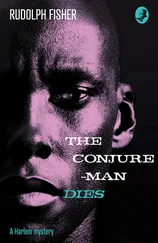

‘Yes—I’m Dr Archer.’

‘Well, arch on over here, will you, doc?’ urged the caller. ‘Sump’m done happened to Frimbo.’

‘Frimbo? The fortune teller?’

‘Step on it, will you, doc?’

Shortly, the physician, bag in hand, was hurrying up the greystone stoop behind his guide. They passed through the still open door into a hallway and mounted a flight of thickly carpeted stairs.

At the head of the staircase a tall, lank, angular figure awaited them. To this person the short, round, black, and by now quite breathless guide panted, ‘I got one, boy! This here’s the doc from ’cross the street. Come on, doc. Right in here.’

Dr Archer, in passing, had an impression of a young man as long and lean as himself, of a similarly light complexion except for a profusion of dark brown freckles, and of a curiously scowling countenance that glowered from either ill humour or apprehension. The doctor rounded the banister head and strode behind his pilot toward the front of the house along the upper hallway, midway of which, still following the excited short one, he turned and swung into a room that opened into the hall at that point. The tall fellow brought up the rear.

Within the room the physician stopped, looking about in surprise. The chamber was almost entirely in darkness. The walls appeared to be hung from ceiling to floor with black velvet drapes. Even the ceiling was covered, the heavy folds of cloth converging from the four corners to gather at a central point above, from which dropped a chain suspending the single strange source of light, a device which hung low over a chair behind a large desk-like table, yet left these things and indeed most of the room unlighted. This was because, instead of shedding its radiance downward and outward as would an ordinary shaded droplight, this mechanism focused a horizontal beam upon a second chair on the opposite side of the table. Clearly the person who used the chair beneath the odd spotlight could remain in relative darkness while the occupant of the other chair was brightly illuminated.

‘There he is—jes’ like Jinx found him.’

And now in the dark chair beneath the odd lamp the doctor made out a huddled, shadowy form. Quickly he stepped forward.

‘Is this the only light?’

‘Only one I’ve seen.’

Dr Archer procured a flashlight from his bag and swept its faint beam over the walls and ceiling. Finding no sign of another lighting fixture, he directed the instrument in his hand toward the figure in the chair and saw a bare black head inclined limply sidewise, a flaccid countenance with open mouth and fixed eyes staring from under drooping lids.

‘Can’t do much in here. Anybody up front?’

‘Yes, suh. Two ladies.’

‘Have to get him outside. Let’s see. I know. Downstairs. Down in Crouch’s. There’s a sofa. You men take hold and get him down there. This way.’

There was some hesitancy. ‘Mean us, doc?’

‘Of course. Hurry. He doesn’t look so hot now.’

‘I ain’t none too warm, myself,’ murmured the short one. But he and his friend obeyed, carrying out their task with a dispatch born of distaste. Down the stairs they followed Dr Archer, and into the undertaker’s dimly lighted front room.

‘Oh, Crouch!’ called the doctor. ‘Mr Crouch!’

‘That “mister” ought to get him.’

But there was no answer. ‘Guess he’s out. That’s right—put him on the sofa. Push that other switch by the door. Good.’

Dr Archer inspected the supine figure as he reached into his bag. ‘Not so good,’ he commented. Beneath his black satin robe the patient wore ordinary clothing—trousers, vest, shirt, collar and tie. Deftly the physician bared the chest; with one hand he palpated the heart area while with the other he adjusted the ear-pieces of his stethoscope. He bent over, placed the bell of his instrument on the motionless dark chest, and listened a long time. He removed the instrument, disconnected first one, then the other, rubber tube at their junction with the bell, blew vigorously through them in turn, replaced them, and repeated the operation of listening. At last he stood erect.

‘Not a twitch,’ he said.

‘Long gone, huh?’

‘Not so long. Still warm. But gone.’

The short young man looked at his scowling freckled companion.

‘What’d I tell you?’ he whispered. ‘Was I right or wasn’t I?’

The tall one did not answer but watched the doctor. The doctor put aside his stethoscope and inspected the patient’s head more closely, the parted lips and half-open eyes. He extended a hand and with his extremely long fingers gently palpated the scalp. ‘Hello,’ he said. He turned the far side of the head toward him and looked first at that side, then at his fingers.

‘Wh-what?’

‘Blood in his hair,’ announced the physician. He procured a gauze dressing from his bag, wiped his moist fingers, thoroughly sponged and reinspected the wound. Abruptly he turned to the two men, whom until now he had treated quite impersonally. Still imperturbably, but incisively, in the manner of lancing an abscess, he asked, ‘Who are you two gentlemen?’

‘Why—uh—this here’s Jinx Jenkins, doc. He’s my buddy, see? Him and me—’

‘And you—if I don’t presume?’

‘Me? I’m Bubber Brown—’

‘Well, how did this happen, Mr Brown?’

‘’Deed I don’ know, doc. What you mean—is somebody killed him?’

‘You don’t know?’ Dr Archer regarded the pair curiously a moment, then turned back to examine further. From an instrument case he took a probe and proceeded to explore the wound in the dead man’s scalp. ‘Well—what do you know about it, then?’ he asked, still probing. ‘Who found him?’

‘Jinx,’ answered the one who called himself Bubber. ‘We jes’ come here to get this Frimbo’s advice ’bout a little business project we thought up. Jinx went in to see him. I waited in the waitin’ room. Presently Jinx come bustin’ out pop-eyed and beckoned to me. I went back with him—and there was Frimbo, jes’ like you found him. We didn’t even know he was over the river.’

‘Did he fall against anything and strike his head?’

‘No, suh, doc.’ Jinx became articulate. ‘He didn’t do nothin’ the whole time I was in there. Nothin’ but talk. He tol’ me who I was and what I wanted befo’ I could open my mouth. Well, I said that I knowed that much already and that I come to find out sump’m I didn’t know. Then he went on talkin’, tellin’ me plenty. He knowed his stuff all right. But all of a sudden he stopped talkin’ and mumbled sump’m ’bout not bein’ able to see. Seem like he got scared, and he say, “Frimbo, why don’t you see?” Then he didn’t say no more. He sound’ so funny I got scared myself and jumped up and grabbed that light and turned it on him—and there he was.’

‘M-m.’

Dr Archer, pursuing his examination, now indulged in what appeared to be a characteristic habit: he began to talk as he worked, to talk rather absently and wordily on a matter which at first seemed inapropos.

‘I,’ said he, ‘am an exceedingly curious fellow.’ Deftly, delicately, with half-closed eyes, he was manipulating his probe. ‘Questions are forever popping into my head. For example, which of you two gentlemen, if either, stands responsible for the expenses of medical attention in this unfortunate instance?’

‘Mean who go’n’ pay you?’

‘That,’ smiled the doctor, ‘makes it rather a bald question.’

Bubber grinned understandingly.

‘Well here’s one with hair on it, doc,’ he said. ‘Who got the medical attention?’

‘M-m,’ murmured the doctor. ‘I was afraid of that. Not,’ he added, ‘that I am moved by mercenary motives. Oh, not at all. But if I am not to be paid in the usual way, in coin of the realm, then of course I must derive my compensation in some other form of satisfaction. Which, after all, is the end of all our getting and spending, is it not?’

Читать дальше