When Jacques Cartier visited Funk Island on his first voyage to Newfoundland in May 1534 his crews filled two boats with the birds in less than half an hour, and every ship salted down five or six barrelfuls. Two years later the voyager Robert Hore came to one of the Penguin Islands or Funk Island, and found it full of auks and their eggs. They spread their sails from ship to shore and drove a great number of the birds on board upon the sails; and they took many eggs. By 1578 it was the normal thing for French and British crews in the Gulf of St. Lawrence or on the Newfoundland Banks to stock their ships with auk-meat, stopping at the Bird Rocks, or Penguin Islands or Funk Island, and driving the great auks aboard on planks. Today there is nothing but old ships’ logs and travellers’ diaries to record where the western auks once lived in thousands, save on Funk Island, where a great many bones have been found.

It seems clear, from the account of Peters and Burleigh, that the great auk became extinct in Newfoundland in about 1800. George Cartwright (1792), who lived in Newfoundland Labrador for most of the period 1770–1786, and who often sailed across the Straits of Belle Isle to northern Newfoundland, only logged personal meetings with great auks in his diary twice, on 4 August 1771 and 10 June 1774. On a visit to Fogo Island harbour on 5 July 1785 he wrote:

“A boat came in from Funk Island laden with birds, chiefly penguins. Funk Island is a small flat island-rock, about twenty leagues east of the island of Fogo, in the latitude of 50° north. Innumerable flocks of sea-fowl breed upon it every summer, which are of great service to the poor inhabitants of Fogo; who make voyages there to load with birds and eggs. When the water is smooth, they make their shallop fast to the shore, lay their gang-boards from the gunwale of the boat to the rocks, and then drive as many penguins on board as she will hold; for, the wings of those birds being remarkably short, they cannot fly. But it has been customary of late years, for several crews of men to live all the summer on that island, for the sole purpose of killing birds for the sake of their feathers, the destruction which they have made is incredible. If a stop is not soon put to that practice, the whole breed will be diminished to almost nothing, particularly the penguins: for this is now the only island they have left to breed upon; all others lying so near to the shores of Newfoundland, they are continually robbed. The birds which the people bring from thence, they salt and eat, in lieu of salted pork. It is a very extraordinary thing (yet a certain fact) that the Red, or Wild Indians, of Newfoundland should every year visit that island; for, it is not to be seen from the Fogo hills, they have no knowledge of the compass, nor ever had any intercourse with any other nation, to be informed of its situation. How they came by their information, will most likely remain a secret among themselves.”

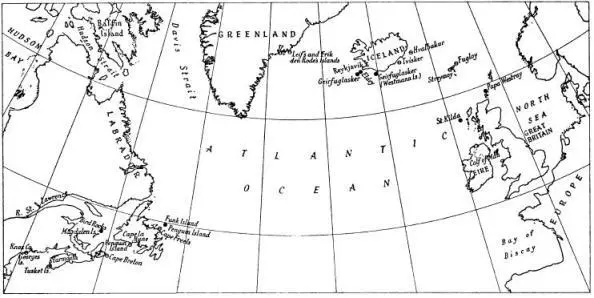

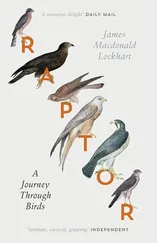

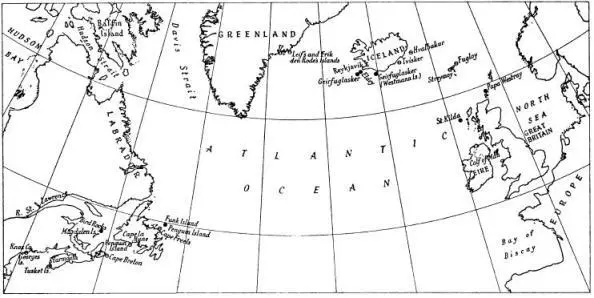

FIG. 13

Known (•) and putative (Θ) breeding-places of the great auk.

