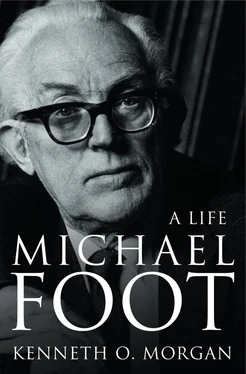

Kenneth O. Morgan

MICHAEL FOOT

A LIFE

DEDICATION CONTENTS COVER TITLE PAGE DEDICATION PREFACE 1 Nonconformist Patrician (1913–1934) 2 Cripps to Beaverbrook (1934–1940) 3 Pursuing Guilty Men (1940–1945) 4 Loyal Oppositionist (1945–1951) 5 Bevanite and Tribunite (1951–1960) 6 Classic and Romantic 7 Towards the Mainstream (1960–1968) 8 Union Man (1968–1974) 9 Social Contract (1974–1976) 10 House and Party Leader (1976–1980) 11 Two Kinds of Socialism (1980–1983) 12 Into the Nineties ENVOI: Toujours l’Audace SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY INDEX ABOUT THE AUTHOR PRAISE NOTES BY THE SAME AUTHOR COPYRIGHT ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

For Joseph

COVER

TITLE PAGE Kenneth O. Morgan MICHAEL FOOT A LIFE

DEDICATION DEDICATION CONTENTS COVER TITLE PAGE DEDICATION PREFACE 1 Nonconformist Patrician (1913–1934) 2 Cripps to Beaverbrook (1934–1940) 3 Pursuing Guilty Men (1940–1945) 4 Loyal Oppositionist (1945–1951) 5 Bevanite and Tribunite (1951–1960) 6 Classic and Romantic 7 Towards the Mainstream (1960–1968) 8 Union Man (1968–1974) 9 Social Contract (1974–1976) 10 House and Party Leader (1976–1980) 11 Two Kinds of Socialism (1980–1983) 12 Into the Nineties ENVOI: Toujours l’Audace SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY INDEX ABOUT THE AUTHOR PRAISE NOTES BY THE SAME AUTHOR COPYRIGHT ABOUT THE PUBLISHER For Joseph

PREFACE

1 Nonconformist Patrician (1913–1934)

2 Cripps to Beaverbrook (1934–1940)

3 Pursuing Guilty Men (1940–1945)

4 Loyal Oppositionist (1945–1951)

5 Bevanite and Tribunite (1951–1960)

6 Classic and Romantic

7 Towards the Mainstream (1960–1968)

8 Union Man (1968–1974)

9 Social Contract (1974–1976)

10 House and Party Leader (1976–1980)

11 Two Kinds of Socialism (1980–1983)

12 Into the Nineties

ENVOI: Toujours l’Audace

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

PRAISE

NOTES

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

Michael Foot has had a very long and colourful life. He was chronicler and participant in central aspects of British twentieth-century history. His first general election found him crusading for Lloyd George’s Liberal Party in 1929. His twentieth and last saw him campaigning for Labour in his old seat, Ebbw Vale/Blaenau Gwent, seventy-six years later. He spans the worlds of Stafford Cripps and Tony Blair. He was a doughty opponent of appeasement in the later 1930s: his book Guilty Men made him famous at the age of twenty-seven. He was vocal in condemning the invasion of Iraq in 2003. He stands, and feels himself to stand, in the great and honourable tradition of dissenting ‘troublemakers’, the heir to Fox and Paine, Hazlitt and Cobbett. He played in his life many parts. As icon of the socialist left, he was custodian and communicator of British socialism. He was the greatest pamphleteer perhaps since John Wilkes, a formidable editor, and author of a glittering biography of his idol, Nye Bevan. He was a scintillating parliamentarian, an inveterate critic and peacemonger as Bevanite, Tribunite and founder member of CND, yet also a belligerent patriot and internationalist from Dunkirk to Dubrovnik. He was a central figure and champion of the unions in the Labour governments of the 1970s, a key player in Old Labour’s last phase. Less happily, he was for almost three tormented years Labour’s leader. Perhaps most important of all, he was a deeply cultured and literate man whose learning was absolutely central to his politics. He was heir to the Edwardian men of letters, the Liberals Morley or Birrell, and politically more innovative than either. Over sixty years he was an inspirational and civilizing force, if a deeply controversial one. His passing will symbolize a world we have lost.

When Michael Foot asked me if I would write a new authorized biography, I was, of course, both excited and honoured. At the same time, I had some doubts. After writing a large biography of one veteran Labour leader, Jim Callaghan, I wondered whether it would be wise to write another, especially on someone so removed from Callaghan’s own wing of the party. Although Callaghan and Foot worked with immense loyalty as colleagues in the Labour government of 1976–79, they were very different as men and as democratic socialists. Someone who worked for them both told me that they were not ‘best buddies’, while Jim Callaghan himself, just before he died in March 2005, showed himself to be a bit wary of my new project. Another point was that, while I had never really been on the right in Labour terms since I first joined the party in 1955, I was not really Old Labour either, despite the stereotypes of amiable journalists who have vainly tried to depict me as its ‘laureate’. On the contrary, I have always been a liberal devolutionist rather than a state centralist (being Welsh may have something to do with that), while on several major issues my views were not those of Michael Foot, notably on CND and on Europe. Although an admirer of Bevan (whose features adorn the sticker on my car window), I was not a Bevanite. And finally, at the start of 2003 I was doing something else, namely writing an academic book on the public memory in twentieth-century Britain. I have always been a historian rather than a biographer; only six of my books have been biographies. I was also an active member of the Lords (dissident Labour), an institution of whose abolition Michael Foot has always been an ardent supporter.

But as soon I began work and began talking to Michael Foot about his career, my doubts immediately dissolved. Having written on Jim Callaghan’s equally fascinating career proved to be a huge stimulus, both in seeing somewhat similar episodes from another perspective, and in finding contrasts and comparisons between two totally different men, each capable of the greatness of spirit to work with someone to whom he was not naturally attuned. The fact that I started from a somewhat different political (and perhaps literary) standpoint from Michael Foot was in itself exciting in trying to examine his principles and his crusades from the outside. Michael himself was typically honourable and honest in recognizing that I came from somewhere else on the Labour continuum, and that in any case I was writing as a detached scholar and lifelong academic. It is characteristic that he has made no effort to read, let alone censor, anything I have written. His view of freedom of expression and interpretation, and the need to pursue them uninhibitedly and audaciously, has been most admirably exemplified in his approach to his own biographer, and I greatly respect that. Even membership of a non-elected House has not, perhaps, been a barrier. And finally, to someone working on the public memory, there is no finer custodian or exemplar of it than Michael Foot, deeply aware, as hardly any contemporary politicians are, of the vital importance of the past – history, legend, memory and myth intertwined – in shaping the present and pointing the way ahead. So writing on Michael Foot has enormously stimulated my earlier interests. As I have moved into my eighth decade, it has given me several new ones: I know far more about Montaigne, Swift or Hazlitt, for example, than I ever did before, and my mind is much the richer for it. In all ways, I have found writing about Michael deeply stimulating. This book has been great fun to write, and it would be nice to think that some readers might find it fun to read. No doubt I shall find out.

Читать дальше