‘I am not I’: yet Charles Ryder manifestly is Evelyn Waugh. Brideshead Revisited contains as large a dose of autobiography as Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield or Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu . So who, then, was the ‘thou’ who was and was not ‘he or she’? The ‘they’ who were and were not ‘they’? What was ‘the household of the faith’ that was and was not Brideshead? What were the events that inspired the novel?

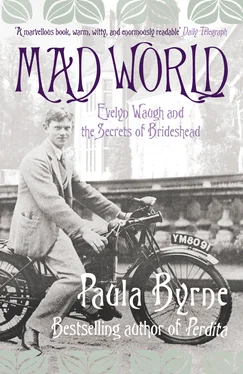

This biography sets out to find the hidden key to Waugh’s great novel, to unlock for the first time the full extent to which Brideshead encodes and subtly transforms the author’s own experiences. In so doing, it illuminates the obsessions that shaped his life: the search for an ideal family and the quest for a secure faith. The solution to the mystery can be found in that magical year of 1931. The hidden key will also unlock several of Waugh’s other major novels, including his very best one, A Handful of Dust . And it will bring us to a secret that dared not speak its name.

But we must begin with two very different childhoods. And then we must go, as Captain Charles Ryder does when he begins his recollections, to Oxford, in the years immediately after the Great War.

CHAPTER 1 A Tale of Two Childhoods

‘My name is Evelyn Waugh I go to Heath Mount school I am in the Vth Form, Our Form Master is Mr Stebbing.’

So begins his first extant literary composition, a brief self-portrait called ‘My History’, written in September 1911, at the age of seven. It is the work of a boy of strong opinions and sharp wit:

We all hate Mr Cooper, our arith master. It is the 7th day of the Winter Term which is my 4th. Today is Sunday so I am not at school. We allways have sausages for breakfast on Sundays I have been watching Lucy fry them they do look funny befor their kooked. Daddy is a Publisher he goes to Chapman and Hall office it looks a offely dull plase. I am just going to Church. Alec, my big brother has just gorn to Sherborne. The wind is blowing dreadfuly I am afraid that when I go up to Church I shall be blown away. I was not blown away after all.

The child, William Wordsworth once said, is father to the man. Here is Evelyn Waugh the writer in embryo: a good hater of bad masters, a spectator of the world who can make ordinary things (like sausages) look funny. He is just going to church: eventually he will be blown in the direction of Rome. His household is comfortably middle class: prep school, domestic servants (Lucy in the kitchen with sausages), the home dominated by Daddy, with his important-sounding job (Publisher) in his dull London office. And a big brother who has just gone to a big, renowned public school: Sherborne. Some years later, an ill wind will blow dreadfully from there, redirecting Evelyn to another school.

Mother is not mentioned in this first little sketch. But Evelyn was closer to her than he was to his father, chiefly because Arthur Waugh, managing director of the publisher Chapman and Hall, idolised his first-born son Alec to an absurd degree. Albeit with good intentions: Arthur was determined not to be like his own father, a sadistic bully who rejoiced in the nickname ‘The Brute’. Arthur, educated at Sherborne School and then New College, Oxford, had married Catherine Raban, a gentle girl from an English colonial family originally hailing from Staffordshire, in 1893. Their first child, Alexander (‘Alec’) was born in 1898. Arthur called him ‘the son of my soul’ and, as the boy grew, developed a relationship with him that was intense, exclusive and all consuming.

Evelyn was born on 28 October 1903 at the family home in Hampstead. When Evelyn was four and the family moved to a larger house, closer to Golders Green, Alec left for boarding school. This might have been the moment when the younger son could have come out from under the wing of Mother and Nurse. But he didn’t. Evelyn’s relationship with his father always remained difficult. There is already a hint of irreverence in that early sketch, with its dismissal of Chapman and Hall’s offices as ‘a offely dull plase’. Evelyn would grow into a rebellious teenager who carefully cultivated a satirical, worldly, disengaged persona, not least in order to set himself against what he perceived to be his father’s nauseating sentimentality and histrionic tendencies.

Arthur Waugh, who was very well respected and connected in the London literary world, had the tastes of his age and class: Shakespeare, the King James Bible, Dickens and cricket (this was the era of the legendary Dr W. G. Grace). The Dickens copyright was the jewel in Chapman and Hall’s crown. Arthur Waugh was rotund, diminutive, with twinkling eyes and candyfloss white hair. Ellen Terry, the greatest actress of the age, had the perfect name for him: ‘that dear little Mr Pickwick’.

In such a literary household, it was probably inevitable that Evelyn should grow up literary – or at the very least that he should view his own family through the filter of books and plays. Arthur Waugh seemed to spend all his time acting out roles. When he greeted visitors, he was the over-hearty Mr Hardcastle of Oliver Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer . In deploring the ingratitude of his sons, he was Shakespeare’s King Lear. Above all, he was Mr Pooter in George and Weedon Grossmith’s Diary of a Nobody . ‘Why, I am Lupin!’ Evelyn cried out delightedly when he first read the book, identifying instantly with Pooter’s rebellious, loutish and troublesome son. It remained a favourite book, which he regarded as the funniest in the English language. The hilarious clashes in values and attitude between the respectable lower-middle-class civil servant Pooter and his reckless, extravagant son mirrored to a tee Evelyn’s sense of his own disjointedness from his father. It is no coincidence that in Brideshead Revisited Lady Marchmain reads Diary of a Nobody aloud to lighten the tension generated by her son Sebastian’s drunken behaviour at dinner.

Evelyn later displayed his father’s gift for adopting theatrical roles, particularly in his middle age when the part that he cast for himself was, as he put it in his autobiographical novel The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold , ‘that of the eccentric don and testy colonel’: ‘he acted it strenuously, before his children … and his cronies in London, until it came to dominate his whole outward personality’.

Arthur Waugh would have been delighted by Ellen Terry’s Pickwick comparison. He often read Dickens aloud in his marvellously theatrical voice. Though Evelyn, ever the Lupin, affected to despise his father’s theatricality (‘his sighs would have carried to the back of the gallery at Drury Lane’), he also later acknowledged Arthur’s verbal gifts: ‘he read aloud with a precision of tone, authority and variety that I have heard excelled only by John Gielgud’. Had Evelyn lived to witness the celebrated 1981 Granada Television adaptation of Brideshead , he would have found it fitting that Gielgud stole the show with his performance in the role of Charles Ryder’s father. Arthur kept Evelyn and his friends enthralled with his readings of Dickens and Shakespeare and his favourite poets. In the autobiography A Little Learning Evelyn wrote of how his father’s love of English prose and verse ‘saturated my young mind, so that I never thought of English Literature as a school subject … but as a source of natural joy’.

The account of Waugh’s happy childhood in A Little Learning belies the common view that he was deeply ashamed of his middle-class, suburban upbringing. He paints a delightful picture of the pleasures of life at Underhill, the family home on the edge of Hampstead Heath. He felt lucky to be at a day school and not to be sent away to board: ‘it was a world of privacy and love very unlike the bleak dormitories to which most boys of my age and kind were condemned’.

Читать дальше