Nobody knows when the Norse-Gaels of St. Kilda came first to Hirta, their main island, and established Britain’s most interesting colony of wildfowlers. Certainly by 1549 there was a stable human community on St. Kilda, whose life was based to a large extent on “wyld foullis” (D. Monro, 1774). In about 1682 the Lord Register, Sir George M’Kenzie of Tarbat, gave an account (1818) of St. Kilda to Sir Robert Sibbald. He probably did not visit St. Kilda himself, but he says: “There be many sorts of … fowls; some of them of strange shapes, among which there is one they call the Gare fowl, which is bigger than any goose, and hath eggs as big almost as those of the Ostrich. Among the other commodities they export out of the island, this is none of the meanest. They take the fat of these fowls that frequent the island, and stuff the stomach of this fowl with it, which they preserve by hanging it near the chimney, where it is dryed with the smoke, and they sell it to their neighbours on the continent, as a remedy they use for aches and pains.”

When Martin Martin (1698), tutor to the son of the islands’ laird, the MacLeod of MacLeod, arrived at St. Kilda in June 1697 he wrote a classic and accurate account of its natural history, which included this:

“The Sea-Fowl are, first, Gairfowl , being the stateliest, as well as the largest Sort, and above the Size of a Solan Goose, of a black Colour, red about the Eyes, a large white Spot under each, a long broad Bill; it stands stately, its whole Body erected, its Wings short, flies not at all; lays its Egg upon the bare Rock, which, if taken away, she lays no more for that year; she is whole footed, and has the hatching Spot upon her Breast, i.e. a bare spot from which the Feathers have fallen off with the Heat in hatching; its Egg is twice as big as that of a Solan Goose, and is variously spotted, Black, Green, and Dark; it comes without Regard to any wind, appears the first of May , and goes away about the middle of June.”

We quote this in full, as it is really a most remarkable and convincing description. As we explain elsewhere ( see here) the interval between the first of May and the middle of June is about seven weeks, the combined incubation and fledging period of the great auk’s closest surviving relative, the razorbill. The description also otherwise fits the bird perfectly. Martin arrived at St. Kilda on 1 June 1697 by the calendar of his day, which would be 12 June by our present calendar. If great auks had actually been breeding on one of the islands (Soay would have been the most likely) in that year it is almost certain that he would have been shown them by the inhabitants, and made some comment thereon in his careful notes: as it is his passage that we have quoted reads very much as if the information in it had been taken from natives who themselves had seen the bird nesting and remembered it clearly, but not from Martin’s own observations. From this we conclude that the great auk nested at St. Kilda not in 1697, but within the memory of some alive in that year, i.e. most probably in the second half of the seventeenth century; we can also conclude from the account that its eggs were sometimes taken. The M’Kenzie information for c. i 682 also suggests breeding in this period.

The great auk appears to have been seen at St. Kilda occasionally after Martin’s visit. The notes of A. Buchan, who was minister on St. Kilda from 1705 to 1730, respecting the bird derive from Martin; but Kenneth MacAulay (1764) who was on the island for a year in 1758–59, alludes to irregular July visits (not every year) by the great auk; he did not see one himself. “It keeps at a distance from [the St. Kildans],” he writes, “they know not where, for a course of years. From what land or ocean it makes its uncertain voyages to their isle, is perhaps a mystery in nature.” After MacAulay’s visit the only certain records of great auks at St. Kilda are two: one was taken at Hirta in the early summer of 1821 and kept alive until August. In this month it was being taken to Glasgow by ship; near the entrance to the Firth of Clyde it was put overboard, with a line tied to its leg for its daily swim, and escaped. Another was found on Stac an Armin, the highest rock-stack in the British Isles (though no doubt the auk got ashore at the shelving corner), in about 1840, and was beaten to death by the St. Kildans L. M’Kinnon and D. MacQueen as they thought it was a witch. Obviously it had been a generation or more since any St. Kildan had seen a garefowl.

Читать дальше