possibly even earlier. Boundary hedges tend to be the oldest hedges, and a number of these are found bordering brooks and streams. Techniques developed by botanists and historians have shown that it is possible to assess the age of a hedge by the number of shrub species it contains. 10So the hedges that most interest the historian are those that most fascinate the botanist. To the layperson they are also arguably the most beautiful, with all the tangled richness and variety of oak, ash, buckthorn, elder, and wild rose. In general, a hedge will contain in a 30-yard length one shrub species for every century of its life. This is not an immutable law, but the correlation has been sufficiently demonstrated to be a valuable guide.

Snow picks out the ancient ridge and furrow, which is overlain by enclosure hedges. Warwickshire.

These are the relationships that print the character on the landscape. It is the same with the various damselflies in their clay and gravel streams, the water mill with its grey willows and grey wagtails, and the crowfoot crowning the ford and the curve in ridge and furrow. This is what the Englishness of England is made of, and it is this sense of place that we are currently in danger of losing, just as we come to understand it more clearly. It is far more important than any particular beetle or bird or ancient monument. The long evolution of the natural system, further evolved by human management, has given brooks and rivers individual characters as distinctive as their names, names which invest the Ordnance Survey map with an idiosyncratic quality ranging from poetry to comedy: the Windrush, the Swift, the Wagtail Brook, the Mad Brook, the Hell Brook, the Piddle, the Wriggle …

Читать дальше