COLLINS CRIME CLUB

an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Victor Gollancz 1947

Copyright © Rights Limited 1947

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018 / Cover image: © NRM/Pictorial Collection/Science and Society Picture Library - All rights reserved.

Edmund Crispin asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008228033

Ebook Edition © March 2018 ISBN: 9780008228040

Version: 2018-01-11

TO

GODFREY SAMPSON

My dear Godfrey,

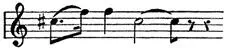

You’re not, I fancy, an habitual reader of such murderous tales as this, and in the ordinary way I should be decidedly shy of dedicating one of them to you. But a book with a background of Die Meistersinger – well, what else could I do? It was you who first introduced me to that noble work (in the days when the sum of my musical activity consisted in trying to evade piano lessons), and our mutual admiration of it is not the least of the many bonds of friendship between us. Accept the story, then, for the sake of its setting, and as a foretaste of the day when Wagner’s masterpiece returns to Covent Garden – without, let us hope, any of the dismal impediments which beset it in the following pages.

Yours as ever,

E. C.

Devon, 1946

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Footnotes

About the Author

Also in this Series

About the Publisher

There are few creatures more stupid than the average singer. It would appear that the fractional adjustment of larynx, glottis, and sinuses required in the production of beautiful sounds must almost invariably be accompanied – so perverse are the habits of Providence – by the witlessness of a barnyard fowl. Perhaps, though, the thing is not so much innate as a result of environment and training. This touchiness and irascibility, these scarifying intellectual lapses, are observable in actors as well – and it has long been noted that singers who are concerned with the theatre are more obtuse and trying than any other kind. One would be inclined, indeed, to attribute their deficiencies exclusively to the practice of personal display were it not for the existence of ballet-dancers, who (with a few notable exceptions) are most usually naïve and mild-eyed. Evidently there is no immediate and summary solution of the problem. The fact itself, however, is very generally admitted.

Certainly Elizabeth Harding was aware of it – perhaps only theoretically at first, but with a good deal of practical confirmation as the rehearsals of Der Rosenkavalier ran their course. She was therefore relieved to find that Adam Langley was considerably more cultured and intelligent, as well as more svelte and personable, than the majority of operatic tenors. It was her intention to marry him, and plainly the quality of his mind was a factor which had to be taken into account.

Elizabeth was not, of course, in any way a cold or calculating person. But most women – despite the romantic fictions which obscure the whole marriage problem – are realistic enough, before committing themselves, to examine with some care the merits and demerits of their prospective husbands. Moreover, Elizabeth had gained by her own talents a settled and independent position in life, and this was not, she had decided, to be abandoned improvidently at the behest of mere affection, however strong. She therefore reviewed the situation with characteristic thoroughness and clarity of mind.

And the situation was this, that she had fallen explicably and quite unexpectedly in love with an operatic tenor. In her more apprehensive moments, in fact, infatuation suggested itself to her as a more accurate term than love. The symptoms left her in no possible doubt as to her condition. They showed, even, so strong a resemblance to the tropes and platitudes of the conventional love-story as to be vaguely disconcerting. She thought about Adam before she went to sleep at night; she was still thinking about him when she woke up in the morning; she even – the ultimate degradation – dreamed about him; and she hurried to the opera-house to meet him with an eagerness quite inappropriate to a reserved and sophisticated young woman of twenty-six. In a way it was humiliating; on the other hand, it was decidedly the most delightful and exhilarating form of humiliation she had ever experienced – and that in spite of a sufficiency of practice in love and rather too much theoretical reading on the subject.

How it came about she was never able clearly to remember, but it seems to have happened quite suddenly, without gestation or warning. One day Adam Langley was an agreeable but undifferentiated member of an operatic company; the next he shone alone in planetary splendour, amid satellites grown spectral and unreal. Elizabeth felt, in the face of this phenomenon, something of the awe of a coenobite visited by an archangel, and was startled at the hurried refocusing of familiar objects which such an experience involves. ‘ Fallings from us, vanishings …’ She would certainly have resented this gratuitous upsetting of her normal outlook had it not been for the unprecedented sense of peace and happiness which it brought with it. ‘Darling Adam,’ she murmured that night to a hot and unresponsive pillow, ‘darling ugly Adam’ – a form of endearment which its object would probably have greatly resented had he known of it. There was more to the same effect, but such ecstasies make a poor showing by the time the printer has finished with them, and the reader will either have to take them for granted or imagine them for himself.

Читать дальше