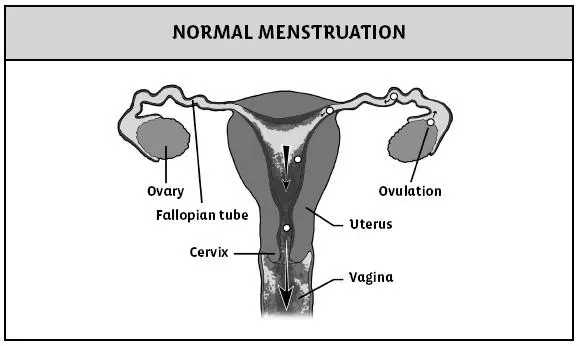

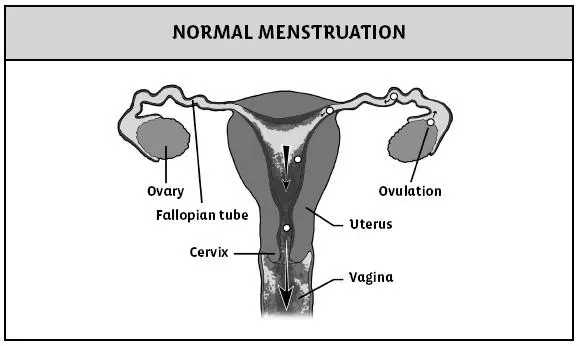

When I tell women that they may have endometriosis, the women usually have a laundry list of questions. This is good. I find too many doctors who are not gynecologists know very little about endometriosis, and most gastroenterologists don’t even suspect it as a possible cause of symptoms. They often settle on a diagnosis before their patient has been properly heard. In order to understand what endometriosis is, it’s helpful to review the anatomy of the gynecological tract and normal menstruation. (See Figure 2-1).

Figure 2-1. Menstruation is monthly bleeding from the uterus. The menstrual cycle is considered to start with the first day of bleeding. The next cycle begins at the time of first bleeding with the subsequent period. During the first half of the cycle (follicular phase) an egg in the ovary matures and the wall of the uterus thickens. At about day fourteen the egg is released from the ovary (ovulation) and travels through the fallopian tube to the uterus. The uterus lining continues to thicken (luteal phase). Then, if no fertilization of the egg with sperm takes place, the lining of the uterus is shed and discharged through the cervix and vagina as your period. Oral contraceptive pills will interrupt the menstrual cycle, but when menstruation occurs, it is normal.

Here are some common questions I hear from my patients:

Several of my friends have endometriosis, and one of them is having trouble getting pregnant. What is it?

Endometriosis occurs when the cells that line the wall of the uterus—which a woman should pass with each menstrual period—end up growing outside the uterus instead. During normal menstruation the uterine lining cells exit through the vagina (see Figure 2-1). But almost every woman also has retrograde menstruation in which some of the uterine-lining cells travel out the fallopian tubes and into the pelvic cavity, thereby tracing the egg’s path in reverse from ovary to uterus (see Figure 2-2). This is called retrograde menstruation. When a person develops endometriosis these cells take up residence in the wrong places—sometimes even growing in and sticking to the bowel and other nearby organs—and can bleed with each period, causing pain and scarring. When this happens, a woman might get cyclical or constant abdominal pain. Usually, the endometriosis exists in the lower region of the pelvis, but it can creep onto other organs, too. (See Figure 2-3). Bowel endometriosis affects about one-third of women with endometriosis and can cause severe pain with bowel movements.

Figure 2-2. The menstrual cycle is the same as in normal menstruation. However, when the lining of the uterus is shed, it does not travel exclusively through the cervix and vagina. Some of the cells from the uterine lining travel upward, through the fallopian tubes and then out into the pelvis. This sets up the possibility for endometriosis to occur.

