AFTER ELIZABETH

The Death of Elizabeth and the Coming of King James

LEANDA DE LISLE

For Peter,Rupert, Christian and Dominic,my cornerstones .

‘ If you can look into the seeds of time,And say which grain will grow and which will not’ ,

William Shakespeare, Macbeth

COVER

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

EPIGRAPH

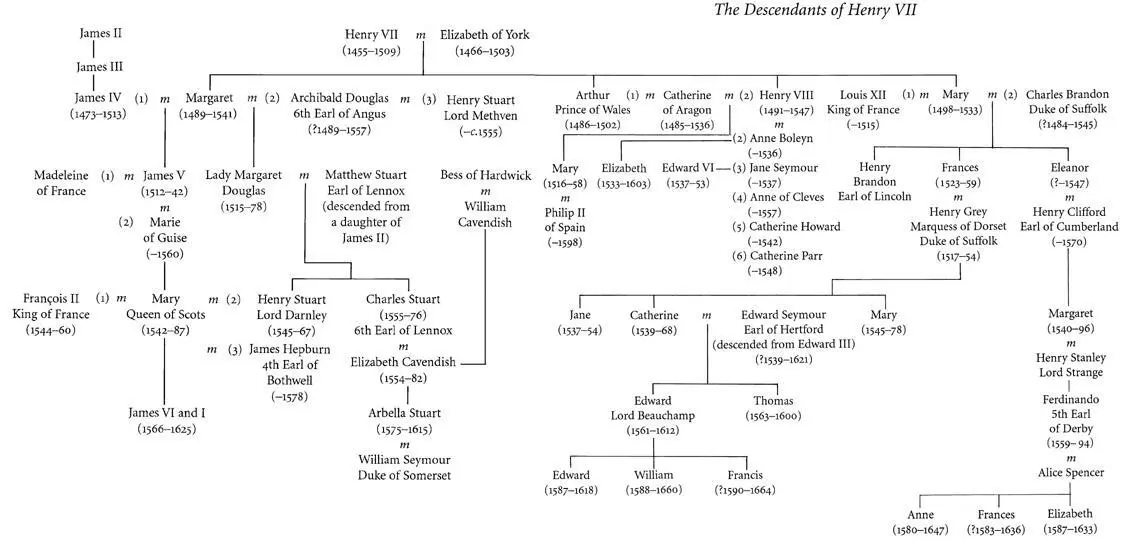

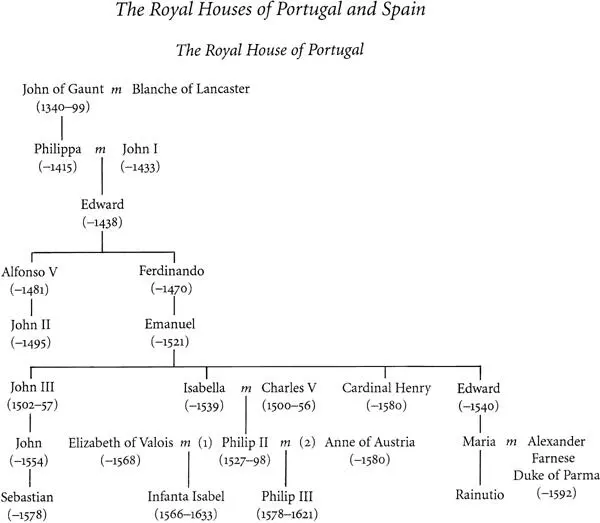

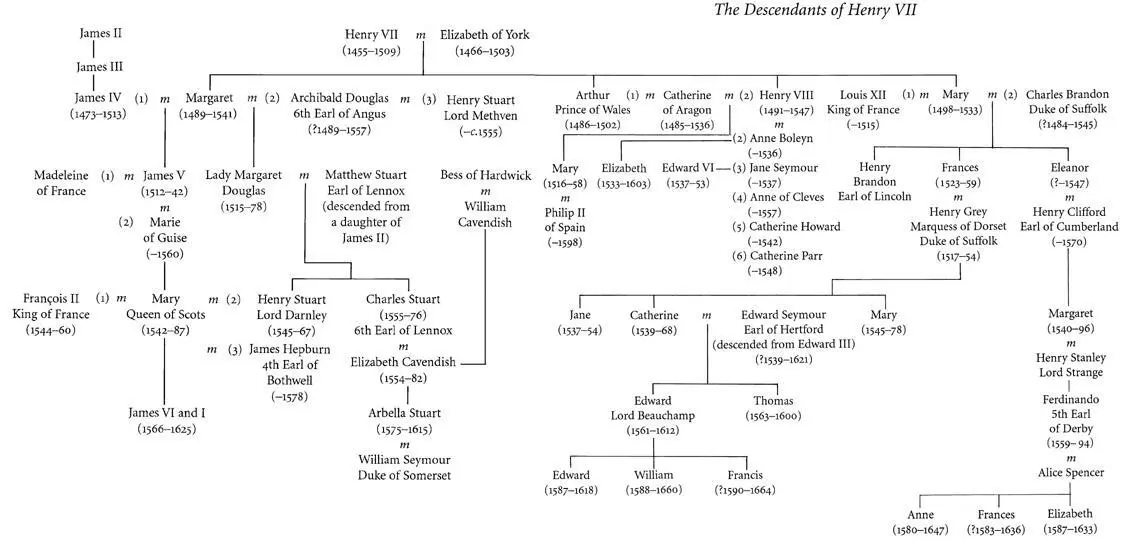

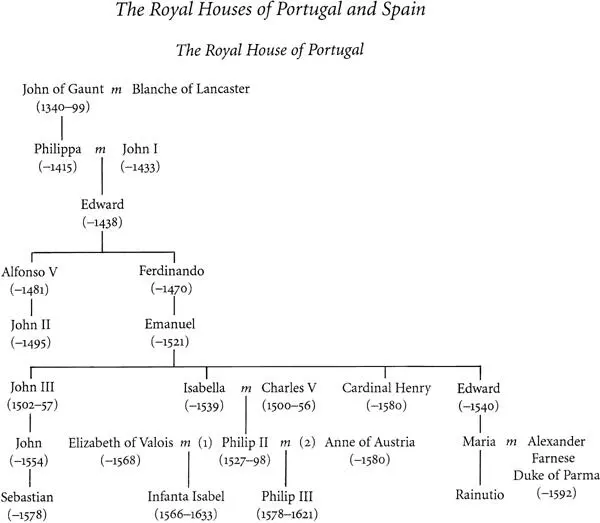

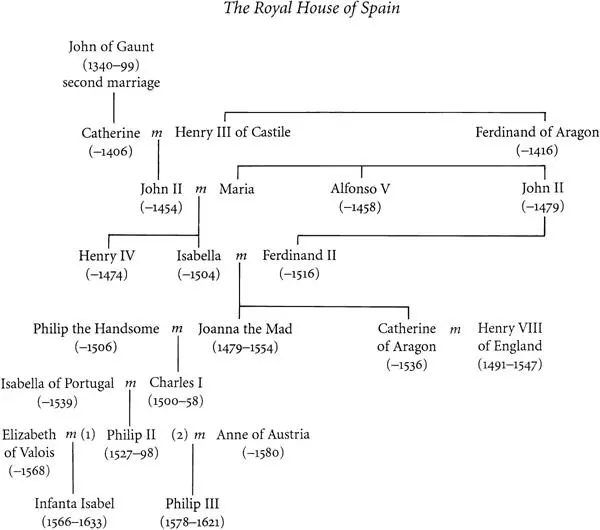

GENEALOGY

MAP

PART ONE

CHAPTER 1 ‘The world waxed old’ The twilight of the Tudor dynasty

CHAPTER 2 ‘A babe crowned in his cradle’ The shaping of the King of Scots

PART TWO

CHAPTER 3 ‘Westward … descended a hideous tempest’ The death of Elizabeth, February–March 1603

CHAPTER 4 ‘Lots were cast upon our land’ The coming of Arthur, March–April 1603

CHAPTER 5 ‘Hope and fear’ Winners and losers, April–May 1603

