The bread had arrived while I was chatting and the banana boat prepared to leave. This powerful vessel had twin seventy-five horsepower outboard motors and two plastic garden chairs. We powered out of the harbour and the cool wind brushed our faces and lifted our spirits. The rusting Taiwanese trawlers were soon left far behind as we sped along the south coast of Milne Bay towards East Cape. A young village girl carrying some shopping sat in the seat beside me. She prattled on in Pidgin to the two boys piloting the boat but they said nothing at all to me. I put my feet up – one on a carton containing an electric lawn mower and the other on a carton of several hundred tins of baked beans. The dinghy began to buck as we headed towards the open ocean and I noticed there were no life jackets. Later I was to learn that this omission is quite normal practice. I would have felt decidedly wimpish to have mentioned this in such a ‘masculine’ society. Be a man and drown or laugh as you are taken by a shark. My panama began to whip around my legs as I held it down out of the wind.

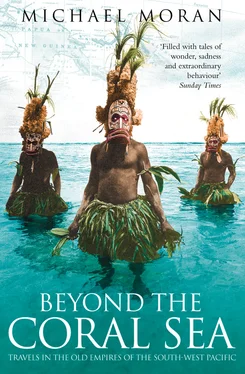

We followed the coast east for only a short time, sailing parallel to the road I had travelled only a couple of days before. The sea became rougher as we turned south towards Samarai and the Coral Sea. I felt a tremendous sense of exhilaration, my face dashed with spray, slicing through the azure water, the dark-green jungle defending the mountainous interior coming up on the right. Coconut palms, transparent green water fringing crystalline beaches, a swirl of smoke from the occasional bush hut. Young, brown, white-breasted sea eagles soared on the up-draughts, their wingspans majestically spread against the vegetation. Fragile outrigger canoes weathering the sea swell were cheered on by the boys.

The currents in China Strait are treacherous. The pattern on the surface of the water changes from seahorses whipped by the wind to smooth powerful eddies of deep blue streaming up from the abyss. The pastel outlines of numerous small islands appeared, jagged peaks lifting from valleys shaped like cauldrons. The sun broke through gunmetal clouds and burnished the sea, biblical rays that appeared to be guiding us to salvation. I realised with surprise I was soaked to the skin.

Captain John Moresby landed on Samarai from HMS Basilisk in April 1873 hoping to evade the unwelcome attentions of his ‘savage friends’. He settled down to dinner with his officers but they were followed by a hundred fighting men, who squatted quietly on the beach beside the blue water and watched the proceedings with close interest. Moresby offered them a stew made of preserved soup and potatoes, salt pork, curlew and pigeon, which, not altogether surprisingly, disgusted the warriors. The sailors unsuccessfully tried paddling canoes which resulted in capsizals, hilarious moments for all concerned. The warriors opened the officers’ shirts and stroked the white skin of their chests in wonderment and appreciation. Captain Moresby wryly named the place Dinner Islet to mark this unusually human and peaceful encounter. The local name of Samarai soon replaced the cannibalistic associations of the former.

The island appeared a deserted ghost town at first sight. The former provincial headquarters, which is an older settlement than Port Moresby, had clearly seen better days. I climbed up onto the Orsiri trading wharf to take my bearings. Ruined warehouses lined the neglected International Wharves site, warehouses gaping like skulls set on a rack, the empty interiors propped up by partitions of broken bone. Planks and beams jutted out like shattered teeth. Clumps of resentful youths were loitering around the general store and glared at me without a smile, but the women and children greeted me with friendly waves.

‘ Apinun! ’ 1

‘ Apinun! ’

The mown grass and coral streets (there is only one rarely used motor vehicle on Samarai) seemed like sections of an abandoned filmset. I walked between the abandoned shells of two buildings in which some boys were shouting and playing football. I hoped I was heading towards the Kinanale Guesthouse, run by Wallace Andrew, the grandson of a cannibal. Some attractive colonial houses were ranged around the perimeter of a waterlogged football field. In the sultry heat I leant exhausted against an electricity pole near a memorial obelisk before heading for a small beach in the distance. Rain trees and old flamboyants offered cooling shade.

