He took and passed an accountancy course and began to dabble in journalism, something he had already practised at school, where he ran the class journal. And he got married. Marie Antoinette, an appropriate name for the wife of a future African monarch, was only fourteen at the time, but in traditional Congolese society this was not considered precocious. Still smarting from his schoolroom clashes with the priests, Mobutu chose not to wed in church. His contribution to the festivities – a crate of beer – betrayed the modesty of his income at the time.

Photos taken during those years show a gawky Mobutu, all legs, ears and glasses, wearing the colonial shorts more reminiscent of a scout outfit than a serious army uniform. Marie Antoinette, looking the teenager she still was, smiles shyly by his side. Utterly loyal, she was nonetheless a feisty woman, who never let her husband’s growing importance cow her into silence. ‘You’d be talking to him and she would come in and chew him up one side and down the other,’ said Devlin. ‘She was not impressed by His Eminence, and he would immediately switch into Ngbandi with her because he knew I could understand Lingala or French.’

A Belgian colonial had started up a new Congolese magazine, Actualités Africaines , and was looking for contributors. Because Mobutu, as a member of the armed forces, was not allowed to express political opinions, he wrote his pieces on contemporary politics under a pseudonym. Given the choice between extending his army contract and getting more seriously involved in journalism, he chose the latter. Although initial duties involved talent-spotting Congolese beauties to fill space for an editor nervous of polemics, Mobutu was soon writing about more topical events, scouring town on his motor scooter to collect information. The world was opening up. A 1958 visit to Brussels to cover the Universal Exhibition was a revelation and he arranged a longer stay for journalistic training. By that time he had got to know the young Congolese intellectuals who were challenging Belgium’s complacent vision of the future, staging demonstrations, making speeches and being thrown into jail.

One man in particular, Lumumba, became a personal friend. The two men shared many of the same instincts: a belief in a united, strong Congo and resentment of foreign interference. Thanks to his influence Mobutu, who had always protested his political neutrality, was to become a card-carrying member of the National Congolese Movement, the party Lumumba hoped would rise above ethnic loyalties to become a truly national movement.

But even in those early days there are question marks over Mobutu’s motives. Congolese youths studying in Brussels were systematically approached by the Belgian secret services with an eye to future cooperation. Several contemporaries say that by the time Mobutu had made his next career step – moving from journalism to act as Lumumba’s trusted personal aide, deciding who he saw, scheduling his activities, sitting in for him at economic negotiations in Brussels – he was an informer for Belgian intelligence.

What were the qualities that made so many players in the Congolese game single him out? Some remarked on his quiet good sense, the pragmatism that helped him rein in the excitable Lumumba when he was carried away by his own rhetoric. It accompanied an appetite for hard work: Mobutu was regularly getting up at 5 in the morning and working till 10 p.m. during the crisis years. But the characteristic that, more than any other, eventually decreed that he won control of the country’s army was probably the brute courage he attributed to that childhood brush with the leopard.

Bringing the 1960 mutiny to heel involved standing up in front of hundreds of furious, drunk soldiers who had plundered the barracks’ weapons stores and quelling them through sheer force of personality. And Mobutu carried out that task, one that civilian politicians understandably balked at, not once but many times. ‘I’ve been in enough wars to know when men are putting it on and when they really are courageous,’ said Devlin. ‘And Mobutu really was courageous.’ Once, he watched Mobutu curb a mutiny by the police force. ‘They were hollering and screaming and pointing guns at him and telling him not to come any closer or they’d shoot. He just started talking quietly and calmly until they quietened down, then he walked along taking their guns from them, one by one. Believe me, it was hellish impressive.’

The quality was to be tested repeatedly. The assassination attempt foiled by Devlin’s intervention was one of five such bids in the week that followed Mobutu’s ‘peaceful revolution’. Such was the danger that Mobutu sent his family to Belgium. Marie-Antoinette deposited her offspring and returned in twenty-four hours, refusing to leave her husband’s side. ‘If they kill him they have to kill me,’ she told friends.

What constitutes charm? A presence, a capacity to command attention, an innate conviction of one’s own uniqueness, combined, as often as not, with the more manipulative ability of making the interlocutor believe he has one’s undivided attention and has gained a certain indefinable something from the encounter. Whatever its components, the quality was innate with Mobutu, but definitely blossomed as growing power swelled his sense of self-worth. In the early 1960s European observers referred to him as the ‘doux colonel’ (mild-mannered colonel), suggesting a certain diffidence. Nonetheless he was a remarkable enough figure to prompt Francis Monheim, a Belgian journalist covering events, to feel he merited an early hagiography. By the end of his life, whether they loathed or loved him, those who had brushed against Mobutu rarely forgot the experience. All remarked on an extraordinary personal charisma.

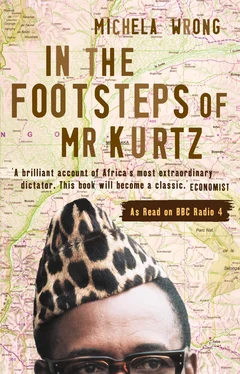

‘I’ve never seen a photograph of Mobutu that did him justice, that makes him look at all impressive,’ claimed Kim Jaycox, the World Bank’s former vice-president for Africa, who met Mobutu many times. ‘It’s like taking a photograph of a jacaranda tree, you can’t capture the actual impact of that colour, of that tree. In photos he looked kind of unintelligent and without lustre. But when you were in his presence discussing anything that was important to him, you suddenly saw this quite extraordinary personality, a kind of glowing personality. No matter what you thought of his behaviour or what he was doing to the country, you could see why he was in charge.’

He had a gift for the grand gesture, a stylish bravado that captured the imagination. Setting off for Shaba to cover the invasions of the 1970s, foreign journalists would occasionally disembark to discover, to their astonishment, that their military plane had been flown by a camouflage-clad president, showing off his pilot’s licence.

There were some of the personal quirks that can count for much when it comes to political networking and pressing the flesh, whether in a democracy or a one-party state. He had a superb memory and on the basis of the briefest of meetings would be able, re-encountering his interlocutor many years later, to recall name, profession and tribal affiliation. ‘It was phenomenal,’ remembers Honoré Ngbanda, who as presidential aide for many years was responsible for briefing Mobutu for his meetings. ‘Whether it was a visual memory or a memory for dates, he could remember things that had happened 10 years ago: the date, the day and time. His memory was elephantine.’

Mobutu had another of the characteristics of the manipulative charmer: he could be all things to all men, holding up a mirror to his interlocutors that reflected back their wishes, convincing each that he perfectly understood their predicament and was on their side. ‘He could treat people with kid gloves or he could treat them with a steel fist,’ remembered a former prime minister who saw more of the fist than the glove. ‘It was different for everyone. He was very clever at tailoring the response to the individual.’

Читать дальше