CHAPTER 6 ‘The beggars have come to town’ Plague and plot in London, May–June 1603

PART THREE

CHAPTER 7 ‘An anointed King’ James and Anna are crowned, July–August 1603

CHAPTER 8 ‘The God of truth and time’ Trial, judgement and the dawn of the Stuart age

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

P.S. IDEAS, INTERVIEWS & FEATURES …

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Q AND A WITH LEANDA DE LISLE

LIFE AT A GLANCE

TOP FIVE, BOTTOM FIVE

A WRITING LIFE

ABOUT THE BOOK

A LETTER TO THE READER BY LEANDA DE LISLE

READ ON

IF YOU LOVED THIS, YOU MIGHT LIKE …

FIND OUT MORE

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

AUTHOR’S NOTE

NOTES

PRAISE

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

The Descendants of Henry VII

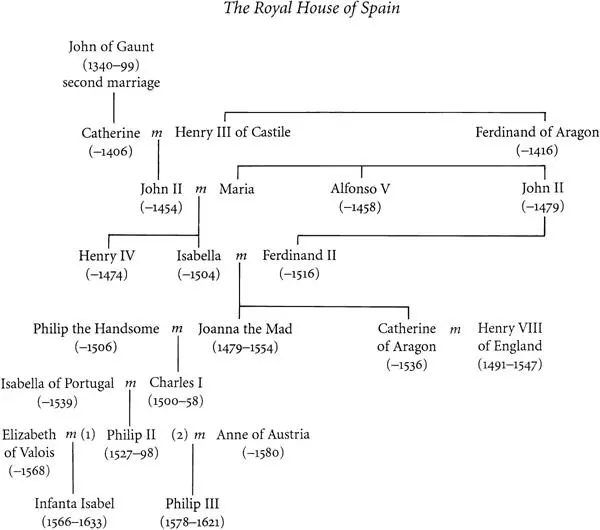

The Royal Houses of Portugal and Spain

The House of Talbot

The House of Cavendish

‘ There are more that look, as it is said,to the rising than to the setting sun ’

