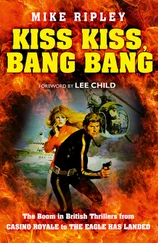

Within a genre as big as crime fiction, which could be described as a broad church (albeit an unholy one) readers tended to specialise often to a slightly frightening degree. There are those who only read spy stories (and some who only read spy stories set in Berlin), those who only read the Sherlock Holmes canon, those who refuse point blank to read anything written after 1945, those who only want to read about serial killers, those who always prefer the private eye novel, those who disparage the amateur sleuth preferring police detectives, and these days there are those naturally light-hearted optimistic readers of nothing but Scandinavian crime fiction.

Thankfully only a few crime fiction readers go as far as some science fiction fans and attend conventions dressed as their favourite fictional heroes but all like the security of identifiable categories and so some attempt must be made to define the terms used in this book.

As a recognisable genre, the thriller is certainly as old if not older than the detective story which, casually ignoring the interests of students of eighteenth-century literature and languages other than English, is generally dated from Edgar Allan Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue in 1841. With reluctance, the honours could also go to America, with James Fenimore Cooper’s The Spy (1821) and The Last of the Mohicans (1826) for the earliest examples of the spy thriller and the adventure thriller .

Already the dissection of the term ‘thriller’ has begun, yet by the time the British had flexed their writing muscles things were becoming clearer. Both Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883) and Sir Henry Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines (1885), published in the same decade in which Sherlock Holmes took his first bow, were fully-formed adventure thrillers. They were adventure stories which thrilled and distinctly different from the detective story, which could of course be thrilling but in a different, perhaps more cerebral, way. If that was not confusing enough, the 1890s saw the early days of the spy novel – albeit in the shape of a string of xenophobic potboilers which revelled in the fear of an invasion of England by Russia, France, or even Germany. 2They were certainly meant to be thrilling, if not hysterical, but a quality mark was soon achieved with Erskine Childers’ The Riddle of the Sands (1903) and the work of John Buchan, seen by many as the Godfather of the quintessential British thriller, although he preferred the term ‘shocker’ presumably in the sense that his stories were electrifying rather than revolting.

When the Golden Age of the English detective story dawned, it suddenly seemed important that the thriller was publicly differentiated from the novel of detection which offered readers ‘fair play’ clues to the solution of the mystery, usually a murder. At least it seemed important to the writers of detective stories, who saw themselves as, if not quite an elite, then certainly a literary step up on the purveyors of potboilers and shockers.

The Golden Age can be dated, very crudely, as the period between the two world wars, beginning with the early novels of Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers (when it actually ended is still a matter of some debate – an often interminable and sometimes heated debate). Although a boom time for detective stories, it was also a boom time for spy thrillers. Donald McCormick in his Who’s Who in Spy Fiction (1977) claims that the years between 1914 and 1939 were the most prolific period of the spy thriller, the public’s appetite having been whetted by the First World War and real or imagined German spy-scares. ‘The spy story became a habit rather than a cult’ was his polite way of saying that this was definitely not a Golden Age for the thriller. Names such as Edgar Wallace, E. Phillips Oppenheim, Sydney Horler and Francis Beeding (Beeding’s books were publicised under the banner ‘Breathless Beeding’ or ‘Sit up with …’ after a review in The Times had declared that Beeding was an author whose books made ‘readers sit up [all night] until the book is finished’) are now mostly found in reference books rather than on the spines of books on shelves, whereas certain luminaries of the Golden Age of detective fiction, such as Christie, Sayers, Margery Allingham, Anthony Berkeley and John Dickson Carr are still known and respected and, more importantly, in print somewhere. 3

Back in the day though, the fact of the matter was that the Oppenheims and Breathless Beedings et al were the bigger sellers. Edgar Wallace’s publishers once claimed him to be the author of a quarter of all the books read in Britain (which even by publishing standards of hype is pretty extreme) and they were to inspire in various ways, often unintended, a new generation of thriller writers. In 1936, a debut novel, The Dark Frontier , arrived without much fanfare marking the start of the writing career of Eric Ambler, who was later to admit that he had great fun writing a parody of an E. Phillips Oppenheim hero. 4Two decades later, the eagle-eyed reader of a certain age could spot certain Oppenheim traits in another new arrival, James Bond. In fact, the reader didn’t have to be that eagle-eyed.

The question of what was a thriller, and how seriously it should be taken, seemed to exercise the minds of the writers of detective stories and members of the elite Detection Club, confident in the superiority of their craft, rather than the thriller writers themselves.

One writer closely associated with the Golden Age, though happy to experiment beyond the confines of the detective story, was Margery Allingham. In 1931, Allingham wrote an article for The Bookfinder Illustrated succinctly entitled ‘Thriller!’ trying to explain the different categories then evident in crime fiction. It was a remarkably good and fair analysis of the then current crime scene, identifying five types (and one sub-type) which made up the family tree of the ‘thriller’, which were:

Murder Puzzle Stories – which could be sub-divided into (a) ‘Novels with murder plots’ by writers ‘who take murder in their stride’ (such as Anthony Berkeley), and (b) ‘Pure puzzles’ such as those by Freeman Wills Crofts;

Stout Fellows – the brave British adventurer or secret agent, usually square-jawed and later to be known as the ‘Clubland hero’ type (as written by John Buchan);

Pirates and Gunmen – the adventurers and gangsters as found in the books of American Francis Coe and the prolific Edgar Wallace;

Serious Murder – novels such as Malice Aforethought by Francis Iles (Anthony Berkeley) which Allingham put ‘in the same class as Crime and Punishment ’;

High Adventures in Civilised Settings – crime stories ‘without impossibilities and improbabilities’ for which she cited Dorothy L. Sayers as an example.

Whether Dorothy L. Sayers was pleased with this somewhat lofty and isolated categorisation is not recorded, but it is likely that she bridled at being lumped, even in a specialised category, in the general genre of thrillers. She was crime fiction reviewer for the Sunday Times in the years 1933–5 and was not slow off the mark to say that a novel she did not approve of had ‘been reduced to the thriller class’. Responding to a claim, real or imagined, that she had been ‘harsh and high hat’ about thrillers, she claimed to hail them ‘with cries of joy when they displayed the least touch of originality’, whenever she found one that is, which seemed to be rarely and she clearly felt the detective story the purer form. (This in turn provoked the very successful thriller writer Sydney Horler, creator of ‘stout fellow’ hero Tiger Standish, to remark rather acidly that Miss Sayers ‘spent several hours a day watching the detective story as though expecting something terrific to happen’.) 5

Читать дальше