The penetration of countless tiny balls of shot through his skin left Meredith moaning in pain. “Get a car and get me in it,” he implored the others at the scene. An ambulance arrived quickly, and within minutes Meredith was being raced back along his hiking route, bound for a Memphis hospital. Emergency room physicians concluded that his wounds were not life-threatening, although they could have been if the shooter had been closer or his aim more accurate.

James Meredith collapsed in the road after he was ambushed and shot in rural Mississippi on June 6, 1966. Credit 2

Doctors shaved the back of Meredith’s head and dug as many as 70 pellets out of his scalp, back, limbs, even from behind an ear, before they questioned their effort. Although only a fraction of the 450 or so shotgun pellets fired toward Meredith had found their mark, countless balls of shot remained embedded in his flesh. Yet it was so time-consuming—and so painful—to remove them, that doctors decided to leave the rest alone. He wouldn’t be the first person to walk around with bird shot under his skin. Soon after, a local news reporter found a medical resident familiar with the case and asked him about the patient’s condition. The doctor-in-training replied with a candor that, although shocking today, would have seemed unremarkable at that time in the South. “If he had been an ordinary nigger on an ordinary Saturday night,” the man observed, “we’d have swabbed his ass with merthiolate [an antiseptic] and sent him home”

But Meredith was not an ordinary man, black or otherwise, and his shooting would have a seismic influence on the turn of events beyond his own world.

“I wanted to give hope to a barefoot boy. I was a barefoot boy in Mississippi myself for 16 years.”

James Meredith, explaining one of the reasons behind his planned walk through Mississippi

