THE CULTURAL HERITAGE OF RIVERS

It is not only wildlife that is at stake. Rivers represent a cultural heritage as well. Through aeons of geological time, rivers, in the wake of glaciers, have helped shape the very structure of our landscape. When civilization arrived, rivers shaped human history, and humans, in turn, began to shape the rivers.

From the time that the tribal Belgae and then the Romans invaded England, rivers dictated the positions of many towns and villages. It is believed that the great bluestones of which Stonehenge is constructed were floated up the Wiltshire Avon. Christianity came to England up a river, when St Augustine and his forty monks travelled to Canterbury up the Kentish Stour, ‘singing all the way’. Rivers were also highways of terror. The sleek hull of a Viking boat was specially designed to be shallow enough and narrow enough for use on navigable rivers, along which Norsemen brought fire and the sword. Along the waterways was carried most of the stone required to build our medieval cathedrals. When Whittlesey Mere was drained in the 1850s, a heap of dressed stone was found at the bottom of the lake, evidence of a medieval boating accident. It is thought that the cargo was destined for Crowland Abbey. fn5

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the harnessing of water power for mills, and river navigation, interlinked with a new system of canals, laid the foundation for the Industrial Revolution. Through all this change, rivers have continued to flow; but, for those who have eyes to see, the imprint of each generation remains, varying and concentrating the character of each stream that flows past our homes and our lives.

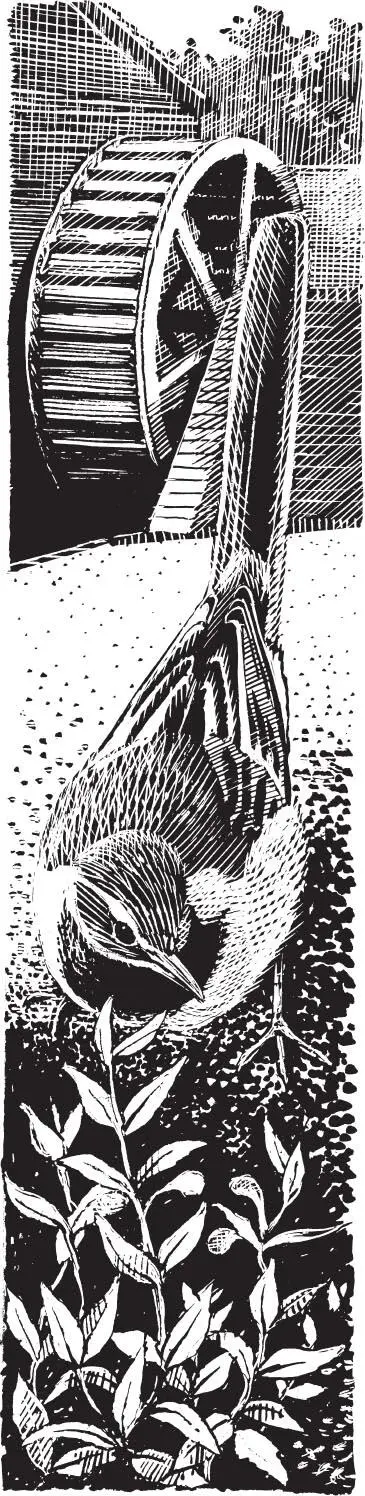

A good example of this is the water mill. The Romans introduced water mills to England, and the Domesday Book records as many as 5,624. All but a hundred of these mill sites can still be accounted for. Up and down rivers and brooks, the remains of some of these and many later water mills can be seen. In some cases, magnificent buildings, complete with all their machinery, still stand. Elsewhere there are just clues to former occupancy: foundations, a silted millrace, or the remnants of a weir, as described by Edward Thomas:

Only the idle foam

Of water falling

Changelessly calling,

Where once men had a work-place and a home. 6

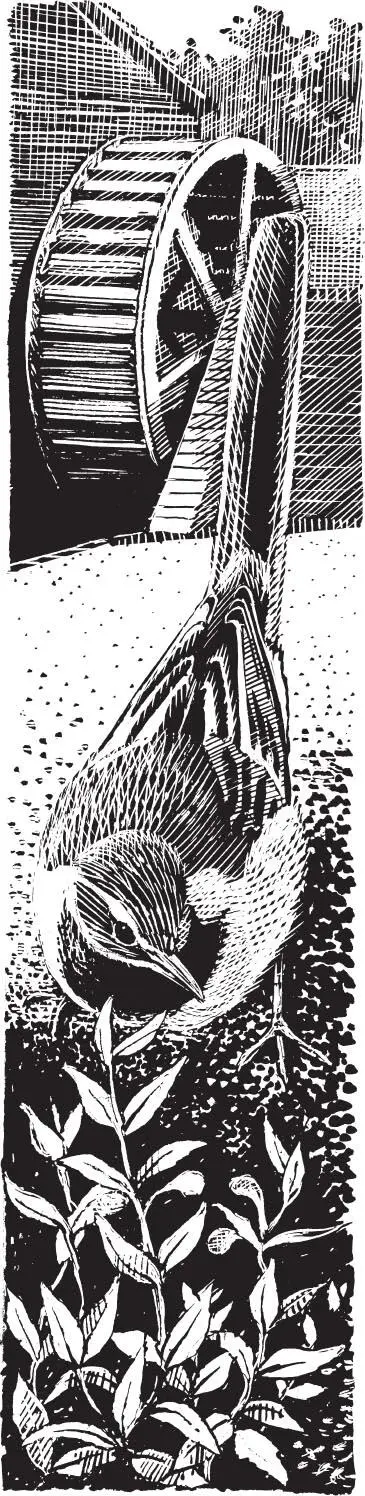

All this human interference with rivers, the building of millraces and millponds and, in some cases, quite major diversions of watercourses, did not destroy the essential character of rivers. On the contrary, it added to it, and not just in terms of the quality and character of the landscape, but also from the point of view of the wildlife. A tumbling weir creates the localized conditions of an upland brook wherever it crosses a silty lowland stream. Here grow the willow moss and liverworts found again in abundance only towards the sources of a brook. In the highly oxygenated water below a weir swim the little fish not known for nothing as the ‘miller’s thumb’: the flattened head of the fish was often compared with the thumb of the miller, worn it was said from testing the flour. Perhaps the loveliest of upland specialists associated with weirs and mill sites is the grey wagtail – grey in name, but not in appearance, with the flash of his canary-coloured chest. The grey wagtail nests in ledges and crevices of rock upstream, and finds a similar home in the crumbling walls and vertical structures of water mills. Edward Thomas may not have known that he was also making an ecological point when he pinned down so precisely the atmosphere and feel of these places:

Attractive colonizers of the mill weirs. Grey wagtail and the delicate leaves of skullcap.

The sun blazed while the thunder yet

Added a boom:

A wagtail flickered bright over

The mill-pond’s gloom. 7

Some of the wildlife of the water mill may owe its existence to a rather more conscious decision on the part of some long-dead miller. Growing along old millraces or near millponds are some of the stoutest and hoariest of pollard willows, which are the glory of any river bank. This is no accident. The willow was put to many uses by millers. An integral part of mill machinery was a simple spring known as the ‘miller’s willow’. In the most recent mills it was made of steel; but more commonly it was a piece of springy willow wood collected from a convenient pollard. Willow was also used for eel traps, and the fact of a river being carefully directed to drive a water wheel has always made water mills very convenient places to catch eels. The Luttrell Psalter of 1338 illustrates a water mill complete with eel traps which look very much as if they have been made out of pliant willow stems. Many medieval millers paid their rent to the lord of the manor in eels; and when the water mill in the centre of Stafford was pulled down after the Second World War, the laconic miller expressed as his only regret: ‘I shall miss the eels.’

More recently, eel traps have been built into the systems of weirs and sluices of water mills. Yet these structures, too, add variety and local character to rivers. The joints in a timber lock-gate or the eroding mortar of a sluice often provide congenial conditions for gipsywort or skullcap, with its clear blue flowers. Both these delicately proportioned plants have more difficulty competing with other vigorous vegetation on the open river bank than they do in the neat crevices provided for them by mill structures. The structures themselves were often built of local materials. Before the advent of railways, it was cheaper to do this than to import materials from far afield. Later, bricks were commonly imported, but even these, including the splendid ‘blues’ of the industrial Midlands, added their individual stamp to river landscapes. Nevertheless, it is surprising how often local builders simply took advantage of what was at hand. In 1985 a land-drainage scheme was carried out on the river Erewash near Eastwood in Nottinghamshire. This is the river which flows as a constant theme through the novels of D. H. Lawrence. Just opposite the point where the brook that runs past Lawrence’s old home joins the Erewash itself stands a mill sluice. In the normal course of events this would have been ‘tidied up’ – wiped out as part of the scheme and conveniently buried. But in this case the enlightened engineer was concerned to do precisely the opposite, and as the digger pulled back the rubble, an area of wall was exposed, which looked for a moment as if it were made entirely of shiny cream bones. This turned out to be pottery waste, a surviving memorial to a now vanished china factory in the local town. There it now stands, its cracks colonized by ferns and wormwood – nothing especially beautiful in itself, but a piece of history and natural history, with literary associations thrown in.

Builders in the wetlands did more than that, however. They built their homes out of the materials of the river bank itself. Whereas in most parts of England, thatched roofs were made of locally available straw, in the lowlands, especially in East Anglia, the common reed was used – the same plant that provides a home for a whole hierarchy of warblers, moths, and bees. And very good thatch it made. It is still often known as Norfolk reed; and in contrast to ordinary straw thatch, which has a lifetime of thirty years at most, a well-laid thatch of Norfolk reed may last as long as eighty years. In the wettest wetlands of all grows an even tougher thatching material, one of our most ancient natural crops: the giant saw sedge, Cladium mariscus . This, one of the dominant plants of the undrained Fens, can still be seen on the roofs of some of the houses between Ely and Newmarket. In some cases this most durable, but increasingly unobtainable, material is used as a capping ridge to a thatch of Norfolk reed. In other places, where even the Norfolk reed is scarce, the reed is used as a capping ridge to straw thatch. The final flourish in this humanizing of the natural landscape is given by an individual, as the thatcher in Ronald Blythe’s Akenfield explains: ‘We all have our own pattern; it is our signature you might say. A thatcher can look at a roof and tell you who thatched it by the pattern.’ 8

Читать дальше