‘Hello there!’ The voice came from a porch at the top of a flight of steps to my left. ‘Come up and have a drink!’

A tall, smiling ‘whiteskin’ wearing shorts, his legs covered in the ubiquitous small plasters, beckoned me in.

‘I’m looking for the guesthouse run by Wallace Andrew. Do you know where it is, by any chance?’

‘It’s just there!’ and he pointed to a large house partly covered in old wooden scaffolding. I had thought this structure was an abandoned building project.

‘Wallace is about somewhere, but come up for a minute.’ He disappeared inside.

I went into the sitting room and collapsed into a chair while he brought some iced water from the fridge. Furniture was clearly hard to come by on Samarai and the room had the feel of a temporary arrangement that had drifted out of control into permanence. For no good reason I imagined I could see mosquitoes everywhere. Probably the beginnings of tropical madness.

‘Hi, there. I’m Ian Poole, Manager of Orsiri Trading.’ I instinctively felt he was open and lacking in the customary consuming demons, a rare quality in the tropics, although it was a slightly mad challenge maintaining a business in this remote spot. Australians generally manage extremes with equanimity and dry humour.

‘I’m just travelling the islands. Chris Abel from Masurina told me to look you up. I’ve heard you have an encyclopaedic knowledge of the place.’

‘Well, it’s certainly interesting. Wallace knows a lot more about the local villagers and Kwato Mission, of course. He was born there.’

‘I’m surprised there are so many old buildings left. Didn’t the Australians carry out a scorched-earth policy to stop the Japanese?’

‘Yes. Unnecessary, though. The Japs buzzed the island a few times in flying boats and dropped a couple of bombs but that was it. The Aussie Administration Unit set fire to all the commercial and government places including the famous hotels. Tragic loss. You can still see the few survivors around the football pitch.’

Missionaries were the first Europeans to establish themselves in this part of Eastern Papua New Guinea. By 1878 the Reverend Samuel MacFarlane had made Samarai a head station for the London Missionary Society, but the LMS soon exchanged land on Samarai for the island of Kwato a short distance away. At the turn of the century Samarai had no wharf or jetty and goods were off-loaded from trading vessels into canoes. It was a government station, a port of entry and a ‘gazetted penal district’. Local labour was forcibly recruited here for the plantations. Copra and gold-mining dominated life, and this tropical paradise became a more important centre than Port Moresby. The town, if it could be described as such, consisted of ‘The Residency’ (a bungalow built on the only hill for the first Commissioner General, Sir Peter Scratchley, appointed by the Imperial Government in 1884 and dead from malaria within three months), the woven-grass Sub-collector’s House, the gaol (with the liquor bond store in the roof), the cemetery and Customs House, and two small stores plus a few sheds. There were no hotels or guesthouses in the early days of the 1880s, the traders living mainly on their vessels and the gold-diggers camped out in their tents.

The Europeans besieged Whitten Brothers’ premises since alcohol was dispensed from their store. The empties were hurled onto the sand from the roofed balcony. A village boy collected the bottles the next morning and counted them. Whitten then divided the number of bottles by the number of men drinking and so accounts were democratically settled. According to the entertaining reminiscences of Charles Monkton in his book Some Experiences of a New Guinea Magistrate published in 1921, men dressed mainly in striped ‘pyjamas’ or more festively in ‘turkeyred twill, worn petticoat fashion with a cotton vest’. He describes picturesque ruffians roaming the palm-fringed shore. One incorrigible known as ‘Nicholas the Greek’, after pursuing an absconder through impenetrable jungle, returned with only his head in a bag. When questioned about the missing body he laconically commented, ‘Here’s your man. I couldn’t bring the lot of him, so I’ll only take a hundred [pounds].’ Monckton also describes ‘O’Reagan the Rager’, who was ‘never sober, never washed, slept in his clothes, and at all times diffused an odour of stale drink and fermenting humanity’. The spectacular sunsets and moonlit tropical nights of Dinner Island had formed a cinematic backdrop to all types of mysterious schooners, yawls, ketches, cutters and luggers with eloquent names such as Mizpah, Ada, Hornet, Curlew and Pearl.

Читать дальше