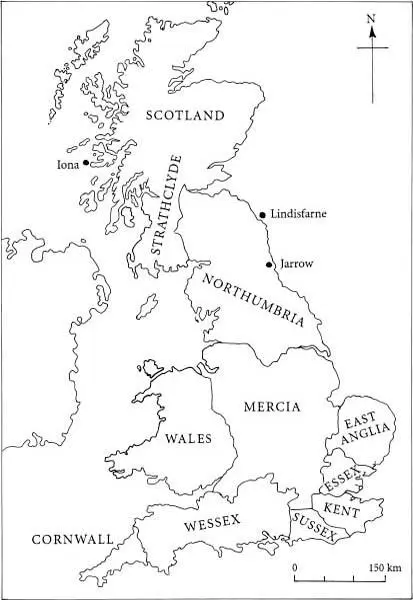

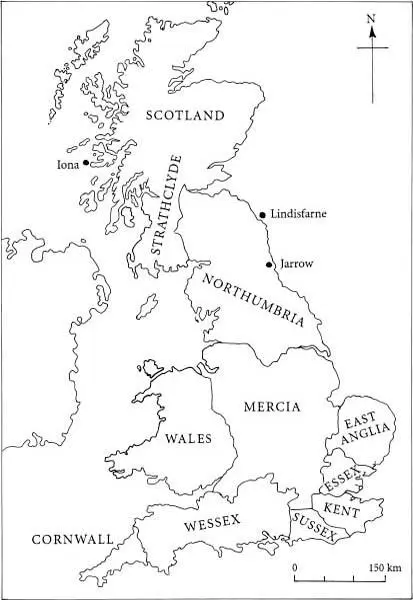

FIG 8 The principal kingdoms of Britain in the late eighth century (Middle Saxon period) .

Contrary to popular belief, Offa’s Dyke does not extend from sea to sea across the entire eastern approaches to Wales. In fact the original Mercian earthwork is only found across the central part of Wales – a stretch of just over a hundred kilometres. The rest is unprotected, and David Hill believes that this stretch represents the boundary between Mercia and Powys, the source of the principal recurrent threat. Mercia was not at war with the kingdoms of Gwynedd to the north, or with Ercing or Gwent to the south. So that was the boundary Offa defended – there was no point in doing any more. This tells us that boundaries and political treaties were generally honoured. It also tells us that Offa was a pragmatist, and was not about to do anything that was not strictly necessary. It is known that Offa lost Mercian land to the kingdom of Powys in the mid-eighth century, and David Hill regards the Dyke as a fallback position to ensure that there were no further incursions into his territory.

The massive expansion of Mercia in the eighth century gave it control of land to the south and east, including, as we have seen, London, Kent and Sussex. If not actual control, Mercia also managed to impose significant influence on Essex, Surrey and East Anglia. Wessex somehow retained its independence. After Offa’s death these new territories were kept within Mercian control by Cenwulf (796–821), but his successor, Beornwulf, could not stem the tide of increasing resentment against Mercia. In the year 825 he was defeated by King Egbert of Wessex at the Battle of Ellendun, and with the battle went Kent, Sussex, Surrey and Essex.

We have seen how the Norse raids began a few years before 800, and for the next three centuries Scandinavian raiders, soldiers and settlers were to play an active part in the development of early medieval Britain. It would be a mistake to think of this time as some sort of ‘Viking Period’, because many parts of Britain remained largely unaffected by these events. It would also be an exaggeration, because although Scandinavian people did influence certain areas a great deal – Viking York or Jorvík, which was captured by the Danish ‘great army’ in 866, is the obvious example – the language and basic culture of most of Britain remained fundamentally the same. In England, families born to the new arrivals often adopted Christianity and soon spoke the native language (Old English). The changes brought about by the Scandinavian ‘presence’, as J.D. Richards *has termed it, were much less far-reaching than the earlier adoption of an Anglo-Saxon way of life, which happened in the three or so post-Roman centuries.

