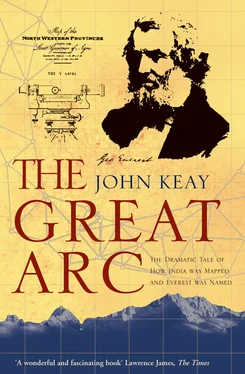

Colonel Lambton was the originator and now Superintendent of the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India. For seventeen years he had been spinning a web of giant geometry across the Indian peninsula without ever having had to thrash any of its teeming peoples. Tactful, patient and indestructible, Lambton seemed immune to India’s frustrations, the result of a long wilderness experience in North America and of an attachment to science so obsessive and disinterested that even his critics were inclined to indulge him. Colonel Lambton beguiled India; but Lieutenant George Everest, his eager new assistant, chastised it.

The name, incidentally, was pronounced not ‘Ever-rest’ (like ‘cleverest’), but ‘Eve-rest’ (like ‘cleave-rest’). That was how the family always pronounced it, and the Lieutenant would not have thanked you for getting it wrong. Years later a fellow officer would make the mistake of calling him a ‘Kumpass Wala’. No offence was meant. ‘Kumpass Wala’, or ‘compass-wallah’, was an accepted Anglo-Indian term for a surveyor. Everest, however, accepted nothing of the sort. He detested what he called ‘nicknames’ and, though it was not perhaps worth a dawn challenge, he demanded – and received – abject apologies. Getting on the wrong side of George Everest was an occupational hazard with which even British India would only slowly come to terms.

With the mutiny quelled and the mutineers ‘finding that, when they knew me better, good behaviour was a perfect security against all unkindness’, a self-righteous Everest pressed on for the jungles beside the Kistna. It was July, the month when the monsoon breaks. On time, the heavens duly opened just as he climbed a hill to his first observation post.

Survey work was conducted during and immediately after the monsoon because, regardless of the discomfort, it was only then that the dust was laid and the heat-haze dispersed. In the interludes of bright sunshine, the atmosphere was at its clearest; in fact it became so transparent that Everest fancied he could see forever and that ‘the proximity of objects was only to be judged by their apparent magnitudes’. Trigonometrical surveying depended on the sighting of slender signal posts over distances of more than twenty miles. The monsoon’s perfect visibility was therefore ideal. Spying a long dark ridge all of sixty miles to the east, Everest despatched his four best signalmen to occupy its heights. The ridge, he understood, was called Panch Pandol, and the signalmen were to erect their flagpole there in readiness for his observations. Meanwhile he continued south to the Kistna with the rest of his party.

Although visibility was greatly enhanced by the monsoon, mobility was not. Dry riverbeds instantly became raging torrents full of uprooted trees. The Musi, a tributary of the Kistna, rose so rapidly that Everest found himself cut off from his supplies. On iron rations therefore, and denied the normal crossing on the Kistna, which was on the other side of its confluence with the Musi, he headed downstream to where an alternative ferry was said to operate at a spot about fifty miles above the modern city of Vijayawada.

The Kistna, one of India’s mightiest rivers, was now thrashing dementedly over steeply shelving rock like a panic-stricken patient beneath the surgeon’s knife. Crossing it meant trusting oneself to a coracle, a small circular vessel, more bowl than boat, made of woven rattans and faced with hide. Everest likened it to a leather basket. Such craft, still used in many parts of India, are highly portable and sometimes formed part of a surveyor’s outfit. Although not so provided, Everest found one abandoned by the river.

While it was undergoing the necessary repairs at the hands of the village cobbler, Everest ordered his ‘carriage-cattle’ to be swum across the flood. Fortunately they were not actually cattle, ox-carts being useless in roadless jungle, but a species he deemed ‘more at home in the water than any other quadruped’, namely elephants. As he also noted, elephants are extraordinarily sagacious. The Survey’s beasts duly swayed to the bank, took a long look at the rocks and the raging waters, assessed the mix of caresses and curses on offer, and opted to stay dry. ‘Probably it was fortunate,’ Everest adds, ‘for these powerful animals … are, from the size of their limbs, in need of what sailors term sea-room, and in a river like the Kistna … were very liable to receive some serious injury.’

This reverse meant a change of plan. Dr Henry Voysey, one of Everest’s two British companions and the Survey’s geologist-cum-physician, was left on the north bank with the main party plus elephants, horses, tents and baggage. Meanwhile Everest and a dozen men, balancing the Survey’s cumbersome theodolite between them, crossed to the other side. Three trips had to be made; and since the coracle had to undergo repairs after each, it took most of the day. Then, deceived by the visibility into thinking it was only a couple of miles away, Everest immediately set out for his next observation post.

The couple of miles turned out to be twelve. They included both jungle work and rock-climbing. By the time the hill of Sarangapalle was reached it was dusk, and big black clouds, aflicker with lightning, were piling up overhead. ‘At last,’ noted Everest, ‘when all their batteries were in order, a tremendous crash of thunder burst forth, and, as if all heaven were converted into one vast shower-bath, the vertical rain poured down in large round drops upon the devoted spot of Sarangapullee.’

Tentless in the deluge, Everest and his men bent branches to make bivouacs. His own was improved by a bedstead and an umbrella, between which he slept the sleep of the utterly exhausted, oblivious alike of his squelching tweeds, puddled bedding and benighted followers. ‘These evils might have been borne without any ill effects,’ he insists, ‘but for other circumstances of more serious consequence.’

The natives of India, according to Everest, ‘with their minds bowed down under the incubus of superstition’, attributed all fevers to witchcraft, and ignored natural causes. He, on the other hand, while amused by the idleness and absurdity of these doctrines, knew better. Malaria and ‘typhus’ fevers were alike the result of ‘a poisonous influence in the air’ which emanated from moist and ‘unwholesome’ soils. Under the impression that he was contributing to medical research, he examined the different schists and shales, the crystalline sandstone of Sarangapalle, the blue limestones of the Kistna and the porous sandstone of the Godavari in minute detail. These, he believed, were the ‘other circumstances’ which would prove of such serious consequence for his survey.

At the time most of his contemporaries shared these medical views. But, in a nice case of geographical coincidence, Hyderabad would host a further attempt to discover the natural causes of malaria. Seventy years later in a house in Begampet, now a suburb of Hyderabad city, Surgeon Ronald Ross would experiment on the insects of the Kistna-Godavari jungles and trace the malaria parasite to the anopheles mosquito. Everest’s ideas of ‘malarial vapours’ would thereby be exposed as every bit as idle and absurd as those of his followers.

After observing from Sarangapalle, he recrossed the Kistna and rejoined his camp to head north towards the Godavari. On the way he conducted observations to prominent hills like that to which he had earlier sent his signalmen. The survey on which he was engaged was what was known as a ‘secondary triangulation’. It was intended to cover all the country between the Kistna and the Godavari with a network of imaginary triangles whose sides connected intervisible observation posts.

Triangulation means simply ‘triangle-ing’, or conceiving three mutually visible reference points, usually on prominent hills or buildings, as the corners of a triangle. Knowing the exact distance between two of these points, and then measuring at each the angles made by their connecting sight-line with those to the third point, the distance and position of the third point can be established by trigonometry. One of the newly determined sides of this triangle then becomes the base for a second triangle embracing a new reference point whose position is determined in the same way. Another triangle is thus completed and one of its sides becomes the base for a third, And so on. A web, or chain, of triangles results; and Everest’s job was to extend this web of triangulation over the whole Kistna-Godavari region.

Читать дальше