It is obvious that the effect of wind on the outer coasts is very great, for there is not only the period of great gales in the winter, when there are no leaves on the shrubs and no leafy vegetation at ground level, but there is the continual wearing of the summer period. I have seen leaves die from shaking through three days of blowing. Such trees as exist take on a distorted appearance, not one branch or twig managing to survive on the windward side of the trunk. It is a remark commonly heard that a tree has been bent by the constant action of the wind, but this is not true. Distortion is brought about by the continual lack of survival of all growth on one side. The distal ends of twigs are killed and the tree develops more and more a fuzziness of short annual shoots from the main stem. The influence of wind on the coastal region is further complicated by the spray which it may carry, for most broad-leaved plants object to a deposition of salt on their foliage. This is a subject we shall touch on later in the book.

North winds are relatively uncommon in the Highlands, but are recognized as bringers of snow in winter, snow which sets up its own train of events in natural history. A north wind in June or July means the best of sunny weather, but in August the north wind brings rain. East winds blow most regularly in spring, but gales from the south-east occur as well in the West Highlands. They are very cold for the district, as the south wind can be as well, for the air has come over a mountainous region where it must become chilled. The southeasters are dry winds and have a desiccating effect on the autumn herbage, sufficient to curtail the grazing season in some years. The south winds of summer mean a leaden sky and rain.

To conclude, the climate of the Scottish Highlands and Islands is rapidly changeable and far from uniform. The coastal climate is maritime or oceanic, but in the Central and Eastern Highlands it is more continental—more extreme temperatures, less wind, less rain and drier air. The meteorological tendency to drier air in the central region and the Dee Valley is further added to by the capacity of the ground to drain rapidly.

RELIEF AND SCENERY

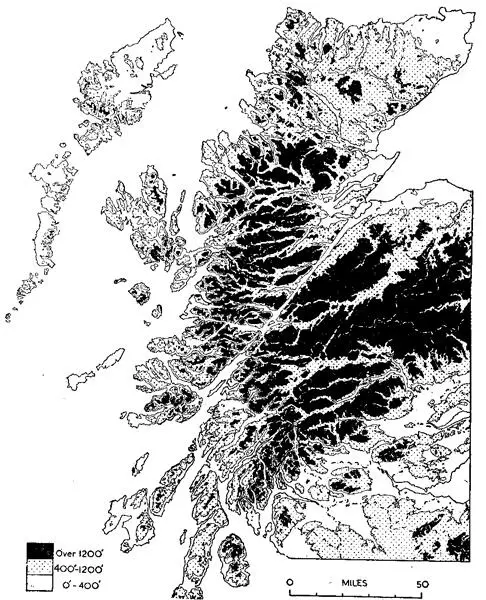

LET US look at a physical map of Scotland and allow ourselves to make a tour of the Highlands as observers of country rather than as naturalists making detailed studies of habitats. We shall then be able to see those habitats with eyes wider open for the comparative sense we shall have gained. It will be convenient to divide the Highlands into five zones to which we cannot fairly give definite boundaries, though the zones themselves are significant in natural history. The divisions are my own and do not carry the weight of the acceptance of a committee of biologists. I should call them:

1 The southern and eastern Highland fringe which is in effect a frontier zone.

2 The Central Highlands, which may be likened to a continental or alpine zone.

3 The Northern Highlands, a zone with sub-Arctic or boreal affinities.

4 The West Highlands south of Skye, which may be called the Atlantic or Lusitanian Zone.

5 The Outer Hebrides and islands of Canna, Coll, Tiree, and such small islands as the St. Kilda group, the Treshnish group, the Flannans, North Rona and Sula Sgeir; an oceanic zone.

