Most digestive problems, whether serious or commonplace, don’t present just one symptom. Usually we notice a couple, perhaps more. Here’s an example: George notices that he’s constipated, and occasionally sees flecks of bright red blood on the toilet paper; Sally feels a lot of discomfort when she goes to the toilet, especially when she is straining, and is also irritated by anal itching. George and Sally each have piles. They have the same condition, but they have differing symptoms. George’s main problems are constipation and bleeding, Sally’s are discomfort and itching. This is another reason why it is sometimes difficult to tell what is causing a particular health problem.

Analysing your symptoms in an almost detached way is part of the answer. For this reason, Section 1 focuses on the common symptoms like diarrhoea, constipation, bleeding, and wind and bloating. Very few of us wake up and think, ‘I think I’ve got inflammatory bowel disease.’ More likely we’ll say, ‘This diarrhoea is getting me down, I wonder what’s causing it and how I can stop it.’ This section explains what can cause these symptoms and offers a variety of practical ways we can help relieve them.

Section 1 also discusses how we can get the best from our doctors – by knowing what to ask, how to ask and what to expect from medical consultations, and describes the major tests that are used by doctors to explore and identify gut problems.

CHAPTER 1

A Quick Anatomy Lesson

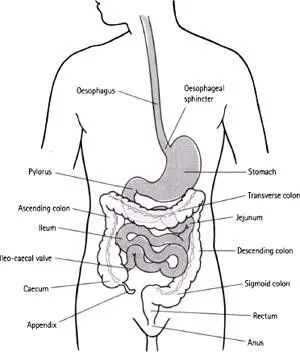

First, let’s go back to the classroom. It is easier to understand why things go wrong – and how we are affected – if we know a little about the anatomy of the gut.

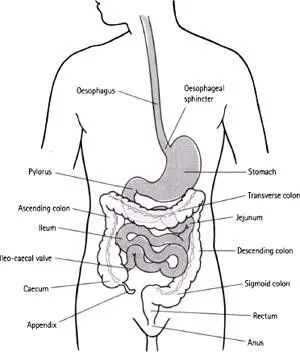

The digestive system starts at our mouth and ends up at the other end – the anus. When people talk about ‘guts’ they can mean pretty much anything, from the throat to the stomach to the intestines, although generally, most people think of the stomach and the small and large intestines when they say ‘gut’. Vagueness may be okay when we’re chatting with friends, but there’s little room for it in the doctor’s office. Being specific helps our doctors understand what we’re talking about. We might think we’re being fairly exact when we say ‘abdominal’, but a doctor could easily wonder whether we mean the stomach, the small intestines or the large bowel (colon and rectum). And should he ask which it is, it helps to know what he’s talking about.

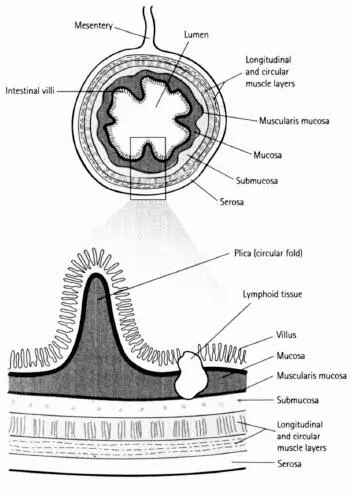

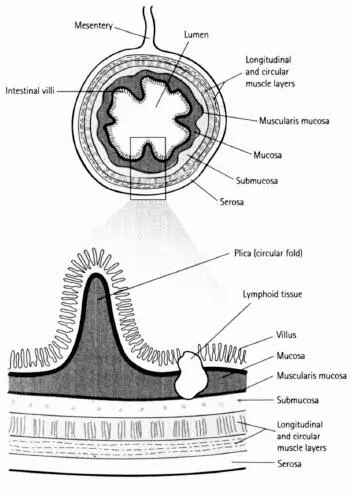

A few minutes spent looking at the drawing overleaf should help. This shows the whole digestive system, its various parts and their medical names. The other diagrams provide a little more detail about the lining of the intestines. There are different layers, each of which performs different functions. The whole of the digestive system is hugely vascular (that is, rich in blood vessels). A staggering quantity of blood passes through it – some 40 per cent of our blood supply is diverted through the digestive system after a meal, so that the blood can absorb the goodness our food delivers to our bodies. That’s why it isn’t a good idea to embark on strenuous exercise soon after eating – it puts too many demands on our body systems.

