Collins Crime Club

an imprint of

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This eBook edition 2017

First published by Covici-Friede, New York 1932

‘John Archer’s Nose’ first published in The Metropolitan by Meeks Publishing Co. 1935 Introduction first published by Arno Press Inc. 1971

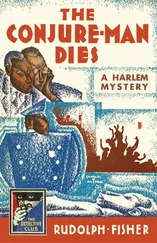

Cover design by Mike Topping © HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2020 Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008216450

Ebook Edition © January 2017 ISBN: 9780008216467

Version: 2020-09-28

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVI

Chapter XVII

Chapter XVIII

Chapter XIX

Chapter XX

Chapter XXI

Chapter XXII

Chapter XXIII

Chapter XXIV

John Archer’s Nose

Also by this Author

About the Author

About the Publisher

THE CONJURE-MAN DIES is, first and foremost, highly readable, wholly entertaining.

This should go without saying, since the book is a mystery novel of merit, and the sole function of any mystery story is to entertain. Of all types of fiction, it is probably the least pretentious, which is all in its favour at a time when the novel is so often used by authors as sugar coating for indigestible messes of philosophy or polemics calculated to make the reading of fiction a duty rather than a pleasure. Or for self-indulgent exercises in Beautiful Writing by poets manqués which make it neither a duty nor a pleasure.

This is not to deny that the formal mystery story does have its limitations, nor that too many of its practitioners, adopting these limitations as a rule book, tend to turn out a sort of mechanically contrived product, one cheapjack job after another rolling off the production line, each similar to the other beneath its coat of paint.

But it is a fact that a writer of authentic talent can and will create within the genre a novel which, while staying in bounds, offers a good example of that talent. Rudolph Fisher was such a writer, and the one mystery novel he wrote, The Conjure-Man Dies, originally published in 1932, offers striking evidence of it, especially when viewed in the light of its times. Its success on publication was great enough to carry it into production as a play by the Federal Theater Project in 1936. Its rediscovery, and appearance in this edition, are no more than proper tributes to both its readability and its merits as a record of its period.

Fisher himself was an extraordinary man. Born on 9 May 1897 in Washington, D.C., he graduated from Brown University with honours and went on to become a distinguished doctor of medicine, specializing in Roentgenology. At the height of his medical career, he turned to writing as an avocation and was soon being published by such magazines as Atlantic Monthly, Crisis, McClures, American Mercury and Story . A novel, The Walls of Jericho , published in 1928, received high critical praise, and when one adds the success of The Conjure-Man Dies to the list of Fisher’s literary achievements, it is plain that he was at least as talented in writing as he was in the practice of medicine. He died, however, on 26 December 1934, tragically young, and with a brilliantly promising career in letters unfulfilled.

His authorship of The Conjure-Man Dies gave Fisher a lonely distinction. Since the 1860s, when Metta Victor in America and Wilkie Collins in England produced the first formal mystery novels, there had been no Black writer who utilized this technique as a means of literary expression until Fisher came along. After his death there was again a hiatus until the 1960s, when Chester Himes appeared on the scene with his detective stories of Harlem. The time now ripe for it, Himes, an enormously talented writer himself, came to achieve a prestige and financial success from his mystery stories which Fisher could never have conceived.

What adds a special dimension to Fisher’s novel from the present reader’s point of view is the date of its publication, 1932. The African-American experience that year was still basically unchanged from the era of the Reconstruction. The vaunted Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s had not gone below the surface; excellent as some of the literature emerging from it was, there was a strong smell of the dilettante about the movement, largely emanating from the whites who were part of it. And the Great Depression had stopped even the meagre economic life-blood that was left in Black communities from flowing. If life everywhere was hard, life in Harlem came down to a desperate day-by-day struggle for mere survival in a world where the most minimal public works and inadequate welfare payments were only glimmerings on the Rooseveltian horizon, and where the word ‘militant’ was the exclusive property of white-dominated radical organizations.

Under these life-and-death conditions, the ‘Negro’ role, as prescribed by the white world of the 1930s, remained consistent. It was a familiar role, presented to the public by, among other things, the mystery stories of Octavus Roy Cohen in The Saturday Evening Post where the antics of the comically uppity Florian Slappey and his dull-witted, head-scratching cohorts illustrated it so vividly, and by mystery movies where the trusty but terrified and goggle-eyed Black servant could perform it larger than life on the screen.

On the other hand, Black Americans could take what comfort they might from white intellectual and dilettante who, heading in the opposite direction from the arrant racist, sentimentalized Black lives, romanticized their bitter struggle into something delightfully exciting, and, in effect, patted them on the head as one would a pet spaniel. It was ironic and inevitable that neither the racist nor the sentimentalist knew how nicely they were cooperating in the destruction of a people’s identity and individuality by barring the way to the honest exploration and discovery of them. This, of course, is the function of the stereotype, and it matters very little whether the stereotype is that of vicious hound or pet poodle.

The mystery novel of that day, where it dealt with Black people at all, played both angles. They were either servitors or hardboiled crap shooters, take it or leave it. Hardly surprising when one considers that, first, the mystery novel is popular fiction, and popular fiction always tends to cater to popular prejudices, and, second, that the genre itself had, by and large, used as its subjects the White Anglo-Saxon Protestant middle and upper classes, always acknowledging their superiority to the non-WASP world without question.

Читать дальше