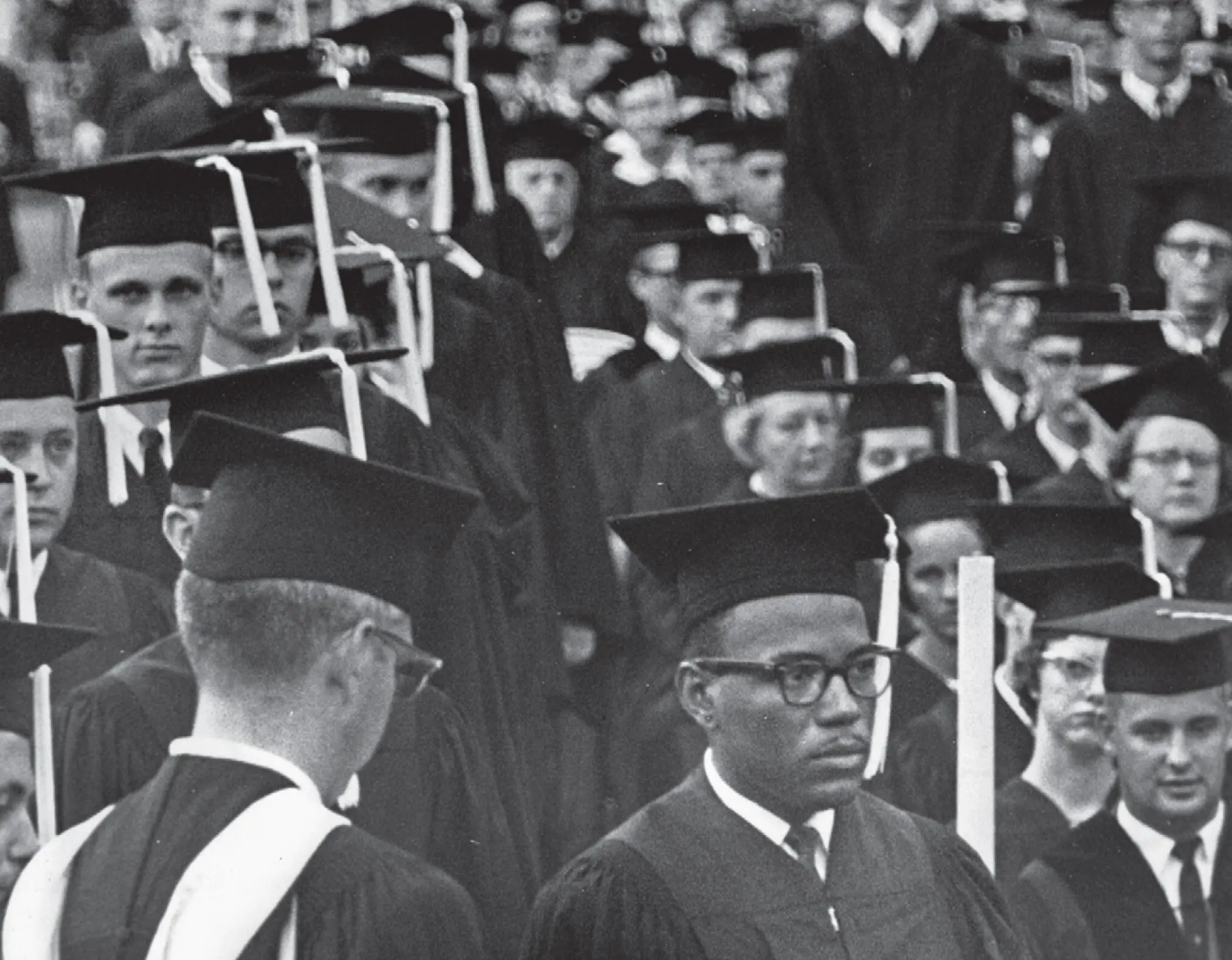

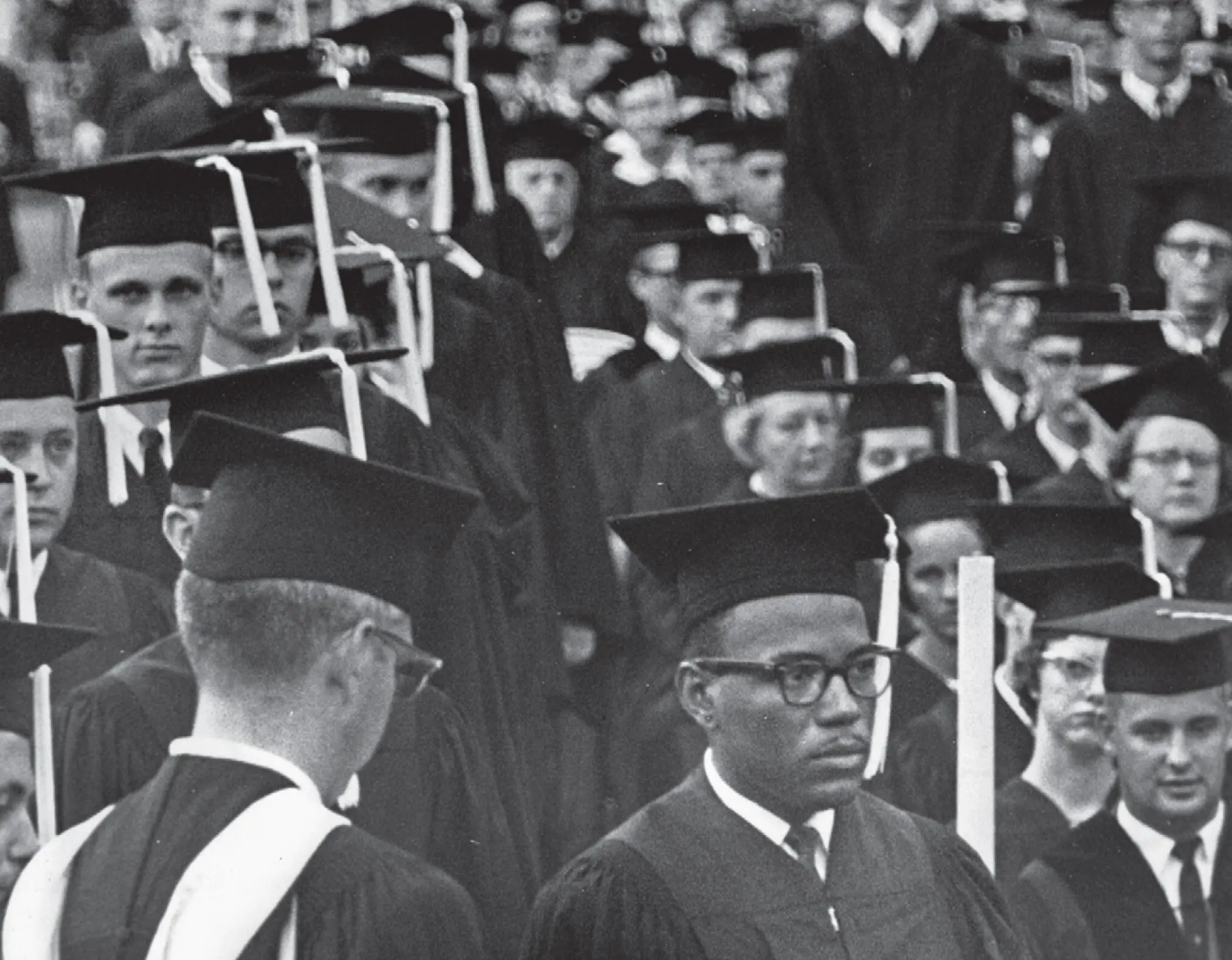

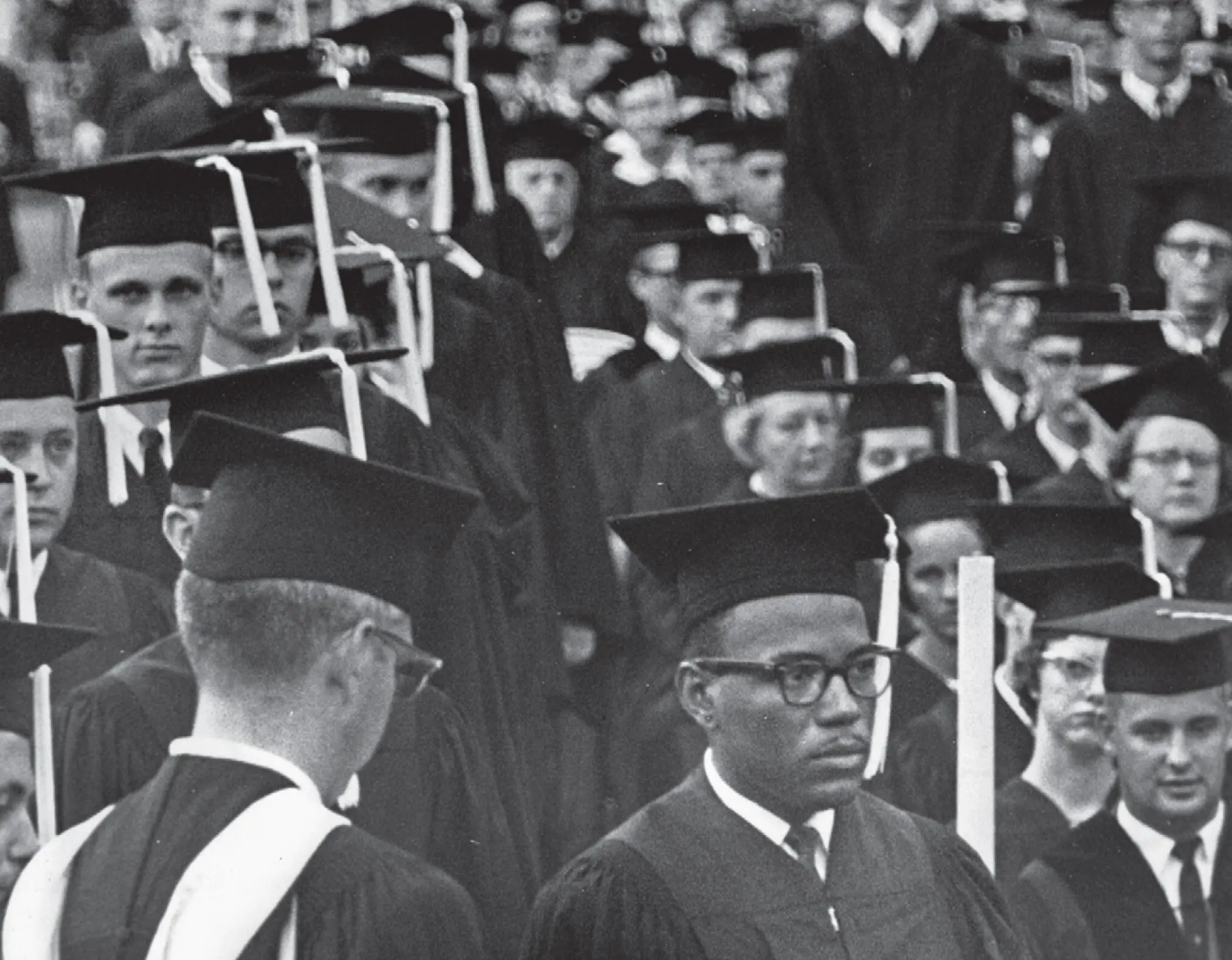

James Howard Meredith graduated from Ole Miss in Oxford amid a sea of white faces on August 18, 1963. He was the first African American to earn a degree from the institution, having integrated it the previous year. Credit 3

JAMES MEREDITH was already famous before he got shot on June 6, 1966. Indeed, his fame probably made him a target for attack, and his fame certainly accounted for why his shooting made the national news. Otherwise he would have been just the latest overlooked victim of white-on-black violence in a state where whites had used violence—and fear of violence—to secure their supremacy since the era of slavery.