THE SOUTHERN AND EASTERN HIGHLAND FRINGE

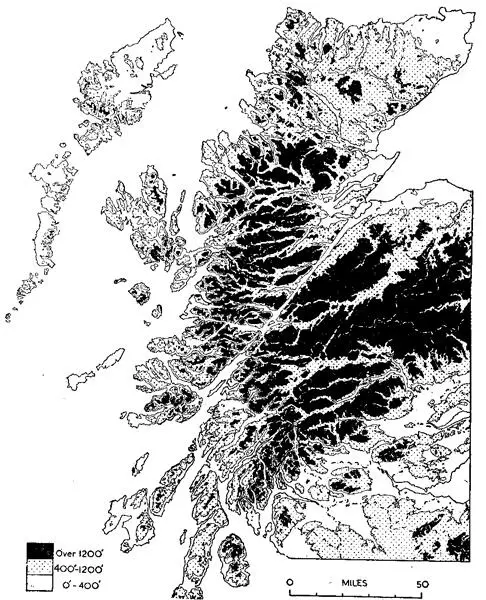

FIG. 4.—Generalized relief features of the Highlands By courtesy of the Land Utilisation Survey of Great Britain

This zone follows the line of the Highland Border Fault from Helensburgh almost to Stonehaven, and then turns at right angles north-westwards to include the middle Dee. The Lochnagar massif, 3,786 feet, may properly belong to the Central Highland zone, but it is a good pivotal point and its long southern slopes all drain into the eastern plain below the Highland Border Fault. From Lochnagar we can cross to Pitlochry and thence to Loch Tay and south-westwards to the head of Loch Lomond and to the sea at the head of Loch Fyne.

The land to the south and east of this zone is highly productive agricultural ground which shows some of the best farming in Scotland.

The zone itself is largely occupied by sheep farms which graze the Blackface breed, but the farther north-eastwards we go from Cowal to the Glens of Angus the better are the sheep, and the same hills on which they graze become easier and better grouse moors. That part of the zone east of the Tay Valley has a very high value as grouse moors for they are among the best in the kingdom. There are also deer forests in the area—west of Loch Lomond where cattle and sheep are also grazed, the Forest of Glenartney, south of Loch Earn and east of Loch Lubnaig, and Invermark Forest south of Lochnagar and in the upper reaches of the Glens of Angus.

The changing nature of this zone within historical time may be gathered from such names on the maps as Forest of Alyth and Forest of Clunie. There would be a large number of trees there hundreds of years ago, but the word forest would be given in the particular connotation of a large uncultivated tract, a usage of the word with which we are more familiar in the Highlands where a deer forest may be practically treeless. The Forests of Clunie and Alyth are now places of rearing farms for cattle and sheep, though, of course, there are still large areas of grouse moor. The golden eagle has gone from here, no longer tolerated by grouse-shooters and the farmers, and the country is not rough enough to give it sanctuary. But in Invermark Forest at the head of the Angus Glens the eagle is given protection. One might say that the red deer have gone from the forests of Clunie and Alyth, and so they have as full residents. This, however, is a frontier zone by our definition, and in winter and hard weather the stags come down the long glens of Glen Isla, Glen Fernait and Atholl. It is in this zone that there is so much outcry against the deer, which become such predatory bands on young corn crops, fields of turnips and potato clamps. A fair amount of coniferous timber is grown in this northeastern area of the frontier zone because the climate is fairly dry and the drainage good.

Dunkeld is one of the gateways to the Highlands proper, at the foot of Strathtay. From Dunkeld to Pitlochry we are in a valley made famous by an earlier Duke of Atholl in his zeal for planting. Larch became one of our most important conifers after the Duke had planted it so extensively during the 18th century. It is interesting to note, also, that it is in this afforested country that the new hybrid between the European and Japanese larch has occurred by a fortunate accident. The hybrid, with its hardiness and immunities, is expected to be a notable forester’s tree in the future. All this area and that already described carries a big stock of roe deer. Despite its unpopularity with the forester, the roe happily persists, apparently as strong as ever.

West of Dunkeld we are into Strath Bran, still timber country, grouse moors and rearing farms. The fauna of Highland hills are constantly pressing down into this zone and are as surely being scotched before the plain of Strathmore is reached. Peregrine falcons, wild cats, eagles, foxes, red deer—all these come through and rarely return. There are no high tops in this area until the head of Glen Almond where the summit of Ben Chonzie, 3,048 feet, dominates everything else in the district; yet there is big country here which the relative smoothness of the hill faces tends to emphasize. The streams have good brown trout and the valleys are always well wooded among the numerous farms. The bird population is rich and varied.

Читать дальше