The waiter landed, his grin turning to a frown, wondering where his victim had gone. Then, shrugging, he veered around and went back into the restaurant, slamming the door behind him.

Gurl rested her hand on the pavement. The mouse crawled out from the safety of her sleeve and ran into the darkness. “Bye,” said Gurl, watching as it disappeared through a hole in the brick. She supposed she was lucky that the waiter hadn’t seen her, but then again, she was not the type of girl that people noticed—she was too thin, too pale, too quiet. Sometimes people looked right through her as if she weren’t there at all, their eyes sliding off her as if she were made of something too slippery to see. Nobody, nowhere. When she was little, it made her feel lonely. Now she only felt grateful.

She stretched and walked over to the Dumpster. After throwing open the lid, she dug around until she found what she was looking for: four foil-wrapped packages of leftovers. Ravioli, lasagne, salad and a huge hunk of gooey chocolate cake.

If only the other kids from Hope House for the Homeless and Hopeless were here, watching, maybe they wouldn’t think so little of her. But they, like everyone else, believed flying was their ticket to fame and fortune, and thought Gurl was horribly afflicted, maybe even contagious. Mrs Terwiliger, the matron of Hope House, had taken her to a specialist once. First he thumped at her knees with a rubber mallet to check her reflexes. He had her breathe in and out very quickly, hyperventilating, to see if the added oxygen might lift her off the floor like a soap bubble. Then he strapped her into a white quilted jacket with huge feather wings and had her run around the office flapping her arms. Finally, he said: “Not everyone can, you know, and most don’t do it well. In any case, it’s nothing to be ashamed of.” As a consolation, he gave Gurl a red and white beanie with a propeller on the top. Mrs Terwiliger told the other kids that people had different talents and they should celebrate them all. “Leadfoot!” the kids yelled as soon as Mrs Terwiliger left the room. “Freak!”

Gurl smiled bitterly to herself. If they were such big deals, why hadn’t they noticed the broken lock? Why hadn’t they thought to sneak out of Hope House at night? Why weren’t they having dinner at Luigi’s? No, this was hers and hers alone. “No man is an island,” Mrs Terwiliger had told her. “One must learn to get along.” But this sparkling city was an island and it got along fine, didn’t it?

Just as she plucked up a pocket of ravioli with her fingers, she heard a sound, one she had heard only on TV.

“Meow.”

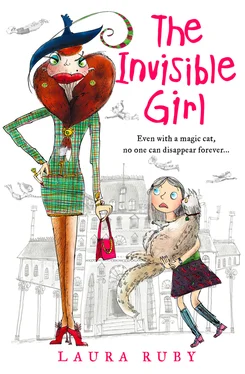

She turned, sure that someone was playing a trick on her. But it was no trick. A cat, as plush and grey as the sky above, padded down the alleyway and sat a few feet from her.

Gurl dropped her ravioli, gaping. She’d seen pictures of cats in books and magazines, of course, but Gurl couldn’t imagine where this one came from. Perhaps it was lost? But how could it be? Nobody let a cat outside; they could get hurt or sick or worse. Plus, there was the matter of people’s regular pets: birds. If people saw a cat, especially without a leash, they’d call the police. What if it attacked an old lady’s budgie or a businessman’s parrot?

The cat regarded her with queer green eyes that glowed in the dark of the alley. “Who belongs to you?” Gurl murmured. Cats chose their owners rather than the other way round; everyone knew that. This cat surely had an owner, someone who liked exotic animals, someone who worked in a zoo maybe. Gurl glanced around at the buildings that rose along either side of the alley. There were lights in some of the windows, but Gurl saw no worried faces in them, heard no frantic calls.

“Meow,” the cat said and took a few steps closer.

“Hey,” said Gurl. “Are you hungry?” She looked at the food in the packages and nudged the one with the lasagne. The cat sniffed, then began to eat in big gulps.

“You are hungry, aren’t you?” Gurl said. “Well, you and me both.” Keeping her eyes on the cat, she reached out and grabbed the package containing cake. Gurl ate like the cat did, in huge greedy bites.

The cat finished everything, right down to the noodles. Then it did something totally unexpected. It walked over to Gurl, reached up with a grey paw and patted Gurl’s cheek, once, twice, three times. Gurl’s eyes opened wide. “No, no, no!” she said. “I can’t take care of you! I’m just an orphan.”

“Meow,” said the cat. It yawned, climbed into her lap and began to make an odd rumbling sound. She’s purring , thought Gurl, who had read about it but never experienced it.

Gurl stared down at the cat. What was she supposed to do now? Where would she keep it? What would she feed it? She shifted her weight and her arm brushed against the cat’s leg. So soft. Hesitantly, Gurl ran a gentle finger between the cat’s ears, the way she would pet a friendly bird. The cat closed its eyes and sighed, pressing its head into her palm.

Just then, the back door of the restaurant flew open and the cat sprang from Gurl’s lap. The waiter marched out the open door carrying another bag of garbage.

“Whoa!” he said. Gurl froze, wishing with all her being that she was nothing more than one of the bricks in the wall. A queer shiver went through her.

But the waiter didn’t even glance in her direction. With his foot, he prodded the opened packages of food. Then he saw the cat standing there, back arched and tail spiked. “What the heck? Where did you come from?”

“Meow,” the cat said.

“Meow is right,” said the waiter. “Here, kitty.”

Since she was so close to him, Gurl could see that his brown eyes were hard and shiny, his smile cold. But why wasn’t he looking at her? Why was he acting as if he couldn’t see her? She was sitting right in front of him, right out in the open! But maybe he was just ignoring her like everyone else. The thought made her angry and she reached out for the cat.

What was wrong with her hands?

She could see them, but just barely. It was as if she were wearing gloves exactly the colours and textures of the alley itself: the black of the pavement, the red of the brick, the pink and white of the graffiti. And when she moved them, they changed to match the background. She touched her face, feeling the heat of her skin beneath her fingertips. If her hands looked like this, what did her face look like?

The waiter bent towards the cat. “Come on now,” he said. “I know someone who’d pay a lot of money to get a load of you.” He lunged for the cat, grabbing it by its front paws. The cat howled. “Shut up, you stupid thing,” the waiter said. The animal hissed, clawing with its back legs.

“Ow!” the waiter yelled, but didn’t let go. Carrying the wildly gyrating cat, he took one huge leap over to a garbage can on the other side of the alley and threw the cat inside. He quickly slammed the cover down and held it. The garbage can bucked and bounced, and the waiter kicked it. “Shut up!” he yelled.

Gurl was furious, but she didn’t know what to do. The waiter wasn’t big, but he was probably stronger than she was. And he could fly, even if he couldn’t do it that well. She unfolded her legs and saw they were exactly like her hands, nearly invisible. If he couldn’t see her, then…

The waiter kicked the garbage can again and the terrified mewls of the cat were too much for Gurl to bear. Though she had never done anything like it before, though she thought her heart would burst like a water balloon, she crept behind the waiter. Grabbing the waistband of his trousers, she yanked upward as hard as she could.

The waiter never flew higher than he did that moment and never would again. Gurl popped the lid off the garbage can. The cat vaulted into her arms, instantly becoming the colour of the air, the colour of nothing. The two of them, Gurl and cat, raced from the alley, just as if they had wings of their own.

Читать дальше