I should insert here a warning: fans of Eric Ambler (1909–98) and Graham Greene (1904–91) will feel themselves short-changed. Both these authors were immensely influential on the form and tone of the thriller genre (novels and films); indeed, their surnames became adjectives frequently used by reviewers. It was high praise indeed for a thriller to be called ‘Ambler-esque’ and everyone knew exactly where ‘Greene-land’ was. Yet neither of these giants were a product of the period under scrutiny as they had cemented their reputations two decades previously, although both were still producing work of high quality, notably Ambler’s Passage of Arms (1959), The Light of Day (1962) – famously filmed as Topkapi , and The Levanter (1972); and Greene’s The Quiet American (1955), Our Man in Havana (1958), and The Comedians 1966). Their legacy and importance in the genre will be acknowledged, though not in enough detail to satisfy their dedicated fans. I have also relegated Leslie Charteris and Dennis Wheatley to the pre-war era for, although ‘The Saint’ was an immensely popular figure on British television in the early Sixties, Charteris had ceased to produce full-length novels and Dennis Wheatley’s novels in the period under scrutiny tended towards the historical or the occult stories with which he had made his name in the Thirties.

One limitation is not self-imposed, and that is the absence of women writers. Adventure thrillers and spy stories tended to be what is known in the book trade as ‘boys’ books’ or, pejoratively, ‘dads’ books’ and were to a very great degree, written by men – some might say men who had never grown out of being boys. A notable exception was Helen MacInnes, a Scot based in America, whose first novel had appeared in 1939. By the Sixties, she was a well-established and popular writer and had three notable bestsellers in that decade, but she, like Ambler and Greene, was not a product of that period when Britain ruled the thriller-writing waves and so gets an honourable, but passing, mention here. And it should not be forgotten that it was in the Sixties that some rather talented female writers, notably P. D. James and Ruth Rendell, were laying the groundwork for a revival in the British detective story and crime novel.

It is difficult to pin-point the exact end of this ‘Golden Age’ (or purple patch) of dominance by British thriller writers. One option would perhaps be the death of Alistair MacLean – the biggest name in the adventure thriller market – in 1987, or alternatively the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989, which threatened to put many a spy-fiction writer out of business. In truth, the writing was on the wall (if not the Berlin one) from roughly the mid-Seventies onwards as the Americans, slightly late as usual, entered the fray.

The beginning of the boom is rather easier to identify. The 1950s were grey and austere for a supposedly victorious wartime nation whose empire was starting to crumble. You might say Britain had been expecting you, Mr Bond …

Chapter 1:

A QUESTION OF EMPHASIS

You can smell fear. You can smell it and you can see it and I could do both as I hauled my way into the control centre of the Dolphin that morning. Not one man as much as flickered an eye in my direction … they had eyes for one thing only – the plummeting needle on the depth gauge.

Seven hundred feet. Seven hundred and fifty. Eight hundred. I’d never heard of a submarine that had reached that depth and lived.

Alistair MacLean, Ice Station Zebra

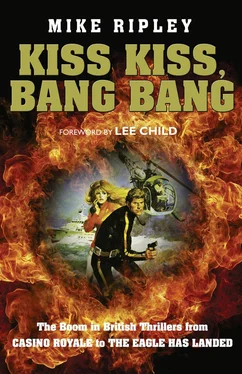

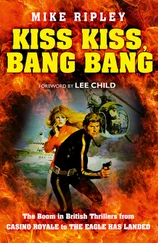

Was it a Golden Age or an explosion of ‘kiss-kiss, bang-bang’ pulp fiction which reflected the social revolution – and some would say declining morals – of the period? Both are reasonable explanations, depending on your standpoint, for the extraordinary growth in both the writing and reading of British thrillers, between 1953 and 1975.

Popular fiction, as opposed to literary or ‘highbrow’ fiction was always, well – popular; but suddenly the thriller seemed to be out-gunning all other forms. Writing in the middle of the Swinging Sixties, in his economic history Industry and Empire , the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm noted that since 1945, ‘that powerful cultural export, the British detective story, has lost its hold, conquered by the American-patterned thriller.’ Professor Hobsbawm was certainly correct in that the traditional British detective story had been replaced by the thriller as a cultural, and in fact economically valuable, export but wrong in suggesting they were ‘American-patterned’. This was a very British boom.

The British, or probably more accurately the English detective story had flourished in the period, roughly, between the two World Wars, a period which earned the epithet ‘Golden Age’ and was characterized, often unfairly, as the era of ‘the country house murder mystery’ or the ‘whodunit?’ It had given rise to the concept of ‘fair play’ whereby the reader was presented with clues to solving the puzzle presented, ideally before the fictional detective did, and the puzzle element was very important. There were even ‘rules’ (fairly tongue-in-cheek ones) on what was and was not allowed in a detective story, and a self-selecting, totally unofficial, Detection Club of the leading practitioners of the art to set the standards of good writing – or just standards in general.

After WWII tastes changed and readers began to demand something other than an intellectual puzzle. Cynics may say that the launch of the board game Cluedo in 1949 was an ironic final nail in the coffin of the ‘whodunit?’ – all those fictional cardboard characters being reduced to actual pieces of cardboard. Of course, it wasn’t the end; it was a period of cyclical dip and transition. Readers were looking for exotic settings, not country houses; heroes and heroines who often acted outside the law rather than plodding policemen; suspense rather than a puzzle; more realistic violence rather than a ridiculously over-elaborate murder method; and, above all, action and excitement at a time when, in the Sixties, everything seemed exciting and moved much faster.

For a period of more than two decades the British thriller delivered on all counts, and on a truly international level. It may not have been a Golden Age but it was certainly a boom time.

This is not a work of literary criticism or comparative literature; it is a reader’s history of one specific category, or genre, of popular fiction – the thriller – over a particular period when British writers dominated the bestseller lists at home and abroad. There will be little, if any, discussion of heroic mythology, social individualism, the atemporality of the appeal of the thriller, the symbiotic relationship between hero and conspiracy, or genre theory. Those debates are left to others on the grounds that, to paraphrase E. B. White: dissecting a thriller is like dissecting a frog – few people are really interested and the frog dies. 1

But there has to be some attempt to define the term ‘thriller’, a term used as loosely in the past as ‘noir’ is today (‘Tartan Noir’, ‘Scandi Noir’, etc.) to describe an important segment of that exotic fruit which is generally known as crime fiction. Whether it matters a jot to the reader who simply wants to be entertained is debatable, but again, it probably does. Crime fiction is a recognised genre, just as horror, science fiction, romance, fantasy, westerns and supernatural are all genres of popular fiction and genres tend to have dedicated followers.

The idea of genre fiction evolved in the late nineteenth century and blossomed in the Thirties with the advent of cheaper, paperback books with crime fiction among the first instantly identifiable genres thanks to the famous green covers used by Penguins and logos such as the Collins Crime Club’s ‘gunman’. Dedicated readers were steered to genres they liked and genre readers appreciated the guidance – though they did not want to read the same book again, they did want more of the same.

Читать дальше