Elizabeth I

CHAPTER ONE

‘The world waxed old’

The twilight of the Tudor dynasty

SIR JOHN HARINGTON arrived at Whitehall in December 1602 in time for the twelve-day Christmas celebrations at court. The coming winter season was expected to be a dull one, though the new Comptroller of the Household, Sir Edward Wotton, was trying his best to inject fresh life into it. Dressed from head to toe in white he had laid on dances, bear baiting, plays and gambling. The Secretary of State, Sir Robert Cecil, lost up to £800 a night – an astonishing sum, even for one who, according to popular verse, ruled ‘court and crown’. Behind the scenes, however, courtiers gambled for still higher stakes. Harington observed that Elizabeth I, the last of the Tudors, was sixty-nine and although she appeared in sound health ‘age itself is a sickness’. 1 She could not live forever and after a reign of forty-four years the country was on the eve of change.

To Elizabeth, Harington was ‘that witty fellow my godson’. Courtiers knew him for his invention of the water closet, his translations of classical works, his scurrilous writings on court figures and his mastery of the epigram, which was then the fashionable medium for comment on court life. In the competition for Elizabeth’s favour, however, courtiers were expected to reflect her greatness not only in learning and wit but also in their visual magnificence. They did so by dressing in clothes ‘more sumptuous than the proudest Persian’. A miniature depicts Harington as a smiling man in a cut silk doublet and ruff, his long hair brushed back to show off a jewelled earring that hangs to his shoulder. Even a courtier’s plainest suits were worn with beaver hats and the finest linen shirts, gilded daggers and swords, silk garters and show roses, silk stockings and cloaks. 2

This brilliant world was a small one, though riven by scheming and distrust. ‘Those who live in courts, must mark what they say,’ one of Harington’s epigrams warned, ‘Who lives for ease had better live away.’ 3 Harington, typically, knew everyone at Whitehall that Christmas, either directly or through friends and relations. 4 Elizabeth herself was particularly close to the grandchildren of her aunt Mary Boleyn, known enviously as ‘the tribe of Dan’. The eldest, Lord Hunsdon, was the Lord Chamberlain responsible for the conduct of the court. His sisters, the Countess of Nottingham, and Lady Scrope, were Elizabeth’s most favoured Ladies of the Privy Chamber. But Harington also had royal connections, albeit at one remove. His estate at Kelston in Somerset had been granted to his father’s first wife, Ethelreda, an illegitimate daughter of Henry VIII. When Ethelreda died childless the land had passed to John Harington senior. He remained loyal to Elizabeth when she was imprisoned following a Protestant-backed revolt against her Catholic sister Mary I, named after one of its leaders as Wyatt’s revolt, and when Elizabeth became Queen she rewarded him with office and fortune, making his second wife, Harington’s mother Isabella Markham, a Lady of the Privy Chamber. It was the hope of acquiring such wealth and honour that was the chief attraction of the court.

Harington once described the court as ‘ambition’s puffball’ – a toadstool that fed on vanity and greed, but it was one that had been carefully cultivated by the Tudor monarchy. With no standing army or paid bureaucracy to enforce their will the monarchy had to rely on persuasion. They used Arthurian mythology and courtly displays to capture hearts, while patronage appealed to the more down-to-earth instincts of personal ambition. Elizabeth could grant her powerful subjects the prestige that came with titles and orders; the influence conferred by office in the Church, the military, the administration of government and the law; there were also posts at court or in the royal household. She could bestow wealth with leases on royal lands and palaces, offer special trading licences and monopolies or bequeath the ownership of estates confiscated from traitors. 5 Those who gained most from Elizabeth’s patronage were themselves patrons, acting as conduits for the Queen’s munificence.

Harington and his friends worked hard to ingratiate themselves with the great men at court, often spending years, as he complained, in ‘grinning scoff, watching nights and fawning days’. 6 When a great patron fell from grace a decade of personal and financial investment could be lost. The precise standing of all senior courtiers was therefore tracked and discussed by gossips and intelligencers. Every tiny fluctuation in their fortunes stoked what one observer described as, ‘The court fever of hope and fear that continuously torments those that depend upon great men and their promises.’ 7 The ‘fever’ reached a pitch when the health of the monarch was a cause for concern since their death could mean a complete revolution in government.

Читать дальше