COPYRIGHT

HarperNonFiction

A division of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2004.

This edition first published by HarperCollins Publishers in 2005

Copyright © Neal Bascomb 2004

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Neal Bascomb asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollins Publishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007173723

Ebook Edition © MAY 2017 ISBN: 9780007382989

Version: 2017-05-11

DEDICATION

To Diane

AUTHOR’S NOTE

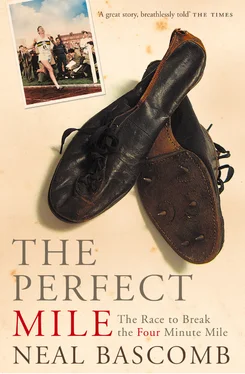

When an author sets out to investigate a legend, and there are few stories as legendary in sport as the pursuit of the four-minute mile, it is initially difficult to see the heroes around whom events unfolded as true flesh-and-blood individuals. Myth tends to wrap its arms around fact, and memory finds a comfortable groove and stays the course. What makes these individuals so interesting – their doubts, vulnerabilities, and failures – is often airbrushed out, and their victories characterised as faits accomplis. But true heroes are never as unalloyed as they first appear (thank goodness). We should admire them all the more for this fact.

Getting past the panegyrics that populate this history has been the real pleasure behind my research. No doubt there have been some very fine articles written about this story, but only by interviewing the principals – Roger Bannister, John Landy, and Wes Santee – and their close friends at the time does one do justice to the depth of this story. Their generosity in this regard has been without measure. These interviews, coupled with contemporaneous newspaper and magazine articles as well as memoir accounts by several individuals involved in the events, serve as the basis of The Perfect Mile. With this material, the story almost wrote itself.

I have included collective references for those interested in knowing the sources behind particular conversations and scenes. No dialogue in this book was manufactured; it is either a direct quote from a secondary resource or from an interview. That said, half a century has passed since this story occurred. On some occasions, dialogue is represented as the best recollection of what was in all probability said. Furthermore, memory has its faults, and in those situations where interview subjects contradicted one another I almost always went with what the principal recollected. In those instances when contemporaneous sources (mainly newspaper articles) did not correspond with memory, I primarily went with the former, particularly when there were several sources indicating the same facts. Having inhabited this world for the past eighteen months, aswim in paper and interview tapes, I feel I have been a fairly accurate judge of the events as they happened. I hope that I have served the history of these heroes well.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Author’s Note

Prologue

PART I

A Reason to Run

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

PART II

The Barrier

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

PART III

The Perfect Mile

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Epilogue

References

Acknowledgements

Other Books By

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone ,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: ‘Hold on!’

Rudyard Kipling, ‘If …’

‘How did he know he would not die?’ a Frenchman asked of the first runner to break the four-minute mile. Half a century ago the ambition to achieve that goal equalled scaling Everest or sailing alone around the world. Most people considered running four laps of the track in four minutes to be beyond the limits of human speed. It was foolhardy and possibly dangerous to attempt. Some thought that rather than a lifetime of glory, honour, and fortune, a hearse would be waiting for the first man to accomplish the feat.

The four-minute mile: this was the barrier, both physical and psychological, that begged to be broken. The number had a certain mathematical elegance. As one writer explained, the figure ‘seemed so perfectly round – four laps, four quarter miles, four-point-oh-oh minutes – that it seemed God himself had established it as man’s limit’. Under four minutes: the place had the mysterious and heroic resonance of reaching sport’s Valhalla. For decades the world’s best middle-distance runners tried and failed. They came to within a second or so, but that was as close as they were able to get. Attempt after spirited attempt proved futile. Each effort was like a stone added to a wall that looked increasingly impossible to breach.

The four-minute mile had a fascination beyond its mathematical roundness and assumed impossibility. Running the mile was an art form in itself. The distance, unlike the 100-yard sprint or marathon, required a balance of speed and stamina. The person to break that barrier would have to be fast, diligently trained, and supremely aware of his body, so that he would cross the finish line just at the point of complete exhaustion. Further, the four-minute mile had to be won alone. There could be no team-mates to blame, no coach during half-time to inspire a comeback. One might hide behind the excuses of cold weather, an unkind wind, a slow track, or jostling competition, but ultimately, these obstacles had to be defied. Winning a foot race, particularly one waged against the clock, was a battle with oneself, over oneself.

In August 1952 the battle commenced. Three young men in their early twenties set out to be the first to break the barrier. One of them was Wes Santee, the ‘Dizzy Dean of the Cinders’. Santee was a natural athlete, the son of a Kansas ranch hand, born to run fast. He amazed crowds with his running feats, basked in the publicity, and was the first to announce his intention of running the mile in four minutes. ‘He just flat believed he was better than anybody else,’ said one sportswriter. Few knew that running was his escape from a brutal childhood.

Читать дальше