Felix started.

‘I see what you’re after at last,’ he said. ‘He walked up the drive twice.’

‘Of course he did. He walked up first with you to leave the cask. He walked up the second time with the empty dray to get it. If the impressions were really made by Watty that seems quite certain.’

‘But what on earth would Watty want with the cask? He could not know there was money in it.’

‘Probably not, but he must have guessed it held something valuable.’

‘Inspector, you overwhelm me with delight. If he took the cask it will surely be easy to trace it.’

‘It may or it may not. Question is, are we sure he was acting for himself.’

‘Who else?’

‘What about your French friend? You don’t know whom he may have written to. You don’t know that all your actions with the cask may not have been watched.’

‘Oh, don’t make things worse than they are. Trace this Watty, won’t you?’

‘Of course we will, but it may not be so easy as you seem to think. At the same time there are two other points, both of which seem to show he was at least alone.’

‘Yes?’

‘The first is the watcher in the lane. That was almost certainly the man who walked twice up your drive. I told you I found his footmarks at three points along it. One was near your little gate, close beside and pointing to the hedge, showing he was standing there. That was at the very point my man saw the watcher.

‘The second point concerns the horse and dray, and this is what leads me to believe the watcher was really Watty. If Watty was listening up the lane where were these? If he had a companion the latter would doubtless have walked them up and down the road. But if he was alone they must have been hidden somewhere while he made his investigations. I’ve been over most of the roads immediately surrounding, and on my fourth shot—towards the north, as I already told you—I found the place. It is fairly clear what took place. On leaving the cask he had evidently driven along the road until he found a gate that did not lead to a house. It was, as I said, that of a field. The marks there are unmistakable. He led the dray in behind the hedge and tied the horse to a tree. Then he came back to reconnoitre and heard you going out. He must have immediately returned and brought the dray, got the cask, and cleared out, and I imagine he was not many minutes gone before my man Walker returned. What do you think of that for a working theory?’

‘I think it’s conclusive. Absolutely conclusive. And that explains the queer-shaped ladder.’

‘Eh, what? What’s that you say?’

‘It must have been the gangway business for loading barrels on the dray. I saw one hooked on below the deck.’

Burnley smote his thigh a mighty slap.

‘One for you, Mr Felix,’ he cried, ‘one for you, sir. I never thought of it. That points to Watty again.’

‘Inspector, let me congratulate you. You have got evidence that makes the thing a practical certainty.’

‘I think it’s a true bill. And now, sir, I must be getting back to the Yard.’ Burnley hesitated and then went on: ‘I am extremely sorry and I’m afraid you won’t like it, but I shall be straight with you and tell you I cannot—I simply dare not—leave you without some kind of police supervision until this cask business is cleared up. But I give you my word you shall not be annoyed.’

Felix smiled.

‘That’s all right. You do your duty. The only thing I ask you is to let me know how you get on.’

‘I hope we’ll have some news for you later in the day.’

It was now shortly after eight, and the car had arrived with the two men sent back the previous evening. Burnley gave them instructions about keeping a watch on Felix, then with Sergeant Hastings and Constable Walker he entered the car and was driven rapidly towards London.

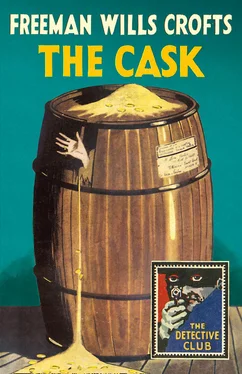

CHAPTER VII

THE CASK AT LAST

INSPECTOR BURNLEY reached Scotland Yard, after dropping Constable Walker at his station with remarks which made the heart of that observer glow with triumph and conjured up pictures of the day when he, Inspector Walker, would be one of the Yard’s most skilled and trusted officers. During the run citywards Burnley had thought out his plan of campaign, and he began operations by taking Sergeant Hastings to his office and getting down the large scale map.

‘Look here, Hastings,’ he said, when he had explained his theories and found what he wanted. ‘Here’s John Lyons and Sons’, the carriers where Watty is employed, and from where the dray was hired. You see it’s quite a small place. Here close by is Goole Street, and here is the Goole Street Post Office. Got the lie of those? Very well. I want you, when you’ve had your breakfast, to go out there and get on the track of Watty. Find out first his full name and address, and wire or phone it at once. Then shadow him. I expect he has the cask, either at his own house or hidden somewhere, and he’ll lead you to it if you’re there to follow. Probably he won’t be able to do anything till night, but of that we can’t be certain. Don’t interfere or let him see you if possible, but of course don’t let him open the cask if he has not already done so, and under no circumstances allow him to take anything out of it. I will follow you out and we can settle further details. The Goole Street Post Office will be our headquarters, and you can advise me there at, say, the even hours of your whereabouts. Make yourself up as you think best and get to work as quickly as you can.’

The sergeant saluted and withdrew.

‘That’s everything in the meantime, I think,’ said Burnley to himself, as with a yawn he went home to breakfast.

When some time later Inspector Burnley emerged from his house, a change had come over his appearance. He seemed to have dropped his individuality as an alert and efficient representative of Scotland Yard and taken on that of a small shopkeeper or contractor in a small way of business. He was dressed in a rather shabby suit of checks, with baggy knees and draggled coat. His tie was woefully behind the fashion, his hat required brushing, and his boots were soiled and down at heel. A slight stoop and a slouching walk added to his almost slovenly appearance.

He returned to the Yard and asked for messages. Already a telephone had come through from Sergeant Hastings: ‘Party’s name, Walter Palmer, 71 Fennell Street, Lower Beechwood Road.’ Having had a warrant made out for the ‘party’s’ arrest, he got a police motor with plain-clothes driver, and left for the scene of operations.

It was another glorious day. The sun shone out of a cloudless sky of clearest blue. The air had the delightful freshness of early spring. Even the Inspector, with his mind full of casks and corpses, could not remain insensible of its charm. With a half sigh he thought of that garden in the country which it was one of his dearest dreams some day to achieve. The daffodils would now be in fine show and the primroses would be on, and such a lot of fascinating work would be waiting to be done among the later plants …

The car drew up as he had arranged at the end of Goole Street and the Inspector proceeded on foot. After a short walk he reached his objective, an archway at the end of a block of buildings, above which was a faded signboard bearing the legend, ‘John Lyons and Son, Carriers.’ Passing under the arch and following a short lane, he emerged in a yard with an open-fronted shed along one side and a stable big enough for eight or nine horses on the other. Four or five carts of different kinds were ranged under the shed roof. In the middle of the open space, with a horse yoked in, was a dray with brown sides, and Burnley, walking close to it, saw that under the paint the faint outline of white letters could be traced. A youngish man stood by the stable door and watched Burnley curiously, but without speaking.

Читать дальше