Then there was John Landy, the Australian who trained harder than anyone else and had the weight of a nation’s expectations on his shoulders. The mile for Landy was more aesthetic achievement than foot race. He said, ‘I’d rather lose a 3:58 mile than win one in 4:10.’ Landy ran night and day, across fields, through woods, up sand dunes, along the beach in knee-deep surf. Running revealed to him a self-discipline he never knew he possessed.

And finally there was Roger Bannister, the English medical student who epitomised the ideal of the amateur athlete in a world being overrun by professionals and the commercialisation of sport. For Bannister the four-minute mile was ‘a challenge of the human spirit’, but one to be realised with a calculated plan. It required scientific experiments, the wisdom of a man who knew great suffering, and a magnificent finishing kick.

All three runners endured thousands of hours of training to shape their bodies and minds. They ran more miles in a year than many of us walk in a lifetime. They spent a large part of their youths struggling for breath. They trained week after week to the point of collapse, all to shave off a second, maybe two, during a mile race – the time it takes to snap one’s fingers and register the sound. There were sleepless nights, training sessions in rain, sleet, snow, and scorching heat. There were times when they wanted to go out for a beer or a date yet knew they couldn’t. They understood that life was somehow different for them, that idle happiness would elude them. If they weren’t training or racing or gathering the will required for these, they were trying not to think about training and racing at all.

In 1953 and 1954, as Santee, Landy, and Bannister attacked the four-minute barrier, getting closer with every passing month, their stories were splashed across the front pages of newspapers around the world, alongside headlines of the Korean War, the atomic arms race, Queen Elizabeth’s coronation, and Edmund Hillary’s climb towards the world’s rooftop. Their performances outdrew golf majors, Ashes Tests, horse derbies, football and rugby matches, and baseball pennant races. Stanley Matthews, Ben Hogan, Rocky Marciano, Mike Hawthorn and Surrey County Cricket Club were often in the shadows of the three runners, whose achievements attracted media attention to athletics that has never been equalled. For weeks in advance of every race the headlines heralded an impending break in the barrier: ‘Landy Likely to Achieve Impossible!’; ‘Bannister Gets Chance of 4-Minute Mile!’; ‘Santee Admits Getting Closer to Phantom Mile’. Articles dissected track conditions and the latest weather forecasts. Millions around the world followed every attempt. Whenever any of the runners failed – and there were many failures – he was criticised for coming up short, for not having what it took. Each such episode only motivated the others to try harder.

They fought on, reluctant heroes whose ambition was fuelled by a desire to achieve the goal and to be the best. They had fame, undeniably, but of the three men only Santee enjoyed the publicity, and that proved to be more of a burden than an advantage. As for riches, financial reward was hardly a factor. They were all amateurs. They had to scrape around for pocket change, relying on their hosts at races for decent room and board. The prize for winning a meet was usually a watch or a small trophy. At that time, the dawn of television, when amateur sport was losing its innocence to the new spirit of win-at-any-cost, these three strove only for the sake of the attempt. The reward was in the effort.

After four soul-crushing laps around the track, one of the three finally breasted the tape in 3:59.4, but the race did not end there. The barrier was broken, and a media maelstrom descended on the victor, yet the ultimate question remained: who would be the best when they toed the starting line together?

The answer came in the perfect mile, a race no longer fought against the clock, rather against one another. It was won with a terrific burst around the final bend in front of an audience that spanned the globe.

If sport, as a chronicler of this battle once said, is a ‘tapestry of alternating triumph and tragedy’, then the first thread of this story begins with tragedy. It occurred in a race 120 yards short of a mile, at the Olympic 1,500m final in Helsinki, Finland, almost two years to the day before the greatest of triumphs.

I

A REASON TO RUN

1

I have now learned better than to have my races dictated by the public and the press, so I did not throw away a certain championship merely to amuse the crowd and be spectacular.

Jack Lovelock, 1,500m gold medallist, 1936 Olympics

On 16 July 1952 at Motspur Park, south London, two men were running around a black cinder track in singlets and shorts. The stands were empty, and only a scattering of people watched former Cambridge miler Ronnie Williams as he tried to stay even with Roger Bannister, who was tearing down the straight. It was inadequate to describe Bannister as simply ‘running’: eating up yards at a rate of seven per second, he was moving too fast to call it running. His pacesetter for the first half of the time trial, Chris Chataway, had been exhausted, and the only reason Williams hadn’t folded was that all he needed to do was maintain the pace for a lap and a half. What most distinguished Bannister was his stride. Daily Mail journalist Terry O’Connor tried to describe it: ‘Bannister had terrific grace, a terrific long stride, he seemed to ooze power. It was as if the Greeks had come back and brought to show you what the true Olympic runner was like.’

Bannister was tall – six foot one – and slender of limb. He had a chest like an engine block and long arms that moved like pistons. He flowed over the track, the very picture of economy of motion. Some said he could have walked a tightrope as easily, so balanced and even was his foot placement. There was no jarring shift of gears when he accelerated, as he did in the last stage of the three-quarter-mile time trial, only a quiet, even increase in tempo. Bannister loved that moment of acceleration at the end of a race, when he drew upon the strength of leg, lung, and will to surge ahead. Yes, Bannister ran, but it was so much more than that.

As he sped to the finish with Williams at his heels, Bannister’s friend Norris McWhirter prepared to take the time on the sidelines. He held his thumb firmly on the stopwatch button, knowing that because of the thumb’s fleshiness, having it poised only lightly added a tenth of a second at least. Bannister shot across the finish; McWhirter punched the button. When he read the time, he gasped.

Norris and his twin brother Ross had been close to Bannister since their days at Oxford University. They were three years older than the miler, having served in the Royal Navy during the Second World War, but they had been Blues together in the university’s athletic club. Norris had always known there was something special about Roger. Once, during an Italian tour with the Achilles Club (the combined Oxford and Cambridge athletic club), which Bannister had dominated, McWhirter had looked over with amazement at his friend sleeping on the floor of a train heading to Florence and thought, ‘There lies the body that perhaps one day will prove itself to possess a known physical ability beyond that of any of the one billion other men on earth.’ Sure enough, as McWhirter stared down at his stopwatch that July afternoon, he could hardly believe the time: Bannister had run three-quarters of a mile in 2:52.9, four seconds faster than the world record held by the great Swedish miler Arne Andersson.

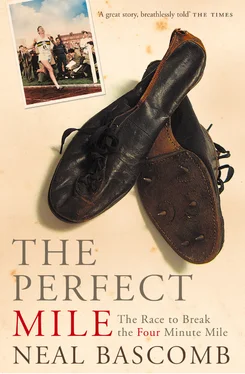

After gathering his breath, Bannister walked over to see what the stopwatch read. Cinders clung to his running spikes. At the time, athletics shoes were simply a couple of pieces of thin leather that moulded themselves so tightly to the feet when the laces were drawn that one could see the ridges of the toes. The soles were embedded with six or more half-inch-long steel spikes for traction. Running surfaces, too, had advanced very little over the years. They were mostly oval dirt strips layered on top with ash cinders that were taken from boilers at coal-fired electricity plants. Track quality depended on how well the cinders were maintained, since in the sun they became loose and tended to blow away, and when it rained the track turned to muck. Motspur Park’s track benefited from the country’s best groundskeeper, and it was one of the fastest, which was why Bannister had chosen it for this time trial.

Читать дальше