The symbolic fall of the Berlin Wall seemed like a new beginning. Although the stories that had been hiding behind it were more prosaic than we had been led to believe by the propaganda of the Cold War, at a personal level they were both shocking and awe-inspiring. Individual stories of endless, grinding poverty, cruelty and darkness emerged into the light. Each story that was brought to me seemed more gruelling and shocking than the one before.

Out of that darkness, however, it was possible to make out glimmers of hope as good people made huge sacrifices and put their own lives on hold in order to help. A variety of ghostwritten books followed. There were tales of hopelessly crippled and apparently mad orphans being saved by Western surgeons and by the love of patient foster families. Bombed orphanages were rebuilt by soldiers, charities were set up and families who had been separated for a generation were reunited. There was so much to do but no shortage of people who wanted to help, and who then wanted to tell the stories of the horrors and the miracles they had witnessed.

For a writer it was a Pandora’s box: scenes of unspeakable evil and personal struggles, often leading to happy endings. I wrote the story of a small boy who had been tied up and imprisoned in an orphanage cot for the first four years of his life, condemned by the authorities as sub-human because he was believed to be both physically and mentally handicapped, who was saved by a volunteer and given a full life in the West. I did one for a soldier who rebuilt a bombed orphanage for a local town in his own time and went on to create a full-scale charity, and another for an English woman who had been trapped in Eastern Europe as a teenager just before the Second World War, not escaping back to her family in the West until the Iron Curtain finally fell just over half a century later. I also helped tell tales for some of the pioneering business pirates and ex-politicians who built vast fortunes as communism crumbled and a new frontier-land of opportunities opened up for those bold and ruthless enough to grab them.

These stories were the absolute stuff of life, horrifying and inspiring, sickening and uplifting, frightening and dramatic. I seldom cried while I was actually there in the orphanages, or actually listening to the stories (as Graham Greene once said ‘There is a splinter of ice in the heart of a writer’), but I confess that when I came to write the stories the ice would inevitably melt into tears. The goal then was to ensure that the readers would be equally moved to tears at the same time as being unable to stop turning the pages.

That ‘splinter of ice in the heart of a writer’ Greene talked about helps a great deal when listening to stories that have the potential to break your heart. Ghosts, like other authors, need to be able to remain objective, slightly distant, hovering above the emotion, watching and noting what it looks and sounds like. But at the same time we need to understand what it feels like in order to convey it to the reader.

If the person who is telling you the story is crying, then you need to be able to make the reader cry too when you reproduce the story on the page, but you won’t be able to do that if you get too close. You need to be interested in the story, amazed by it, moved by it, but you cannot let it cloud the clarity of your own thoughts while you are interviewing.

Sometimes I have sat with people who are in floods of tears when they tell their stories. More often they struggle to hold in those tears, their chins trembling, their eyes and noses running involuntarily, their voices cracking as they battle bravely on with the memories that cause them so much pain and which they want so much to exorcise. It is a cliché that many of the soldiers who had the most traumatic times in the trenches of the First World War never wanted to speak about their experiences once they got home. The same rule has applied to others who have suffered since in different ways but times have changed. The medical profession came to understand about post-traumatic stress and people are now encouraged to talk about their traumas in order to learn how to cope with them. It is still never an easy thing for most damaged people to do.

My role is to sit and wait, quiet and encouraging; never criticising them, never comforting them, never rushing them, just passing the tissues, assuring them there is no problem and waiting for them to feel able to continue.

Readers want to be moved to tears by stories, just as they want to be moved to laughter or to shrieks of fear. They want to ‘feel something’. A ghostwriter must catch the elements that produce that effect and reproduce them later on the page, not during the interview.

I guess therapists and analysts must work in the same way because often when I get to the end of the interviewing process the subject will say they feel like they have just been through a course of therapy. They are nearly always grateful to have been able to unburden themselves but still the fact remains that there was a splinter of ice required in order to achieve it – and that troubles me a little.

It isn’t only once work is under way that a ghost has to remain detached. Often the people who make initial enquiries about hiring a ghostwriter have heartbreaking tales to tell. To have to warn them that the fact that they have lost a child in appalling circumstances or been tortured for months by an oppressive regime does not necessarily mean that they will get a publishing deal, can seem unbearably cruel – but to give them false hope would be far crueller.

I suppose it’s the same in many other professions. A paediatrician must spend a large proportion of his or her time having to give heartbreaking news to parents. A press photographer sent to a war or disaster zone, a policeman dealing with the victims of a terrible crime or having to break the news of a death to a family. All these people can only function effectively in their jobs if they become detached in some way, deliberately inserting Greene’s cold, hard, necessary splinter of ice.

Since these are my confessions, I guess I must reveal that I was more than a little in love with Twiggy when I was a schoolboy in the sixties. Although she was about four years older than me she did not seem as intimidatingly mature and grown up as the other models and film stars that my generation of boys were busily lusting after. In fact, she didn’t look that different to some of us when we were made-up to appear on stage in school plays. It was quite possible to imagine yourself on a date with her, despite her extraordinary and unusual beauty – not to mention her enormous global fame and iconic status.

So, when a publisher rang in the mid-nineties and asked if I would come to the office for lunch with Twiggy as she was looking for a ghostwriter, it set all my nostalgia glands tingling.

The lunch was delightful. Twiggy was delightful, and even though I didn’t get the job (again I was told they had decided a woman would be more suitable), I felt I had an anecdote that might at least interest, and possibly even impress, my children.

‘I had lunch with Twiggy last week,’ I announced casually over Sunday lunch.

‘Twiggy?’ my eldest daughter exclaimed, looking just as stunned as I thought appropriate for such a momentous event. ‘That’s amazing. We’re doing her at school, in history.’

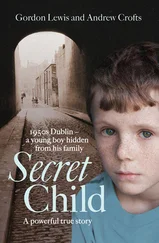

Abused children find a voice

At the beginning of the nineties I started to receive phone calls and letters from people who wanted to write about abuses they had suffered in their childhoods. These were not people who had had the misfortune to be born in countries that were enduring brutal dictatorships, civil wars or ethnic cleansing campaigns, these were people who had been born and brought up in democratic, peacetime Britain, a country that prided itself on being civilised, with developed social welfare services.

Читать дальше