England, Wales and Scotland are divided into 85 counties or shires (England 40, Wales 12, Scotland 33) most of which have persisted with few changes of boundary for more than a thousand years. These years have seen vast changes and some of the counties appear to-day anomalous in a modern world—small, sparsely populated, and poor—but, notwithstanding, intensely proud of their history and tradition and jealous of their ancient rights and privileges. Others have become, with vastly increased populations, too unwieldy and have been divided, so that there are now in England 50 Administrative Counties, making a total for Britain, without the Isle of Man, of 95 Administrative Counties, not including the large towns and cities which are County Boroughs having the status of counties. It would be interesting to know how many of the 45,000,000 people of Britain can lay claim to have set foot in each of the 95 counties. There are whole counties so far off the beaten track that not a man in a thousand has visited them or knows anything of the conditions of life in them, often so greatly different from his home area. How many, for example, know the Shetlands where the midwinter sun at noon does not rise more than six degrees above the horizon but where it is possible to read at midnight in summer without artificial light? If one liked to make the test more severe and ask how many of the 45,000,000 have visited every one of the inhabited islands which make up the British Isles it is most probable that the answer would be—none.

All this is intended to suggest the remoteness, the inaccessibility and the generally unknown character of so many parts of what, if one is content to think merely in terms of square miles and average density of population, is a small and very densely peopled country. So much of it is, indeed, a terra incognita even to the well-travelled minority. To the new naturalist there is much to be explored. It may be that to find a new species of plant or animal not yet described would be an event of unlikely occurrence, but there are many areas where the vegetation has never been mapped or described, where the changing balance of plant and animal life is waiting to be observed and recorded for the first time and where the explanation of observed changes is still a matter of guesswork. Some of the unexplained features are matters of the highest economic importance—the changing character of hill pastures, the new plant relationships created by afforestation and the introduction of foreign trees are some that spring to mind—and all are pregnant with possible scientific results.

Such are the opportunities awaiting the field observer. He has in his homeland what is in many respects a museum model illustrating the evolution of the world as a whole. For the great variety of environments is the outward and visible reflection of a long and complex geological history. Each of the great ages in the earth’s evolution has left its mark on these islands; rocks laid down in all the great periods of geological time are to be found represented in the British Isles.

It thus becomes the purpose of this book to trace the geological evolution of our homeland—to trace, step by step, the building of the British Isles. By this means we are able to understand the structure or the build of its contrasted regions. We are, in fact, attempting to understand the structure and the development of the stage upon which the drama of British natural history is played. In studying the broader aspects we need to consider the British Isles as a whole but, since so many of the books in this series consider primarily the island of Britain—that is England, Wales and Scotland—with its associated smaller islands, we shall consider in more detail and draw most of our examples from it. In tracing the evolution of the structure of the country and of its physical features we are, in fact, attempting to visualise the long history which lies behind the basal elements in its scenery—mountain and plain, hill and dale—recognising at the same time that the intimate details of that scenery are the work of man and lie outside the scope of this volume.

HIGHLAND BRITAIN AND LOWLAND BRITAIN

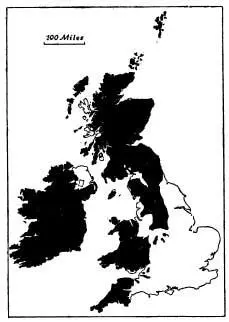

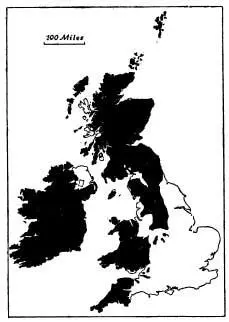

SIR HALFORD MACKINDER in his now classic book, Britain and the British Seas, published in 1902, made a simple yet fundamental distinction between two roughly equal halves of the island of Britain. If one draws a line approximately from the mouth of the Tees to the mouth of the Exe it will be found that all the main hill masses and mountains lie to the north and west, the major stretches of plain and lowland to the south and east. To the north and west lies Highland Britain, to the south and east lies Lowland Britain. There is rarely, in nature, a sharp line between two such regions but rather does the one fade gradually into the other. This is true in Britain; nevertheless it is possible to draw a line with some accuracy and this has been done in Fig. 1.

In Highland Britain the dominant character of the country is upland. There are large and continuous stretches more than a thousand feet above sea level; plains and valleys occur but they are of limited extent and tend to form interruptions in the general upland character of the country as a whole. In some places are rugged mountains and even at lower levels crags of rock may appear at the surface. Even where the rocks do not thus appear at the surface itself they are often but thinly covered by poor stony soils, whilst the many steep slopes as well as the broken character of the relief may make farming difficult. On the whole man has sought out for himself the more sheltered situations for his farms, his villages and his towns. They nestle in valleys ; they flourish and spread only where the larger tracts of flat land or more fertile soil occur or where man has been attracted to otherwise inhospitable surroundings by stores of mineral wealth. The higher, poorer, wetter or less accessible parts of Highland Britain have been left largely to nature. There are vast stretches of moorland, some of it covering land from which the original forest cover has been removed, as well as mosses and bogs, scrub woodland and forests. We may summarise the position by saying that in Highland Britain human settlement is essentially discontinuous: the cultivated areas occupy valleys and plains separated by large expanses of uncultivated hill lands. This is well shown in the aerial view of a Lakeland valley in Plate I.

Lowland Britain offers a striking contrast in many ways. Though so much less rugged, there are few parts where level land is uninterrupted by hills and such true plains as do exist are to a considerable degree the result of man’s handiwork—as the large stretch of the drained fenlands of eastern England bears witness. Lowland Britain is best described as an undulating lowland where lines of low hills are separated by broad open valleys and where “islands” of upland break the monotony of the more level areas.

FIG. 1.—Highland Britain and Lowland Britain

Even the highest of the hills scarcely ever exceed a thousand feet above sea level, though many of the ridges reach 600 or 700 feet. The environment is kinder ; the soils tend to be deeper and richer, there are few steep slopes to interrupt cultivation and plough lands are to be found right to the tops of the hills. There is little to hinder man’s use of the whole: human settlement is essentially continuous and the cultivated land of one parish merges into that of the next. Villages and towns are closely and evenly scattered ; their siting has sometimes been dictated by convenience of a water supply, sometimes by situation on a natural routeway, sometimes just to maintain an even spacing of settlements. It follows that the greater part of Lowland Britain is occupied by farmland—by “cultivated” or “improved” land, which includes both plough and grass land—and that such moorlands, heaths, “wastes” and other unimproved lands as occur, do so as islands interrupting the otherwise continuous farmland and coinciding with patches of poorer soils.

Читать дальше