The earliest Viking raids were essentially hit-and-run affairs aimed at rich coastal targets such as monasteries. Monkwearmouth, made famous some sixty years previously by that extraordinary genius the Venerable Bede, was just such a site. After persistent raiding it, and its twin monastery at Jarrow, were abandoned by the monks around 800. Scandinavian raiding turned to settlement quite rapidly in certain outlying areas of Britain, such as the north-western isles of Scotland and the Isle of Man. Strangely, perhaps, Wales seems to have been missed. The story of Norse raiding and settlement in England is recorded in some detail in The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles . This, or rather these , accounts are a fascinating mixture of history and propaganda.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles is one of the most important pre-Norman histories of Britain. 9 It was established by King Alfred sometime in the 890s. In form it was an annal written in Old English, which was maintained and updated at major ecclesiastical centres, where the monks’ choice of the events worthy of record often reflected local concerns, such as the appointment of a new bishop. Happenings in more distant parts of Britain often failed to get a mention. Julian Richards describes his excitement on being allowed actually to read a copy of the Chronicles in the library at Corpus Christi College, Oxford. 10 Like most archaeologists he was extremely keen to read at first hand the account of the Lindisfarne raid of 793. But he was to be sadly disappointed. The copy before him had been made in Winchester, where such far-off events were not thought worthy of inclusion.

The Chronicles begin with the Roman invasion, the account of which was mainly based on Bede, and they were still being updated in the mid-twelfth century, when the project was dropped. Surviving manuscripts are associated with Canterbury, Worcester, York and Abingdon. As Julian Richards discovered, the Chronicles can be patchy as a reliable source on early events, but are much better in their later coverage of the reigns of Alfred (871–99), Æthelred (865–71), Edward the Confessor (1042–66) and the Norman kings. Initially King Alfred set the project in motion for political ends. It was written to glorify his deeds, his reign and the emerging English nation. It does not give the other side of the story. For that, we will shortly turn to archaeology.

We learn from The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles that there was a ‘great army’ from Denmark in eastern England from 865. This force was highly mobile, and it took York the following year. It then went on to capture additional territory in the north of England (Northumbria), the Midlands (Mercia) and East Anglia. This was the land which became known in the eleventh century as the Danelaw – the area in which customary or day-to-day law (for example the rules of land ownership and local government) was influenced by Danish practice.

Alfred, King of Wessex, who ruled from his capital at Winchester from 871 to 899, is generally acknowledged as the first king of England. According to The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles his reign was largely given over to wresting eastern England back from Viking domination. Historians have painted him as an appropriately heroic figure. He is seen as the Great Man who founded England. As the Chronicles which he so astutely set up portray him, he is very much the English hero to the Viking villain. His principal contemporary biographer, Bishop Asser, was a churchman who was recruited to the royal court by Alfred. He wrote his Life of Alfred by 893, and this is the source that most historians draw upon. Laying aside the question of its authenticity, it can hardly be seen as unbiased, written as it was by someone who enjoyed the fruits of royal patronage. Moreover it draws heavily upon The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles , which were themselves a source of pro-Alfred propaganda. Subsequent historians and politicians have added much to this already impossibly noble image. We probably lack the independent sources to form a truly balanced picture of Alfred, but recent work suggests that he may at least have been human rather than superhuman. 11 It cannot be denied that while he was a sufficient master of ‘spin’ to make many modern politicians green with envy, his real and lasting achievements were many. He was a ruthless ruler who understood the importance of public opinion. He was the right man for the times in which he lived.

The bare facts of Alfred’s life are clear. He was the youngest brother of King Æthelred I of Wessex. Æthelred fought the first Danish waves of attack on Wessex, which were launched in the autumn of 870 from bases in East Anglia. Eventually he was killed on campaign in April 871. Alfred inherited the throne of Wessex aged just twenty-two. He had already assisted his elder brother in his campaigns against the Danes, and he continued the war vigorously. The Danish Great Army was to be no pushover, however.

Читать дальше