The wind howled fiercely over the moorland; a close, thick, wetting rain descended. Chilled to the bone, worn out with long fatigue, sinking to the knees in mire, onward they marched to destruction. One by one the weary peasants fell off from their ranks to sleep, and die in the rain-soaked moor, or to seek some house by the wayside wherein to hide till daybreak. One by one at first, then in gradually increasing numbers, till at last at every shelter that was seen, whole troops left the waning squadrons, and rushed to hide themselves from the ferocity of the tempest. To right and left nought could be descried but the broad expanse of the moor, and the figures of their fellow-rebels, seen dimly through the murky night, plodding onwards through the sinking moss. Those who kept together – a miserable few – often halted to rest themselves, and to allow their lagging comrades to overtake them. Then onward they went again, still hoping for assistance, reinforcement, and supplies; onward again, through the wind, and the rain, and the darkness – onward to their defeat at Pentland, and their scaffold at Edinburgh. 2

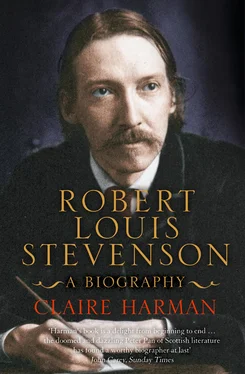

Stevenson’s later description of his apprenticeship as ‘playing the sedulous ape’ to a host of better writers seems needlessly self-mocking when one sees how expert and stylish he was already at the age of fifteen. The prose is very deliberately crafted, with cadences one could almost score, and there is something visionary about his imagination, as if he had personally witnessed the bullets dropping away from Dalzell’s thick buff coat and falling into his boots, seen the flames rising from a Covenanter’s grave on the moor and creeping round the house of his murderer. The boy’s engagement with his subject is so intense as to be almost disturbing. Just after relating the execution of the captured martyrs, he makes an emotional authorial interjection: perhaps it was as well that Hugh McKail’s dying speech to his comrades was drowned out by drums and the jeers of the crowd; these sounds, he wrote, ‘might, when the mortal fight was over, when the river of death was passed, add tenfold sweetness to the hymning of the angels, tenfold peacefulness to the shores which they had reached’. Lewis seems to have been as fervently pious in his mid-teens as in childhood.

It’s hard to imagine how such a performance could have failed to please the boy’s father, but according to a letter in the Balfour archive, the pamphlet was no sooner in type than Thomas Stevenson began to worry about potential criticism of it (from what quarter it is impossible to guess). He had criticised the first drafts himself, as Aunt Jane recalled, who had been at Heriot Row while Lewis was making alterations to the text ‘to please his Father’: ‘[Lewis] had made a story of it, and, by so doing, had spoiled it, in Tom’s opinion – It was printed soon after, just a small number of copies all of which Tom bought in, soon after.’ 3 So the little book’s literary qualities were its downfall; they ‘spoiled’ ‘A Page of History’ to the extent that it couldn’t even be circulated among the aunts, family friends and co-religionists who would have been its natural audience. It must have been hard for the young author to see his first work stillborn. Nor was it the only time Thomas Stevenson pulled this trick, paying for his son’s work to be printed, then censoring it. His solicitude for Lewis has the tinge of monomania, and tallies with what a family friend, Maude Parry, told Sidney Colvin about the relationship after the writer’s death: ‘Stevenson told us that his father had nagged him to an almost inconceivable extent. He thought it the most difficult of all relationships.’ 4

The following year Thomas Stevenson took out a lease on a house right in the heart of Covenanting country, the hamlet of Swanston on the edge of the Pentlands, only a few miles outside Edinburgh. The ‘cottage’ they rented there (in fact a spacious villa, almost as big as Colinton Manse) became their holiday home for the next thirteen years and a winter retreat for Lewis when he was a student. The battlefield of Rullion Green was within walking distance, as was the picturesque ruin of Glencorse Church, and Lewis, now old enough to be left to his own devices, spent days at a time walking the hills, writing and reading – especially adventure stories, caches of which the shepherd John Tod’s son later recalled having found in the whin bushes above the cottage. 5 He was a keen, hardy walker and was able to make a long foot-study of the Pentlands in the years during which Swanston was the family’s second home. This was to become his favourite persona over the next decade or more, the romantic solitary walker, free from responsibility and respectability, watching, listening, picking acquaintance with strangers On the road, falling in with whatever adventures presented themselves.

To true Pentlanders, Lewis Stevenson would have appeared little more than a rich townie weekending on Allermuir, an English-speaking Unionist among terse mutterers of Lallans. No doubt some choice phrases of that dialect were shouted in his direction on the occasion, early in the Stevensons’ tenancy, when the boy barged through a field of sheep and lambs with his Skye terrier Coolin, infuriating the shepherd. 6 Times had changed so rapidly in Scotland that in his late teens Stevenson knew no one of his own generation (certainly not of his class) whose primary language was Scots. ‘Real’ Scotsmen, like Robert Young, the gardener at Swanston, or John Tod the shepherd, or his late Grandfather Balfour, were distant, older figures who presented the paradox of being at once admirable and impossible to emulate. And with the language many temperamental traits and ‘accents of the mind’ were disappearing too, or seemed tantalisingly out of reach, as Stevenson’s loving description of shepherd Tod in his 1887 essay ‘Pastoral’ indicates:

That dread voice of his that shook the hills when he was angry, fell in ordinary talk very pleasantly upon the ear, with a kind of honied, friendly whine, not far off singing, that was eminently Scottish. He laughed not very often, and when he did, with a sudden loud haw-haw, hearty but somehow joyless, like an echo from a rock. His face was permanently set and coloured; ruddy and stiff with weathering; more like a picture than a face [ … ] He spoke in the richest dialect of Scots I ever heard; the words in themselves were a pleasure and often a surprise to me, so that I often came back from one of our patrols with new acquisitions; and this vocabulary he would handle like a master, stalking a little before me, ‘beard on shoulder’, the plaid hanging loosely about him, the yellow staff clapped under his arm, and guiding me uphill by that devious, tactical ascent which seems peculiar to men of his trade. I might count him with the best of talkers; only that talking Scotch and talking English seem incomparable acts. He touched on nothing at least, but he adorned it; when he narrated, the scene was before you; when he spoke (as he did mostly) of his own antique business, the thing took on a colour of romance and curiosity that was surprising. 7

The ‘romance and curiosity’ of Scotsness haunted Stevenson all his life; he never tired of it. But the fact that his own culture could be romantic and curious to him he knew to be an unfortunate state of affairs. His writing about Scotland is therefore strongly melancholic and valedictory, quite unlike the language-revival movements of the following century which sought to resuscitate the culture by creating synthetic Scots. Within 150 years, the literary language waxed, waned and then reappeared again in the form of a sort of composite ghost of itself in the ‘Scottish Renaissance’ of the mid-twentieth century (pioneered by the poet Hugh MacDiarmid). But in the 1860s and ’70s, the language seemed beyond revival, and what Burns had used both naturally and daringly, Stevenson could only lament and pastiche, writing of his later attempts at Scots vernacular verse, ‘if it be not pure, what matters it?’ 8

Читать дальше