1 ...6 7 8 10 11 12 ...23 During a plague of typhus in Caserta, north of Naples, my dad’s unit was billeted in the abandoned royal palace, with its water cascades and hanging gardens, while for several weeks the Allied advance was held up by the battles for the monastery at Montecassino. Driving through the streets in a truck, he saw an old man fall over and die. Some soldiers who ventured out on the town in their free time suffered the same fate. Sometimes there was nothing to be done, except withdraw, observe and wonder what it was that made such things go on in the world. A degree of separation, if there was a choice, afforded a perspective that was lost on the unthinking crowd. On Piazzale Loretto in Milan, he saw the bodies of Mussolini and his mistress hanging from their heels and urinated on by an angry mob. Weeks before, the same crowd might have been cheering them.

After the war, soldiers rarely volunteered their recollections. They only came out over the years. Experiences had either been too awful, mundane or similar to those of many others to merit earlier mention. Besides, the cities at home had had the bombs. Even Sandy High Street was machine-gunned by a German fighter, my nan having to launch herself into a shop doorway with baby and pram. Anyone who went on about moments they had endured abroad in face of the enemy, or how many of them they’d injured or killed, would have been a suspect personality. Few, too, were asked. Until prompted, my dad said little more than he had seen the eruption of Vesuvius, from Caserta, filling the sky with black smoke for three weeks in March 1944. As in the time of Pompeii, the prior impression had been that it was extinct. Further north in Siena he began to learn Italian by walking out from the city’s fort and reciting door numbers. He came home speaking the language well, one among very few of the quarter of a million Allied soldiers in Italy to do so.

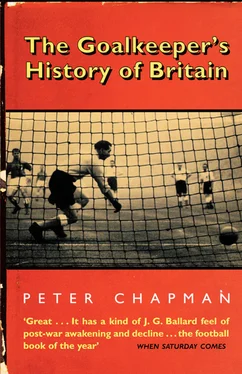

Talking about the football, rather than the war, was easier. Games were played between stages of the Allied advance up the Italian leg. My father played in goal for 15th Army Group HQ and was nicknamed ‘Flash’, though only, he insisted, after his white blond hair. You changed in barracks or tents and, if playing away, went by army truck. Match locations ranged from the landing strip in Syracuse, to Rome’s Dei Marmi stadium, encircled by statues of emperors and gods. In the Comunale stadium in Florence, England were to draw 1–1 some seven years later and maintain their unbeaten record against Italy. In Bologna, my dad occupied the goal where David Platt volleyed the last-minute winner past Preud’homme of Belgium in the 1990 World Cup. His reports of the games he played in suggest he’d have probably saved it.

As for the spectacular moments, the most memorable was reserved for when the army had moved far north to the Yugoslav border to fend off Tito’s claim to Trieste. It was made in the small stadium in Monfalcone, on a baked-earth goalmouth full of large stones. A brisk advance by the opposition down the right-wing forced him to cover his front post. But the ball swung over to the fast-advancing centre-forward, who volleyed it hard towards the far corner. A Liverpudlian, naturally vocal, the centre-forward was shouting for a goal from the moment he hit it. My dad made it across the full 8 yards of his goal, diving to push the ball away with his right hand. The save was unique in anyone’s recollection, though others may have emulated it since.

Immediate thoughts of self-congratulation were tempered by the impact of the goalmouth surface on his knees. As my dad pulled himself up in pain, his opponent – driven by a fit of frustrated expectation and Adriatic sun – rushed in, yelling and hammering him with his fists around the shoulders and head. This incident was ‘comical’, which left me with the impression goalkeepers were not averse to gaining pleasure from the annoyance of others. But they also performed an important public service. Contrary to a common prejudice that it was keepers who, by virtue of their role and isolation, were insane, they showed that it was out there, in the wider, collective world, where madness was to be found.

At the start of the war, Frank Swift had signed up as a special constable in Manchester. He was put to directing city traffic, an ill-advised move, since his presence was more likely to attract a crowd than clear it. One congested day on Market Street, with his efforts achieving nothing, he waved a cheery ‘bugger this’ and went home. Like many top footballers, he became a trainer to younger soldiers who were about to be shipped abroad. My dad was trained by Roy Goodall, the Huddersfield Town and England half-back, and passed out as a PT instructor. This qualified him for a comfortable home assignment in one military gym or another but before one arose he was en route for Africa. Again, he said, he was fortunate. Many of the younger trainers who were at first kept back from service abroad, found themselves later pitched on to the beaches at Normandy.

Football at home ticked over, with teams raised from whoever was on hand on any given Saturday. Sam Bartram played in two successive wartime Cup Finals, one for Charlton, the other as a guest for Millwall. As the war moved towards conclusion, opportunity arose to put on exhibition matches for the troops abroad. Victory in Europe was on the point of being declared as my dad’s unit progressed to Florence, when it was announced Frank Swift was due in town. He was to play for a team led by Joe Mercer, the Everton half-back, against that of Wolves captain, Stan Cullis. It was to be an occasion for great celebration, till on the morning of the game, my dad and fellow signalmen were told to pack their kit and advance up country to Bologna. VE Day was an anti-climax. Each soldier was issued two bottles of beer, which he and his mates poured over their heads: ‘Bloody stupid, really.’

Full international games were under way at home more than a year later. It was obvious to many that the choice for the England keeper lay between Swift and Bartram. In conversation their names were mentioned in the same breath. Yet, in an era when the average forty-year-old didn’t have a tooth to talk of, at thirty-two they weren’t young. The England selectors had dallied with the idea of jumping a goalkeeping generation. Ted Ditchbum of Tottenham Hotspur, ten years younger, was the object of their attention. He had played well in big wartime games against Scotland and Wales, which suggested he was in for a promising international career. Unfortunately for Ditchbum, the Royal Air Force thought so as well. When he was posted to the Far East for two years, the selectors’ hand was forced. By default as much as instinct, they tossed the keeper’s yellow jersey, undersized for the part, into the huge grasp of Frank Swift.

He played commandingly in the first seventeen internationals after the war. For two, he was selected as England’s first goal-keeping captain. What he described as his own greatest day was when he led the team against Italy in May 1948. Originally England were to play Czechoslovakia but after February’s communist coup in Prague, the fixture was rearranged. The team went by air from Northolt, a dozen journalists in tow, among them former players like Charles Buchan, ex-Scotland and Arsenal and then of the News Chronicle. The mode of transport, however, was sufficiently novel for the Daily Herald’s man to opt to go by boat and train. The weather deteriorated over Switzerland, where the captain felt it necessary to stop and change planes. Swift described the rest of the journey over the Alps in a twin-engined Dakota as a ‘bit of a snorter’ and said he wasn’t the only passenger relieved to get off again.

The match was on Juventus’s ground in Turin. World Cup holders from before the war and in front of their own 85,000 crowd, the Italians were expected to win. While England had given themselves three days to prepare, the home team had been undergoing three weeks’ intensive training. Continentals clearly took this kind of thing very seriously. Furthermore, where England’s training in Stresa was open to view, recorded Swift, Italy’s was ‘at a mountain hideout’. In the England dressing room, there was no concealing the pre-match tension: ‘We knew what we were up against and changed quietly.’ Come the moment, Swift was unable to find the words for a captain’s speech of encouragement. Instead, each member of the team filed past and shook his hand.

Читать дальше