Pollard traded one and a half barrels of beans for thirty hogs, whose squeals and grunts and filth turned the deck of the Essex into a barnyard. The impressionable Nickerson was disturbed by the condition of these animals. He called them “almost skeletons,” and noted that their bones threatened to pierce through their skin as they walked about the ship.

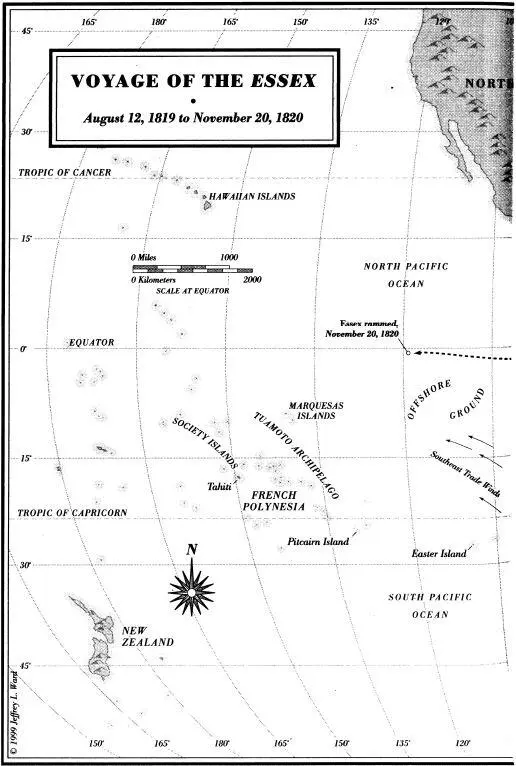

NOT until the Essex had crossed the equator and reached thirty degrees south latitude—approximately halfway between Rio de Janeiro and Buenos Aires—did the lookout sight the first whale of the voyage. It required sharp eyes to spot a whale’s spout: a faint puff of white on the distant horizon lasting only a few seconds. But that was all it took for the lookout to bellow, “There she blows!” or just “B-l-o-o-o-w-s!”

After more than three whaleless months at sea, the officer on deck shouted back in excitement, “Where away?” The lookout’s subsequent commentary not only directed the helmsman toward the whales but also worked the crew into an ever increasing frenzy. If he saw a whale leap into the air, the lookout cried, “There she breaches!” If he caught a glimpse of the whale’s horizontal tail, he shouted, “There goes flukes!” Any indication of spray or foam elicited the cry “There’s white water!” If he saw another spout, it was back to “B-l-o-o-o-w-s!”

Under the direction of the captain and the mates, the men began to prepare the whaleboats. Tubs of harpoon line were placed into them; the sheaths were taken off the heads of the harpoons, or irons, which were hastily sharpened one last time. “All was life and bustle,” remembered one former whaleman. Pollard’s was the single boat kept on the starboard side. Chase’s was on the aft larboard, or port, quarter. Joy’s was just forward of Chase’s and known as the waist boat.

Once within a mile of the shoal of whales, the ship was brought to a near standstill by backing the mainsail. The mate climbed into the stern of his whaleboat and the boatsteerer took his position in the bow as the four oarsmen remained on deck and lowered the boat into the water with a pair of block-and-tackle systems known as the falls. Once the boat was floating in the water beside the ship, the oarsmen—either sliding down the falls or climbing down the side of the ship—joined the mate and boatsteerer. An experienced crew could launch a rigged whaleboat from the davits in under a minute. Once all three whaleboats were away, it was up to the three shipkeepers to tend to the Essex.

At this early stage in the attack, the mate or captain stood at the steering oar in the stern of the whaleboat while the boatsteerer manned the forward-most, or harpooner’s oar. Aft of the boatsteerer was the bow oarsman, usually the most experienced foremast hand in the boat. Once the whale had been harpooned, it would be his job to lead the crew in pulling in the whale line. Next was the midships oarsman, who worked the longest and heaviest of the lateral oars—up to eighteen feet long and forty-five pounds. Next was the tub oarsman. He managed the two tubs of whale line. It was his job to wet the line with a small bucketlike container, called a piggin, once the whale was harpooned. This wetting prevented the line from burning from the friction as it ran out around the loggerhead, an upright post mounted on the stern of the boat. Aft of the tub oarsman was the after oarsman. He was usually the lightest of the crew, and it was his job to make sure the whale line didn’t tangle as it was hauled back into the boat.

