CHAPTER 2 THE RACER: PART ONE

‘He was it. He was the main man who everyone had to beat.’

RON HASLAM

After scoring such a resounding double victory in only his second-ever race meeting, in April 1968 Barry Sheene surprised many people by opting out of racing for a few months. Still unconvinced that racing was the proper career path to follow, he decided to take in a second tour of Europe, this time spannering for a rider called Lewis Young. Young was riding Bultacos, which by now Barry knew inside out, and he wisely came to the conclusion that a season following the Grand Prix circus around Europe would teach him more about the motorcycle racing business than a few weekends spent hurtling round British circuits. It might have seemed at the time an odd move to make, but it proved to be a well-judged one. This time, Barry really laid the foundations for his future career by getting to know all the circuits, the travelling routines and the way of life in the paddock, as well as gaining countless contacts all of whom would play a part in his future. The experience was heady and intoxicating, and by the time he returned to England that autumn not only was he 10kg lighter after eating so sparsely and irregularly, he had also decided to race again. Having seen some of the lesser lights who were competing in the Grands Prix, Barry had become convinced that he could beat most of them.

The year 1969 was Barry Sheene’s first full season of racing, and for the job in hand he had three Bultacos (125, 250 and 350cc), all immaculately prepared by himself and Frank. His Ford Thames van wasn’t quite so immaculate but it was good enough for the job. By the end of it he was being celebrated as the best newcomer of the season, having finished second to and 16 points behind established British rider Chas Mortimer in the 125cc British Championship. ‘I seem to remember that I won the 125 British Championship quite early on that year,’ Mortimer recalled, ‘then I went on to do some Grands Prix while Barry finished off the championship.’

That season very nearly became Sheene’s first and last when his hero and friend Bill Ivy was killed during practice for the East German Grand Prix in July. Sheene was devastated and suffered a massive asthma attack upon hearing the news. He hadn’t had a relapse since leaving school, and he never had another again. He seriously considered packing in the racing game after Bill’s death, but eventually managed to come to terms with the tragedy, as all motorcycle racers must do; it had to be chalked down as an accident and life had to go on. Sheene persisted, and went on to become Bill’s natural successor in the paddocks of the world, the cheeky cockney rebel with a playboy lifestyle and a gift for flamboyancy. Ivy would have been proud of him.

It was his natural flamboyancy that led Sheene to design the most famous crash helmet in motorcycle racing history, and it grabbed lots of attention during the 1969 season. While most other riders wore very basic designs on their helmets, if any at all, Barry had Donald Duck emblazoned on the front of his in a bid to attract attention to himself. It worked, and as the design developed over the years it became the most recognizable in the sport. The completed item featured a black background with gold trimmings, the famous number seven on the sides (more of which later) and, for the first time ever in the sport, the rider’s name on the back. ‘It wasn’t intentional,’ Sheene explained. ‘My helmet had gone away to a chap I knew to be painted and it came back with my name emblazoned on the rear. That’s neat, I thought, and I know I turned many heads when I unveiled it for the first time.’ Over the next few decades it became almost compulsory for riders to have their names on the backs of their helmets, and Barry claimed he was the originator of the fashion.

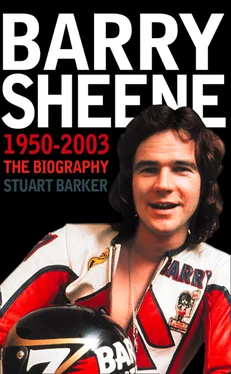

And his fashion sense didn’t stop at helmet designs; he also helped instigate the long-overdue decline in the use of all-black leathers which had so tarnished the image of motorcycle racing. In the twenty-first century motorcycle racing is one of the most colourful sports on the calendar, but it wasn’t always the case, far from it in fact, and Sheene played a large part in the technicolour transformation. In 1972 he ordered a set of white leathers, again largely as a gimmick to get noticed but also as a way of improving the sport’s then drab, greasy image of rough men in black leathers riding noisy, smelly motorbikes. He wasn’t the first rider to brighten up the sport, however, and not everyone was blown away by his garb, as Chas Mortimer testified. ‘I don’t particularly remember Barry’s Donald Duck helmet and white leathers standing out in those days. I mean, I had white leathers then too. Rod Scivyer was the first person to wear them in about 1967 or 1968.’ Sheene would later ditch the white colour scheme believing it was a step too far, but he would go on to wear other brightly coloured leathers such as the famous blue and white Suzuki garments and the even more famous red and black Texaco outfit.

With the trauma of Bill Ivy’s death behind him, Sheene set about preparing for the 1970 season with a team set-up and determination as yet unseen. The icing on the cake was the purchase of an ex-factory 125cc Suzuki from retired rider Stuart Graham. It cost a whopping £2,000, which was an enormous sum at the time and certainly out of Barry’s reach without the help of his dad. Barry used every penny he had to secure the bike – he was still driving a lorry for up to 14 hours a day to raise funds – and borrowed the rest from Frank, though he insisted he paid every penny back.

He made a point of letting everyone know that he repaid his father because he had always been acutely aware of the perception that he was born with a silver spoon in his mouth when it came to racing. After all, he’d had two factory Bultacos for his first outing, a world-class tuner in his dad and, through his father’s connections, advice from some of the best riders in the world. Ron Haslam, who began to challenge Barry’s supremacy on the domestic scene in the mid-seventies, recalled Barry’s machinery advantage. ‘He was it. He was the main man who everyone had to beat. I was helping my brother [Terry Haslam, who was killed racing in 1974] who was beating him sometimes even though he didn’t have all the tackle Sheene had. Sheene had factory bikes from the start so it was such a big thing for my brother to beat him on lesser machinery.’ Ron himself struggled against Barry on ‘lesser machinery’ on many occasions; whenever he came out on top it was always sweetly satisfying. ‘Sheene was like any rider in that he thought he was the best, as I did. You have to think that. He had superior equipment but he was still beatable, and I always believed I could beat him.’

Barry knew that his little ten-speed Suzuki was fast enough to run at World Championship level, and that’s exactly where he intended to be for his third year of racing – a feat almost unheard of in the modern Grand Prix world. Having won his first race on the Suzuki at Mallory Park, Sheene became so dominant on it in Britain that year that he later left it at home and raced the Bultaco instead. It appeared to be an extremely sporting gesture but was, in essence, more of a shrewd financial move: the Suzuki was much too precious to risk in British rounds when it wasn’t needed, and Barry couldn’t afford to be faced with astronomical spares bills should he crash the bike or damage it in any way. The Suzuki was, however, the weapon of choice for the last Grand Prix of the season in Spain, which also happened to be Barry’s first. He had already wrapped up the 1970 125cc British Championship for his first-ever title and decided he needed to up the stakes as far as the competition went if he was to continue on his steep learning curve.

Читать дальше