‘Sad thoughts for a sweet evening,’ the old nurse said, brushing.

‘Why not? Unless (and I fear ’tis true) shades are coveted in summer, but with me ’tis fall of the leaf. Nay, I am young, surely, if sad thoughts please me. Yet, no; for there’s a taint of hope sweetens the biting of this sad sauce of mine; I can no more love it unalloyed, as right youth will do. Grow old is worse than but be old,’ she said, after a pause. ‘Growing-pains, I think.’

‘I love your hair in summer,’ the nurse said, lifting the shining tresses as it had been something too fair and too fine for common hand to touch. ‘The sun fetches out the gold in it, where in winter was left but red-hot fire-colours.’

‘Gold is good,’ said the Duchess. ‘And fire is good. But pluck out the silver.’

‘I ne’er found one yet,’ said she. ‘So the Lady Fiorinda shall have the Countess’s place in the bedchamber? I had thought your grace could never abide her?’

The Duchess smiled, reaching for her hand-glass of emerald and gold. ‘Today, just upon the placing of the breakfasting-covers, I took a resolve to choose my women as I choose gowns. And black most takingly becomes me. Myrrha, what scent have you brought me?’

‘The rose-flower of Armash.’

‘It is too ordinary. Tonight I will have something more strange, something unseasonable; something springlike to confound midsummer. Wood-lilies: that were good: in the golden perfume-sprinkler. But no,’ she said, as Myrrha arose to go for these: ‘they are earthy. Something heaven-like for tonight. Bring me wood gentians: those that grow many along one stem, so as you would swear it had first been Solomon’s seal but, with leaving to hang its pale bells earthward, and with looking skywards instead through a roof of mountain pines, had turned blue at last: colour of the heaven it looked to.’

‘Madam, they have no scent.’

‘How can you know? What is not possible, tonight? Find me some. But see: no need,’ she said. ‘Fiorinda! This is take to your duties as an eagle’s child to the wind.’

‘I am long used to waiting on myself,’ said that lady, coming down the steps out of an archway of leafy darknesses, stone pine upon the left and thick-woven traceries of an old gnarled strawberry-tree on the right, her arms full of blue wood gentians, and with two little boys in green coats, one bearing upon a tray hippocras in a flagon and golden globlets, and the other apricots and nectarines on dishes of silver.

‘Have they scent indeed?’ said the Duchess, taking the gentians.

‘Please your grace to smell them.’

The Duchess gathered them to her face. ‘This is magic.’

‘No. It is the night,’ said Fiorinda, bidding the boys set down and begone. The shadow of a smile passed across her lips in the meeting of green eye-glances, hers and the Duchess’s, over the barrier of sky-blue flowers. ‘Your grace ought to kiss them.’

The Duchess did so. Again their glances met. The scent of those woodland flowers, subtle and elusive, spoke a private word as into the inward and secretest ear of her who inhaled that perfume: as to say, privately, ‘I have ended the war. Five months sooner than I said, my foot is on their necks. And so, five months before the time appointed – I will have you, Amalie.’ She caught her breath; and that perfume lying so delicate on the air that no sense but hers might savour it, said privately again to Amalie’s blood, ‘And that was in that room in the tower, high upon Acrozayana, with great windows that take the sunset, facing west over Ambremerine, but the bedchamber looks east over the sea: the rooms where today Barganax your son has his private lodging. And that was this very night, of midsummer’s day, three-and-twenty years ago.’ She dismissed her girls, Myrrha and Violante, with a sign of the hand, and, while the nurse braided, coiled and put up her hair, kissed the flowers again, smoothed her cheek against them as a beautiful cat will do, gathered them to her throat. ‘Dear Gods!’ she said, ‘were it not blasphemy, I could suppose myself the Queen of Heaven in Her incense-sweet temple in Cyprus, as in the holy hymn, choosing out there My ornaments of gold and sweet-smelling soft raiment, and so upon the wind to Ida, to that princely herdsman,

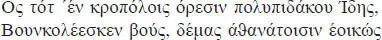

Who, on the high-running rangesof many-fountain’d Ida,

Neat-herd was of neat, but a God in frame and seeming.’

‘Blasphemy?’ said Fiorinda. ‘Will you say the Gods were e’er angered at blasphemy? I had thought it was but false gods that could take hurt from that.’

‘Even say they be not angered, I would yet fear the sin in it,’ said the Duchess: ‘the old son of – man to make himself equal with God.’

Fiorinda said, ‘I question whether there be in truth any such matter as sin.’

The Duchess, looking up at her, abode an instant as if bedazzled and put out of her reckonings by some character, alien and cruel and unregarding; that seemed to settle with the dusk on the cold features of that lady’s face. ‘Give me my cloak,’ she said then to the nurse, and standing up and putting it about her, ‘go before and see all fit in my robing-room. Then return with lights. We’ll come thither shortly.’ Then, the nurse being gone, ‘I will tell you an example,’ she said. ‘It is a crying and hellish sin, as I conceive it, to have one’s husband butchered with bodkins on the piazza steps in Krestenaya.’

Fiorinda raised her eyebrow in a most innocent undisturbed surprise. ‘That? I scarce think Gods would fret much at that. Besides, it was not my doing. Though, truly,’ she said, very equably, and upon a lazy self-preening cadence of her voice, ‘’twas no more than the quit-claim due to him for unhandsome usage of me.’

‘It was done about the turn of the year,’ said the Duchess; ‘and but now, in May, we see letters patent conferring upon your husband the lieutenancy of Reisma: the Lord Morville, your present, second, husband, I mean. What qualification fitted Morville for that office?’

‘I’ll not disappoint your grace of your answer. His qualification was, being husband of mine; albeit then but of three weeks’ standing.’

‘You are wisely bent, I find. Tell me: is he a good husband of his own honour?’

‘Truly,’ answered she, ‘I have not given much thought to that. But, now I think on’t, I judge him to be one of those bull-calves that have it by nature to sprout horns within the first year.’

‘A notable impudency in you to say so. But it is rifely reported you were early schooled in these matters.’

Fiorinda shrugged her shoulders. ‘The common people,’ she said, ‘were ever eager to credit the worst.’

‘Common? Is that aimed at me?’

‘O no. I never heard but that your grace’s father was a gentleman by birth.’

‘How old are you?’ said the Duchess.

‘Nineteen. It is my birthday.’

‘Strange: and mine. Nineteen: so young, and yet so very—’

‘Your grace will scarcely set down my youth against me as a vice, I hope: youth, and no stomach for fools—’

‘O I concern not myself with your ladyship’s vices. Enough with your virtues: murder, and (shall we say?) poudre agrippine .’

Fiorinda smoothed her white dress. ‘The greater wonder,’ she said, with a delicate air, ‘that your grace should go out of your way to assign me a place at court, then.’

‘You think it a wonder?’ the Duchess said. ‘It is needful, then, that you understand the matter. It is not in me to grudge a friend’s pleasures. Rather do I study to retain a dozen or so women of your leaven about me, both as foils to my own qualities and in case ever, in an idle hour, he should have a mind for such highly seasoned sweetmeats.’

Читать дальше