Three of the oars were mounted on the starboard side of the boat and two were on the port side. If the mate shouted, “Pull three,” only those men whose oars were on the starboard side began to row. “Pull two” directed the tub oarsman and bow oarsman, whose oars were on the port side, to row. “Avast” meant to stop rowing, while “stern all” told them to begin rowing backward until sternway had been established. “Give way all” was the order with which the chase began, telling the men to start pulling together, the after oarsman setting the stroke that the other four followed. With all five men pulling at the oars and the mate or captain urging them on, the whaleboat flew like a slender missile over the wave tops.

The competition among the boat-crews on a whaleship was always spirited. To be the fastest gave the six men bragging rights over the rest of the ship’s crew. The pecking order of the Essex was about to be decided.

With nearly a mile between the ship and the whales, the three crews had plenty of space to test their speed. “This trial more than any other during our voyage,” Nickerson remembered, “was the subject of much debate and excitement among our crews; for neither was willing to yield the palm to the other.”

As the unsuspecting whales moved along at between three and four knots, the three whaleboats bore down on them at five or six knots. Even though all shared in the success of any single boat, no one wanted to be passed by the others; boat-crews were known to foul one another deliberately as they raced side by side behind the giant flukes of a sperm whale.

Sperm whales are typically underwater for ten to twenty minutes, although dives of up to ninety minutes have been reported. The whaleman’s rule of thumb was that, before diving, a whale blew once for each minute it would spend underwater. Whalemen also knew that while underwater the whale continued at the same speed and in the same direction as it had been traveling before the dive. Thus, an experienced whaleman could calculate with remarkable precision where a submerged whale was likely to reappear.

Nickerson was the after oarsman on Chase’s boat, placing him just forward of the first mate at the steering oar. Chase was the only man in the boat who could actually see the whale up ahead. While each mate or captain had his own style, they all coaxed and cajoled their crews with words that evoked the savagery, excitement, and the almost erotic bloodlust associated with pursuing one of the largest mammals on the planet. Adding to the tension was the need to remain as quiet as possible so as not to alarm or “gally” the whale. William Comstock recorded the whispered words of a Nantucket mate:

Do for heaven’s sake spring. The boat don’t move. You’re all asleep; see, see! There she lies; skote, skote! I love you, my dear fellows, yes, yes, I do; I’ll do anything for you, I’ll give you my heart’s blood to drink; only take me up to this whale only this time, for this once, pull. Oh, St. Peter, St. Jerome, St. Stephen, St. James, St. John, the devil on two sticks; carry me up; O, let me tickle him, let me feel of his ribs. There, there, go on; O, O, O, most on, most on. Stand up, Starbuck [the harpooner]. Don’t hold your iron that way; put one hand over the end of the pole. Now, now, look out. Dart, dart.

As it turned out, Chase’s crew proved the fastest that day, and soon they were within harpooning distance of the whale. Now the attention turned to the boatsteerer, who had just spent more than a mile rowing as hard as he possibly could. His hands were sore, and the muscles in his arms were trembling with exhaustion. All the while he had been forced to keep his back turned to a creature that was now within a few feet, or possibly inches, of him, its tail—more than twelve feet across—working up and down within easy reach of his head. He could hear it—the hollow wet roar of the whale’s lungs pumping air in and out of its sixty-ton body.

But for Chase’s novice harpooner, the twenty-year-old Benjamin Lawrence, the mate himself was as frightening as any whale. Having been a boatsteerer on the Essex ’s previous voyage, Chase had definite ideas on how a whale should be harpooned and maintained a continual patter of barely audible, expletive-laced advice. Lawrence tucked the end of his oar handle under the boat’s gunnel, then braced his leg against the thigh thwart and took up the harpoon. There it was, the whale’s black body, glistening in the sun. The blowhole was on the front left side of the head, and the spout enveloped Lawrence in a foulsmelling mist that stung his skin.

Читать дальше