The royal party arrived in Cape Town on 17 February to a tumultuous welcome that banished fears of republican hostility. There was a glittering state banquet the same night. Next day, Lascelles wrote home that while he had never attended a more dreary and miserable dinner in thirty years of attending public functions, the Royal Family seemed to enjoy it, especially the princesses. ‘Princess E[lizabeth] is delightfully enthusiastic and interested,’ he noted; ‘she has her grandmother’s passion for punctuality, and, to my delight, goes bounding furiously up the stairs to bolt her parents, when they are more than usually late.’ 43The plan was to bring the British Monarchy into direct contact with every part of the Union – in the words of the tour’s official souvenir – from the seaboard of the Cape and Natal ‘to areas where African tribes live in peace and security under conditions which still suggest the Africa of history.’ 44

The royal party slept in a special ‘White Train’ for a total of thirty-five nights, travelling to the Orange Free State, Basutoland, Natal and the Transvaal, and then to Northern Rhodesia and Bechuanaland. South Africa was a society rigidly divided on racial grounds: but it did not yet have strict apartheid laws, and the royal party met people from different communities, even attending a ‘Coloured Ball’. The King’s daughter attracted particular attention. Africans shouted from the crowds ‘Stay with us!’ and ‘Leave the Princess behind!’ 45The presence of British royalty also aroused keen interest in the small, enclosed white South African world, dominating popular entertainment. At a huge civic ball held in Cape Town the night following their arrival, five thousand guests danced to a fox-trot composed in honour of Elizabeth, called ‘Princess’. The tune accompanied a song which became the catch of the season. ‘Princess, in our opinion,’ went its loyal refrain, ‘You’ll find in our Dominion/Greetings that surely take your breath,/For you have a corner in every heart,/Princess Elizabeth’. 46Elsewhere, there were other musical tributes. At Eshowe, Zulu warriors pounded out the ‘Ngoma Umkosi,’ the Royal Dance before the King. One verse was omitted at the last minute: ‘We hear, O King, your eldest daughter, Princess Elizabeth, is about to give her heart in marriage, and we would like to hear from you who is the man, and when this will be.’ 47On 1st April, close to the end of the tour, the not unwelcome or unhelpful news came through of the death of King George of Greece. Lascelles reported home that while there would be a week’s court mourning in London, no notice at all would be taken ‘by anybody out here because we haven’t any becoming mourning with us – a typical Royal Family compromise!’ 48

At East London, the second city of Cape Province, Elizabeth had to open a graving dock – it was a windy day, and she had to struggle to keep her hat on, her dress down, and her speech from blowing away. 49For much of the trip, however, the princesses’ most demanding duty was to walk behind their parents at ceremonies or sit beside them at displays. It was a long time to be away, on holiday yet constantly on show – and out of touch with ice-bound Britain, where Philip, at his naval base, lectured his students in his naval greatcoat and by candlelight, because of the fuel crisis. According to below-stairs gossip, spread by Bobo MacDonald, who had graduated from children’s nursemaid to become the Princess’s maid and dresser, ‘Elizabeth was very eager for mail throughout the tour, and so was Philip.’ 50She also wrote to other friends. Lord Porchester, for instance, received letters from her wherever she went. She wrote vividly, about the tour and meeting Smuts, but also about home. In one letter she asked about her horse, Maple Leaf. 51

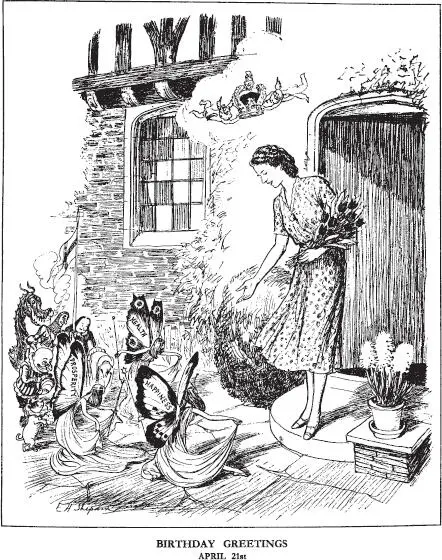

The passivity, however, did not last until the end of the tour. The Royal Family’s departure date was fixed for 24 April. Princess Elizabeth’s twenty-first birthday fell three days earlier – a happy coincidence of timing which enabled the South African government to make it the climax of the visit. It could scarcely have been celebrated on a more elaborate, and extravagant, scale. As a token of the importance Smuts attached to the royal tour, 21 April was declared a public holiday throughout the Union. In addition, the royal birthday was marked by a ceremony, attended by the entire Cabinet, at which the Princess reviewed a large contingent of soldiers, sailors, women’s services, cadets and veterans; by a speech given by the Princess to a ‘youth rally of all races’; by a reception at City Hall in Cape Town; and by yet another ball in the Princess’s honour at which General Smuts presented her with a twenty-one-stone gemstone necklace and a gold key to the city.

The Royal Family made its own most dramatic contribution to the day’s events in the form of a broadcast to the Empire and Commonwealth by Princess Elizabeth, which became the most celebrated of her life. The author was not the Princess, but Sir Alan Lascelles, a straight-backed, hard-bitten courtier, not given to emotionalism – though with a sense of occasion and (as his memoranda and diaries reveal) a lucid, if somewhat old-fashioned, literary style. The speech was both a culmination to the tour, and a prologue for the Princess.

When Princess Elizabeth was consulted in the White Train near Bloemfontein during the preparation of a draft, according to one account, she told her father’s private secretary, ‘It has made me cry’. The effect on many listeners and cinema-goers was much the same as they heard or later watched the solemn young woman making her commitment, like a confirmation or a marriage vow. That her message came from a problematic dominion added to the impact of words which already sounded archaic, and a few years later might have seemed kitsch, yet which seemed strangely to capture the moment. The effect was the more surprising because Lascelles had made no concessions to populism, and had not attempted to write the kind of speech a young woman might have delivered, if the thoughts had been her own.

Punch , 23rd April 1947

‘Although there is none of my father’s subjects, from the oldest to the youngest, whom I do not wish to greet,’ the Princess read from her script, ‘I am thinking especially today of all the young men and women who were born about the same time as myself and have grown up like me in the terrible and glorious years of the Second World War. Will you, the youth of the British family of nations, let me speak on my birthday as your representative?’ She quoted Rupert Brooke. She spoke of the British Empire which had saved the world, and ‘has now to save itself,’ and of making the Commonwealth more full, prosperous and happy. Thus far, her speech belonged alongside other truistic utterances forgettably spoken by royalty when required to address the public. It was the next part that took listeners by surprise. Unexpectedly, she changed tack, launching into what amounted to a personal manifesto, that combined two themes of Sir Henry Marten in his tutorials – the Commonwealth, and the importance of broadcasting:

There is a motto which has been borne by many of my ancestors – a noble motto, “I serve”. Those words were an inspiration to many bygone heirs to the throne when they made their knightly dedication as they came to manhood. I cannot do quite as they did, but through the inventions of science I can do what was not possible for any of them. I can make my solemn act of dedication with a whole Empire listening. I should like to make that dedication now. It is very simple.

Читать дальше