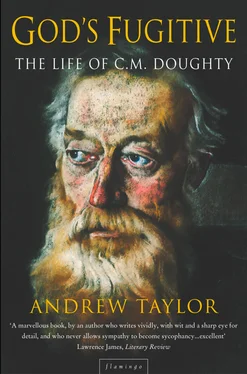

The Life of Charles Montagu Doughty

DEDICATION Dedication Epigraph Foreword Map Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Afterword Keep Reading Bibliography Index Acknowledgements About the Author Notes Author’s Note Praise Also by the Author Copyright About the Publisher

Looking in one direction,

this book is dedicated to

HARRY TAYLOR

and in the other

to

SAM, ABIGAIL AND REBECCA

EPIGRAPH Epigraph Foreword Map Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Afterword Keep Reading Bibliography Index Acknowledgements About the Author Notes Author’s Note Praise Also by the Author Copyright About the Publisher

The traveller must be himself in men’s eyes, a man worthy to live under the bent of God’s heaven, and were it without a religion; he is such who has a clean human heart and longsuffering under his bare shirt: it is enough, and though the way be full of harms, he may travel to the ends of the world.

Travels in Arabia Deserta , i, p. 56

Cover

Title Page GOD’S FUGITIVE The Life of Charles Montagu Doughty

Dedication DEDICATION Dedication Epigraph Foreword Map Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Afterword Keep Reading Bibliography Index Acknowledgements About the Author Notes Author’s Note Praise Also by the Author Copyright About the Publisher Looking in one direction, this book is dedicated to HARRY TAYLOR and in the other to SAM, ABIGAIL AND REBECCA

Epigraph EPIGRAPH Epigraph Foreword Map Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Afterword Keep Reading Bibliography Index Acknowledgements About the Author Notes Author’s Note Praise Also by the Author Copyright About the Publisher The traveller must be himself in men’s eyes, a man worthy to live under the bent of God’s heaven, and were it without a religion; he is such who has a clean human heart and longsuffering under his bare shirt: it is enough, and though the way be full of harms, he may travel to the ends of the world. Travels in Arabia Deserta , i, p. 56

Foreword

Map

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Afterword

Keep Reading

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Notes

Author’s Note

Praise

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Charles Montagu Doughty was the foremost Arabian explorer of his or any other age. His two years of wandering with the bedu through the oasis towns and deserts started a tradition of British exploration and discovery by travellers who acknowledged him as their master, and he returned to England to write one of the greatest and most original travel books.

He was that unlikely adventurer for his day, a man who would not kill – and yet he had strength and passion, and could face the threat of his own death without flinching. As a writer, he believed in his writing and in his vision when nobody else did; turning his back on exploration, he dedicated his life to poetry and struggled singlehandedly to change the direction of English literature. He lived through the greatest revolution in thought the world had ever seen, and spent a lifetime wrestling with his conscience over its consequences.

Among his admirers as an artist were George Bernard Shaw, who found Arabia Deserta inexhaustible. ‘You can open it and dip into it anywhere all the rest of your life,’ he declared. 1 There were F. R. Leavis, Edwin Muir, Wyndham Lewis and, most ardent of all, T. E. Lawrence. Seven Pillars of Wisdom is, in its way, Lawrence’s own homage to Doughty.

And now he is virtually forgotten, his dense and idiosyncratic works valued by antiquarian booksellers and lovers of Arabia, but practically unknown to the readers of a simpler, less painstaking age. The achievement of his travels on foot and by camel seems overshadowed in the days of four-wheel-drive vehicles, helicopters, satellite navigation systems, supply-drops and commercial sponsorship. The great desert journeys are now all in the past. The tradition of Arabian exploration can never be recovered: it is as much a part of history today as the crossing of the Atlantic, or the search for the source of the Nile.

It was Wilfred Thesiger, another great Arabian explorer, who observed that there could never again be a camel-crossing of the desert like his own in the 1940s, or those of the explorers who went before him. ‘I was the last of the Arabian explorers, because afterwards, there were the cars,’ he said. ‘When I made my journeys in Arabia, there was no possibility of travelling in any other way than the way I went. If you could go in a car, it would turn the whole journey into a stunt.’ 2

Thesiger was the last of a line that included Harry St John Philby, father of the Russian spy and the dedicated servant of Ibn Saud, King of Arabia; there was Bertram Thomas, the civil servant who saved up his holidays for his desert expeditions, and became the first European to cross the Empty Quarter; and Gertrude Bell, who travelled to Arabia in the shadow of a disastrous love affair, 3 and demanded that the rulers of Hail treat her like the lady she was and cash her a cheque for £200.

There were the Blunts, Wilfrid and Lady Anne, searching for a romantic Orient which never existed outside the salons of London and Paris; and of course, T. E. Lawrence himself, Lawrence of Arabia, who united the warring tribes just long enough to drive out the Turks and change the face of the Middle East for ever. All of them were passionate, even obsessive, about the desert – and above and before them all stood Charles Montagu Doughty.

The tradition had lasted less than seventy years. Before, there had been adventurers, explorers like Sir Richard Burton or William Gifford Palgrave, who disguised themselves and slipped through Arabia like thieves or spies; after Doughty, with his proud refusal to dissemble, things were never the same again.

Doughty came to Arabia almost by accident, at the end of six years’ wandering through Europe and the Middle East. Initially, he intended to investigate reports of a lost city like Petra, close by the pilgrim road to Mecca; but by the time he sailed away from Jedda two years later, he had dug more deeply into Arabia, lived more closely with the wandering bedu, than any explorer before or since. Thesiger was to collect photographs, Philby tiptoed after tiny birds, reptiles and mammals like some ghastly Angel of Death adding to his collection, and all of them gathered fossils, rocks and ‘specimens’ for the museums at home – but Doughty’s vision embraced an entire civilization.

Everything he did was on a grand scale, and the book he eventually wrote about his travels, which appeared some nine years later, covered nearly 1,200 pages. It was written in a style that mingled Elizabethan and Arabian, the rhythms of the Bible with the precision of a scientific text. And apart from being a staggering work of literary ambition, Travels in Arabia Deserta was, for many of the explorers who followed him, a first introduction to the Arab world.

Читать дальше