KATIE HICKMAN

Daughters of Britannia

The Lives and Times of Diplomatic Wives

Dedication Dedication List of Principal Women Introduction Prologue 1. Getting There 2. The Posting 3. Partners 4. Private Life 5. Embassy Life 6. Ambassadresses 7. Public Life 8. Social Life 9. Hardships 10. Children 11. Dangers 12. Rebel Wives 13. Contemporary Wives Plates Keep Reading Bibliography Index Acknowledgments List of Illustrations About the Author Author’s Note Notes Also by the Author Copyright About the Publisher

For Beatrice Hollond,a diamond amongst friends

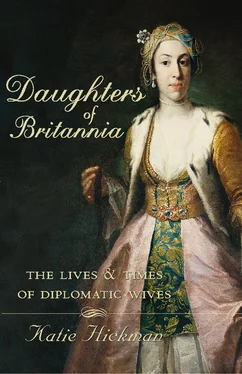

Cover

Title Page KATIE HICKMAN Daughters of Britannia The Lives and Times of Diplomatic Wives

Dedication Dedication Dedication List of Principal Women Introduction Prologue 1. Getting There 2. The Posting 3. Partners 4. Private Life 5. Embassy Life 6. Ambassadresses 7. Public Life 8. Social Life 9. Hardships 10. Children 11. Dangers 12. Rebel Wives 13. Contemporary Wives Plates Keep Reading Bibliography Index Acknowledgments List of Illustrations About the Author Author’s Note Notes Also by the Author Copyright About the Publisher For Beatrice Hollond,a diamond amongst friends

List of Principal Women

Introduction

Prologue

1. Getting There

2. The Posting

3. Partners

4. Private Life

5. Embassy Life

6. Ambassadresses

7. Public Life

8. Social Life

9. Hardships

10. Children

11. Dangers

12. Rebel Wives

13. Contemporary Wives

Plates

Keep Reading

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

List of Illustrations

About the Author

Author’s Note

Notes

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

A List of the Principal Women in the Book and the Primary Places Where They Served

| Seventeenth Century |

Date first went abroad |

| The Countess of Winchilsea (Constantinople) |

1661 |

| Ann Fanshawe (Portugal, Spain) |

1662 |

| The Countess of Carlisle (Moscow) |

1663 |

| Katharine Trumbull (Paris) |

1685 |

| Eighteenth Century |

| Countess of Stair (Paris) |

1715 |

| Mary Wortley Montagu (Constantinople) |

1716 |

| Mrs Vigor (St Petersburg) |

1730 |

| Miss Tully (Tripoli) |

1783 |

| Emma Hamilton (Naples) |

1786 |

| Mary Elgin (Constantinople) |

1799 |

| Nineteenth Century |

| Elizabeth Broughton (Algiers) |

1806 |

| Elizabeth McNeill (Persia) |

1823 |

| Harriet Granville (The Hague, Paris) |

1824 |

| Anne Disbrowe (St Petersburg) |

1825 |

| Mary Sheil (Persia) |

1849 |

| Isabel Burton (Brazil, Damascus) |

1861 |

| Mary Fraser (Peking & Japan) |

1874 |

| Victoria Sackville (Washington) |

1881 |

| Mary Waddington (Moscow) |

1883 |

| Catherine Macartney (Kashgar) |

1898 |

| Susan Townley (China, Washington) |

1898 |

| Twentieth Century |

|

| Ella Sykes (Kashgar) |

1915 |

| Vita Sackville-West (Persia) |

1926 |

| Marie-Noele Kelly (Brussels, Turkey) |

1929 |

| Norah Errock (Iraq) |

1930 |

| Iona Wright (Trebizond, Ethiopia, Persia) |

1939 |

| Evelyn Jackson (Uruguay) |

1939 |

| Pat Gore-Booth (Burma, Delhi) |

1940 |

| Diana Cooper (Paris) |

1944 |

| Diana Shipton (Kashgar) |

1946 |

| Masha Williams (Iraq) |

1947 |

| Peggy Trevelyan (Iraq, Moscow) |

1948 |

| Maureen Tweedy (Persia, Korea) |

1950 |

| Felicity Wakefield (Libya, the Lebanon) |

1951 |

| Ann Hibbert (Mongolia, Paris) |

1952 |

| Jennifer Hickman (New Zealand, Dublin, Chile) |

1959 |

| Jane Ewart-Biggs (Algeria, Paris, Dublin) |

1961 |

| Veronica Atkinson (Ecuador, Romania) |

1963 |

| Rosa Carless (Persia, Hungary) |

1963 |

| Angela Caccia (Bolivia) |

1963 |

| Sheila Whitney (China) |

1966 |

| Jennifer Duncan (Mozambique, Bolivia) |

1970 |

| Catherine Young (Syria) |

1970 |

| Annabel Hendry (Black) (Brussels) |

1991 |

| Chris Gardiner (Kyiv) |

1994 |

| Susie Tucker (Slovakia) |

1995 |

‘English ambassadresses are usually on the dotty side, and leaving their embassies nearly drives them completely off their rockers.’ These words, from Nancy Mitford’s classic vignette of embassy life Don’t Tell Alfred , were like a mantra of my youth. As children, my brothers and I used to chant them to my mother, in those days a British ambassadress herself, in her vaguer moments. Not because she was dotty (well, only occasionally) but because we knew, beyond doubt, that all other ambassadresses were.

From an early age, we were used to the tales of former ambassadresses – mad, bad and dangerous to know, they came to form part of our family culture. In New Zealand, my father’s first posting as a young first secretary, there was the delightfully distraite Lady Cumming Bruce. She was far more interested in her painting than in her diplomatic social engagements, which often slipped her mind completely; according to legend, she could regularly be spotted crawling through the residence shrubberies, so as not to be spotted arriving late for her own parties. ‘Dear Mummy and Daddy,’ my mother wrote to my grandparents just a few months after her arrival in Wellington, ‘Lady Cumming Bruce is very vague and difficult to pin down – says she’ll do something and then doesn’t. When Helen * went onto their boat to greet them on arrival she suggested to Lady CB that she should perhaps put her hat on before meeting the press. Lady CB opened her hat box inside which instead of a hat, was a child’s chamber pot.’

During the twenty-eight years that my mother spent as a diplomat’s wife, she wrote letters home. Today, at my parents’ house in Wiltshire, in amongst the paper rubbings from the temples at Angkor Wat, the Persian prayer mats and the bowls of shells from the beaches of Connemara – the legacy of a lifetime’s wanderings – there is a carved wooden chest which contains several thousand of them. Once a week with almost religious regularity – sometimes more frequently – these letters were written at first to my grandparents and my aunt, but then later also to myself and my two brothers when we were sent home to boarding school in England. During the last ten years of her travelling life it was not unusual for her to write half a dozen letters a week, recording all the vicissitudes of diplomatic life.

In these days of instant communications, of faxes and e-mails and mobile telephones, it is hard to describe the extraordinarily intense pleasure of what used, in old fashioned parlance, to be called ‘a correspondence’. As a bitterly homesick ten-year-old at boarding school for the first time, I found in my mother’s letters an almost totemic significance. The main stairs of my school house wound down through the middle of the building around a central well; in the hall below was a wooden chest on which the post was always laid out. For some reason only the housemistress and the matron were permitted to use these stairs (the rest of us were confined to the more workaday stone stairs at the back of the house), so the trick was to crane over the banisters and try to spot your letters. From two storeys up it was impossible to read your name but, to a practised eye, the form of a certain handwriting, the shape of a certain envelope, its colour or its thickness, were all clues.

Читать дальше