Along with this burgeoning sense of pride went a deepening sense of responsibility to the country’s army and the country’s dead. ‘Would it have been possible, think you, to have concealed and slurred over our failures?’ demanded W. H. Russell, the great Times war correspondent who brought home the incompetence of the High Command in the Crimea to a British public demanding aristocratic heads; ‘No: the very dead on Cathcart’s Hill would be wronged as they lay mute in their bloody shrouds, and calumny and falsehood would insult that warrior race, which is not less than Roman, because it too has known a Trebisand and a Thrasymene.’

With the desolating Retreat from Kabul behind them, and the horrors of the Indian Mutiny only months ahead of them, Victorian England was getting used to extracting what comfort it could out of defeat. Here, however, is a note that would not have been heard even forty years earlier. Through the summer of 1815 there had certainly been collections and subscriptions the length of Britain for the widows and orphans of Waterloo, but the sense of responsibility and debt that Russell articulates, the recognition that the dead of the Crimea had their claim on the life of the nation was something very different in the relationship of Britain and her army.

It was one thing to talk like this, one thing for the Americans to hallow the soil of Gettysburg – it was American soil and American dead on both sides – but it was another to turn a distant piece of Russia or Turkey or any other bit of Europe into a little piece of England. At the end of the Crimean War in 1856 there had been 139 cemeteries of varying sizes scattered on the heights around Sevastopol and the Alma, but within twenty years this number had shrunk to eleven and then to one, as a hostile world of nomadic grave-robbers, winter frosts, earthquakes, vandals and grazing cattle took its random revenge on the men who had humiliated Mother Russia and reduced Sevastopol to ruins.

Perhaps the only surprise is not that there are so few surviving graves from Britain’s eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European wars, but that there are any at all. For those who cheerfully suffered the miseries of a Crimean winter, the work of the British Army in the Crimea was manifestly Christ’s work, but for all those countries that Britain fought against or even with, for Islamic Turkey or Orthodox Russia, for its Soviet successors who found themselves the custodians of Lord Raglan’s viscera, or Spanish nationalists recalling the sack of San Sebastián, the graves of Britain’s soldiers were not the sacred places of a burgeoning British mythology, but symbols of national humiliation, exploitation and desecration.

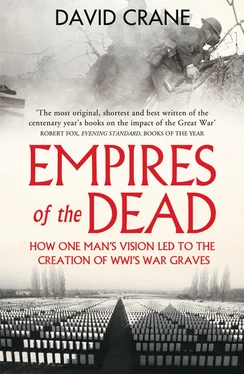

And then, out of nowhere, all that changed. In 1914 the number of surviving British war graves from Portugal to the Ionian Isles could be counted in their handfuls. Four years later they numbered in their hundreds of thousands. A war that had been fought on a hitherto unimaginable, industrial scale had been commemorated in kind. Something like a million British and Empire soldiers, sailors and airmen had been killed and on gravestones, memorials and monuments across the battlefields of the Western Front, Palestine, Mesopotamia, East Africa, Greece and Italy the task had begun of ensuring that their names would not be forgotten. ‘Imagine them moving in one long continuous column, four abreast,’ an early commentator at the Cenotaph Armistice Day service once said, giving graphic visual meaning to the sheer scale of the task that Britain had taken on,

as the head of that column reaches the Cenotaph the last four men would be at Durham. In Canada that column would stretch across the land from Quebec to Ottawa; in Australia from Melbourne to Canberra; in South Africa from Bloemfontein to Pretoria; in New Zealand from Christchurch to Wellington; in Newfoundland from coast to coast of the Island, and in India from Lahore to Delhi. It would take these million men eighty-four hours, or three and a half days, to march past the Cenotaph in London.

It is hard to know what is more extraordinary, the success of the attempt or the seismic shift of sensibility that brought it about in the first place. A ‘corner of a foreign field’ that for centuries had been no more than a scattered collection of neglected graves could now only be bound by walls fifty miles in length. How was it that nations and governments that had squandered lives in such obscene profusion could suddenly become so protective of their memory? How was it that a post-war Britain marked by class division and mutual suspicion could achieve its most democratic expression in the celebration of its dead? How did a country and empire that was historically so inimical to militarism and regulation, find its most potent expression of ‘Britishness’ in the straight lines, regularity, and enforced conformity of its war cemeteries? What, ultimately, lies behind these cemeteries and memorials? Grief? Pride? Gratitude? Guilt? Atonement? Reparation? Political acumen? Which was it? Catharsis, or ‘the old lie’ – ‘ Dulce et Decorum est ’ – that the poet Wilfred Owen, killed in the last week of the war, wrote of?

The fact that these questions are not more often asked is a tribute to the remarkable success with which the process of commemoration was carried out. Success carries with it a sense of its own inevitability and the images of Britain’s war cemeteries – the immaculate rows of graves, the memorials, the flowers and Crosses of Sacrifice, the biblical inscriptions – are so visually and imaginatively compelling that it is hard to realise that there was nothing preordained or self-evident about them. Nor, either, were they once the sacred cows that they now are. They did not appear without a struggle. They were as much the product of debate and argument as they were an expression of national unity, and they brought about divisions that were bitter and lasting. This is now largely, and perhaps properly, forgotten but it would have been surprising if it had been any other way. A traumatised society was dealing with death, grief, pride and anger on an unprecedented scale and it had little to guide it. A nation characterised by a deep and self-conscious class awareness was forced to cope with a war that was as indiscriminate in its killing as the plague. Where, in the twentieth century, was it to find the equivalent of that universality of understanding that raised Battle Abbey, or lies behind the Uccello memorial? How was it to balance the claims of the individual and of the nation? How does a Christian society remember its Muslim, Hindu or Jewish dead? How does it juggle the just claims of victory and the dictates of a wider, healing vision? How, even before you have begun to address these cultural questions, do you begin the vast task of commemorating the million casualties of a war that obliterated every vestige of human identity in the way that the great battles of the Western Front had done?

That answers were found and took the form they did is largely the work of one man. They came at the end of a century that had seen a gradual but profound change of attitude to its armies. They came too just a year after the centenary of the Battle of Leipzig and the fiftieth anniversary of Gettysburg had raised the Western world’s consciousness of its historical debts. And they emerged, of course, from long cultural traditions, from the country’s Christian roots, and from a human piety that is older even than those. If history can ever be said to belong to the individual, then it is the history of Britain’s war cemeteries and the process by which they came into being. Along with the trenches – their mirror image and polar antithesis – they are how most of us now see the First World War. And yet the identity of the man responsible for them is largely forgotten. Almost everyone, asked for the name of the commander responsible for the slaughter of the Western Front, would, fairly or not, come up with Haig. Most, asked for the architect of the Cenotaph, could make a stab at Lutyens. But the man who mediated between them, who made it possible for a country to come to terms with the slaughter and unbearable debt it owed its dead, is scarcely better known now than the unidentified thousands whose graves only bear the inscription ‘Known unto God’. His name was Fabian Ware.

Читать дальше