At the time of his birth in 1933, Meredith’s parents chose to name him simply J. H., using initials in place of a first and middle name. His family lived on a farm outside Kosciusko, Mississippi, and his parents’ decision represented both an act of courage and an acknowledgment of the challenges their son would face growing up in the segregated world of the Deep South.

Even names held power then.

Social custom during that era dictated that blacks address whites by adding titles of respect to their names, such as Mr., Mrs., and Miss. This gesture emphasized the place of whites at the top of a race-based social order. Whites reinforced the subservient stature of African Americans by routinely addressing them by first name only. Whites also often converted the given names of blacks into childish nicknames that might last a lifetime. Meredith’s parents chose not to give him a proper name, such as James, which could have become a source of humiliation if whites called him Jimmy instead.

DATES WALKED: June 5–6 MILES WALKED: 28 ROUTE: Memphis, Tennessee, to south of Hernando, Mississippi

Despite his exposure to this world of white supremacy, Meredith emerged from his childhood with a remarkable sense of his potential and self-worth. Maybe it was the pride he felt because his great-grandfather had been the last leader of the region’s Choctaw Nation. Maybe it was the power of those childhood initials. Maybe it was the security and independence that land ownership brought to his parents as they raised their 11 children. Whatever the causes, the result was that J. H. Meredith had a fierce determination to make something of himself.

And he had complete confidence that he could do it.

When he turned 18, J. H. added names to his initials and became James Howard Meredith; he needed a full name in order to join the Air Force. A few years before, President Harry S. Truman had ordered the integration of the armed forces of the United States, so Meredith was among the first wave of recruits to serve in an integrated Air Force. He spent most of the 1950s in the military, culminating in a three-year posting to Japan. In 1960 he returned to Mississippi, newly married, and in pursuit of further education for both himself and his wife. Initially the couple enrolled at all-black Jackson State University, but, in 1961, Meredith set his sights on transferring to one of the most revered all-white institutions of the South: the University of Mississippi, otherwise known as Ole Miss.

Federal marshals and other U.S. security personnel stood guard to ensure that onlookers remained orderly when Meredith registered for classes at the University of Mississippi on Monday, October 1, 1962. Credit 4

Ever since his teens, Meredith had dreamed of going to his home state’s flagship university. Having served in an integrated military, and having heard newly elected President John F. Kennedy’s call in 1961 to national service, Meredith dared to imagine integrating Ole Miss. Others had tried and failed; perhaps he could succeed. So he applied. And he persisted in claiming his right to be admitted regardless of his race. His audacity triggered a fury among staunch segregationists and led to widespread opposition to his enrollment. Months of legal battles ensued, going all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which, on September 10, 1962, upheld Meredith’s right to attend the school.

Yet when Meredith appeared on campus to enroll in classes, the state’s governor personally blocked him from doing so. The lieutenant governor performed the same maneuver on a subsequent enrollment attempt. This struggle went on for days, and, at its climax on the last day of September, local segregationists besieged the federal forces that had taken up guard outside the university’s administrative offices. After dark, the mob grew increasingly hostile and began attacking the armed personnel. Two observers died during the ensuing violence in a conflict that some likened to the final battle of the Civil War. News coverage of the unfolding drama ensured that Meredith gained national fame along with his eventual admission to the university. Everyone knew who he was and what he had achieved.

Even the use of tear gas failed to disperse a mob of angry whites who rioted at Ole Miss in an effort to prevent the university’s integration. Cars set ablaze by the segregationists still smoldered when Meredith enrolled the next morning, October 1, 1962. Credit 5

Meredith had exhibited unusual courage and determination during his Ole Miss enrollment struggle. He seemed unflappable. Able to endure any insult without being provoked to retaliate. Always restrained under pressure. Focused on some future spot on a horizon that sometimes only he seemed able to see. Meredith maintained that focus for the rest of his studies even though he required constant protection by U.S. marshals and other military personnel. After combining his credits from Jackson State with three semesters of coursework at Ole Miss, he earned his college degree on August 18, 1963.

Читать дальше