Figure 2-3. Endometriosis occurs when the cells of the lining of the uterus take up residence outside of the uterus. The endometriosis lesions can be different sizes and vary from clear to red to black. This drawing shows the common areas where endometriosis occurs and the close proximity of the bowel to the uterus, which explains how endometriosis might end up on the bowel. The sigmoid colon is behind the uterus (toward the spine) and the rectum is behind the vagina. The rectouterine fold, also known as the uterosacral ligament, connecting the uterus and the sacrum, part of the spinal column, is a common place for endometriosis. The broad ligament connects the uterus to the wall of the pelvis and is in a perfect location for implantation of the endometriosis.

Is endometriosis common?

Approximately 5 percent of all menstruating women and girls suffer from endometriosis. However, for women who are infertile and can’t get pregnant naturally, endometriosis can be the case 25 to 40 percent of the time! For teenage girls with very painful periods, endometriosis is the cause nearly 50 percent of the time.

If almost every woman has period cells that pass from the fallopian tubes, why don’t all of us who still menstruate have endometriosis?

Women who do get endometriosis have several things going on: First of all, the cells have to stick to a place where they can grow and attract more cells. These cells then have to form blood vessels within the clump or implant—not an easy feat! Genetics and environmental factors also play a part. How your body reacts to these misplaced cells strongly contributes to the damage the endometriosis may cause.

Interestingly, tall, thin women are more likely to have endometriosis than short, heavy women. Ahem! This does not mean you should gain weight to decrease your risk for endometriosis. Obesity, of course, has many negative effects on your health. Some studies have shown that caffeine and alcohol intake also increase the risk of endometriosis, while smoking and exercise reduce the risk. (Of course, I’m not going to endorse smoking, either.)

I feel bloated and crampy all the time. My doctor says it’s IBS. My coworker has endometriosis and told me I probably do, too, based on my symptoms. I’m starting to freak out. How do I know that I don’t?

Endometriosis can be tough to diagnose because several of the symptoms—like diarrhea and cramping—can mimic irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Don’t settle for an IBS diagnosis, especially if you’re having trouble conceiving. Here are some symptoms of endometriosis:

The Big Ds

Dysmenorrhea—Otherwise known as debilitating menstrual cramps.

Dyspareunia—Painful sex.

Dyschezia—Painful bowel movements.

Dysuria—Painful or uncomfortable peeing.

PLUS:

Recurrent miscarriage—Particularly pregnancies that end within two to three months.

Nausea, vomiting and/or diarrhea—Particularly during PMS.

Unusually long or short menstrual periods—a normal period should last between three and five days.

What is the best way to diagnose endometriosis?

The best way to make the diagnosis is by a surgical procedure called a laparoscopy. In this procedure, a small cut is made under the belly button, infused carbon dioxide distends the belly and a scope is inserted. The gynecologist or surgeon looks around to identify any raised blue, red or clear areas that could be endometriosis and examines the ovaries for cysts. Often these areas can be treated, and scar tissue can be cut (released).

Surgery is not always needed for the diagnosis. Other tests can be done but might not be as good for detecting very small lesions or for identifying scar tissue. These tests include an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan of the pelvis, which can identify pelvic endometriosis; a CT (computerized tomography) scan with air or contrast in the rectum; and an air-contrast barium enema (to detect endometriosis on the bowel). An endoscopic ultrasound, in which an ultrasound device on the end of a scope is inserted into the rectum, can take images of the surrounding area and often see if there is endometriosis in the bowel wall. Traditional ultrasounds, with the ultrasound probe placed on the abdominal wall or in the vagina, and colonoscopies aren’t particularly helpful for the diagnosis of endometriosis.

If endometriosis is so common, why is it so hard to pinpoint and diagnose?

The symptoms of endometriosis tend to mimic other issues. Women usually have different symptoms and may seek attention from a primary care physician, gastroenterologist or gynecologist. Abdominal or pelvic pain is a very common complaint. However, change in the bowels may also be a complaint. Endometriosis is not often the first thought for the internist or gastroenterologist.

Читать дальше