The Mouth to the Oesophagus

The mouth is the first organ of digestion. Teeth chew our food, physically breaking it down, and the inside of our mouth contains glands that produce saliva – not only when we eat food but also when we’re just thinking about it. Saliva is important. This liquid, which is neutral to slightly acidic, not only starts the chemical process of digestion, but it lubricates each mouthful, helping us to swallow properly. We produce about 1.7 litres (about 60fl oz) of saliva every day. One of the main enzymes contained in saliva is called amylase, which starts breaking starch down into more basic sugars. When we swallow, food enters the first ‘tube’ – the oesophagus, which is about 25cm (10in) long. The oesophagus doesn’t do anything to digest food. Waves of muscle contraction (called peristalsis) help push the food down the oesophagus. These muscular contractions are so strong that you can drink a glass of water while standing on your head.

Food enters the stomach through a ring of muscle (sphincter) that prevents the stomach contents from travelling back up the oesophagus – the one normal exception to this is during vomiting. The stomach is so stretchy that it can hold up to 2 litres (about 70fl oz) of fluid. While food is in the stomach it is subjected to both physical and chemical action. Stomach acids – mostly hydrochloric acid (one of the strongest acids known to man) – reduce the stomach contents to a porridge-like consistency, while the stomach also mechanically ‘churns’ the food during the four hours or so that food stays there. Because the stomach contents are very acidic, we get ‘burning’ sensations when we vomit, have indigestion or gastric reflux, as the contents bubble back up into the oesophagus. After a while, the sphincter muscle (called the pylorus) that holds the lower end of the stomach closed starts to relax, allowing the partly-digested food to trickle out into the first portion of the small intestine.

As food is squirted through the pylorus, it enters the first part of the small intestine, the duodenum. Here, more digestive chemicals are introduced, further breaking down the food. Bile, for example, an alkaline substance that is made in the liver, is pumped out by the gall bladder when needed. Bile acts as a detergent and emulsifying agent, breaking fats down into small droplets. Pancreatic enzymes break down carbohydrates and proteins: amylase acts on carbohydrates and trypsin and chymotrypsin help digest proteins. Fats are also further broken down by lipase, another pancreatic enzyme.

The next section of the small intestine, the 3 metre (10ft) long jejunum, is where most of the nutrients released from food start to be absorbed. The walls of the jejunum are completely covered with tiny finger-like projections called villi. Millions of these millimetre-high folds line the intestinal walls, their purpose being to massively increase the surface area to make absorption of nutrients into the bloodstream effective (see figure overleaf). If the small intestines didn’t have villi, they would need to be about 2 miles long to do the same job – in fact, they are only about 6 metres (20ft) long. After the jejunum comes another 3 metre (10ft) long section of small bowel commonly known as the ileum. Although there are still many villi here, there are fewer than in the jejunum. The ileum continues to absorb nutrients into the bloodstream, but the focus here is more on water and salts; as food progresses through the small bowel, the consistency of it becomes thicker and more ‘sludgy’. In the very last part of the ileum, vitamin B12 is absorbed.

The Large Intestine – the Colon, Rectum and Anus

Once food has travelled through the small intestine, most of the essential nourishment has already been absorbed. What enters the colon is watery slurry. It passes through the ileo-caecal valve into a stretchy section of the colon called the caecum. The appendix hangs down from the caecum and is a relic, doctors believe, from when the human diet was far higher in plant matter than it is today. The appendix may have contained special bacterial agents that digest cellulose – much like grass-eating animals have. In the colon, water is reabsorbed from the watery slurry, making the waste more solid. What have now become faeces (‘poo’) slowly travel along the last portion of the colon until they reach the rectum, where they are expelled through the anus.

Читать дальше