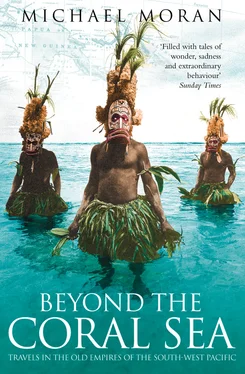

As I slowly headed out to sea, superb tropical fish and a kaleidoscope of soft corals were laid out beneath me like a living carpet. Visibility in these glassy waters can be as much as fifty metres. Tiny electric-blue fish formed constellations around isolated outcrops of rock; rainbow fish swam lethargically away to shelter beneath the coral shelves; butterfly fish abstractly painted in swathes of luminous purple and chrome yellow shot into crevices; black and wild-green specimens with long, pointed mouths ignored me completely; gossamer-thin angel fish flowed in the crystal current like fabric; fantastic lacy scorpion fish mimicked plants and defied my most careful observation. The seabed as far as I could see was covered with ultramarine starfish, mauve-tipped clusters of beige coral and enormous brain corals. I remained among these enchanting coral gardens for more than an hour.

Sele seemed pleased that I had enjoyed my swim until I mentioned the skull cave I knew was nearby. In the Massim the dead were buried twice. In the second interment, bones were placed on rock shelves overlooking the ocean, or in dank underground holes near the shore. The cave was five minutes from the village, but no one would agree to show me the place. There remains a great fear of sorcery and witchcraft in Milne Bay. Strange apparitions still manifest themselves at sea in contradiction to mission teaching.

‘We don’t believe in such things anymore,’ Sele said not terribly convincingly.

‘Well, then, it doesn’t matter if you show me.’

He would not argue and shuffled about looking at the ground, occasionally spitting a jet of crimson, anxious to be off. The girls too had lapsed into silence.

‘The first mission school was called Under the Mango Tree. We were happy.’

As he crunched the Toyota into gear a couple of young boys chewing betel nut and dressed in sharp sports-shirts begged for a lift into Alotau. There is no bus service and hardly any transport this far along the Cape. Sele politely asked me if I minded, so naturally I agreed. They gratefully climbed into the tray behind the cab. As we jolted along I pointed to a pretty bush-material hut on stilts standing in the water and asked the girls what it was. Screams of laughter came from the back seat.

‘A toilet!’ they said after catching their breath.

Soon after leaving we were flagged down by some local Tavara villagers whose banana boat had run out of petrol during their Sunday outing. They also piled into the back. Sele ignored our precariously perched passengers despite the lurching of the vehicle, which threatened at any moment to catapult the whole laughing crew into the palms. Clearly they were accustomed to hanging on for grim death. We stopped at a small beach overhung with rosewood trees, a few rusty spikes poking up through the tide washing the sand.

‘This is Wahahuba where the Japanese landed. Wrong place! They came on a raining night and crawled under the huts. We thought they are dogs and pigs looking for dinner.’ Sele smiled with strange equanimity.

‘Were the people frightened?’ One inevitably asks trite questions concerning war.

‘Much shouting out. One meri 1 quickly grabbed up her covers thinking her baby is there, rushed away, but later she finds her bundle is empty. Terrible.’ Sele seemed almost tearful. ‘They bayonet people to keep them silent.’

On the showery night of 25 August 1942, a heavy naval bombardment preceded the attack of the Japanese Special Naval Landing Force. The Japanese began the engagement with only a vague idea of Allied strength. Neither side had been trained for living and fighting in the tropical jungle. Their equipment was inappropriate to combat the incessant rain and mud which destroyed their boots and rotted their feet. Some Australian troops who fought as part of Milne Force were young volunteers of the Militia, popularly known as chocos (chocolate soldiers) or koalas (not to be sent overseas or shot). They had trained sporadically at home during their free time. A great deal of ill-feeling, known as the ‘choco smear’, was expressed towards the Militia by the professional, battle-hardened troops of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) who had recently fought bravely in Tobruk in the Middle East. ‘Scum, scum, the Militia may kiss my bum,’ they would chant derisively. 2

The Milne Bay Battle was problematical and confused. Troops had suffered from seasickness on the stinking hulks that brought them to New Guinea. The only food was Bully Beef and ‘Jungle Juice’ distilled from palms. Coconuts fall when the stem swells with moisture, and after rain these missiles killed and injured many men. The troops glowed a livid shade of green from skin treatments and dye bleeding from their wet tropical uniforms. There were no proper maps, only rough sketches of the terrain and their radios were useless. No mosquito nets had been provided. A malignant strain of tertian malaria laid low more than half the fighting force through ignorance of correct preventative measures. Equipment was inadequate. No one knew what was going on.

By dawn of 27 August the Japanese were pinned down by intense strafing by Kittyhawk fighter aircraft of the RAAF (Royal Australian Air Force), some flown by former Spitfire pilots. These ‘flying shithouses’ (as they were affectionately known) were polished with beeswax for speed, but the rain and ooze made flying conditions an indescribable nightmare. Fighters slid off the runway and collided with the bombers. One of the Japanese officers, Lieutenant Moji, became physically ill at the protracted onslaught and in his diary noted in his oddly mechanistic way that ‘the tone of our systems was feverish and abnormal’. However, moments of humour were ever present. Some Japanese soldiers attempted to confuse the Australians by shouting unlikely phrases in English.

‘Is that you, Mum?’ was rapidly answered by a burst of machine-gun fire.

Another four-wheel-drive had become stuck in the riverbed just in front of us. Sele contemplated the scene of impotent activity for a long time. He suddenly gunned across the torrent, all the while being egged on with shouts of excitement and delight from our precariously-positioned passengers. More picturesque tropical beaches were glimpsed through the palms until we encountered the final memorial which marked the western- and southernmost point of the Japanese advance. Some eighty-three unknown Japanese Marines, who made a suicidal charge against impossible odds, lie buried here. The Japanese military maxim, ‘Duty is weightier than a mountain while death is lighter than a feather’, seemed to possess an even deeper significance in this theatre of war. Soldiers would feign death, lying open-mouthed among the fallen, and then the ‘corpse’ would suddenly spring to life and shoot an Australian or American in the back. Numbers of dead are uncertain owing to the large quantity of body parts – legs, arms, hands and heads – that were left hanging sickeningly in the trees after the explosion of bombs and shells.

We arrived back at the lodge as dusk was falling. A late afternoon storm was gathering in the mountains. ‘General’ Mocquery was seated on the veranda in his customary position near the fans talking to a tall, fair-haired man whose complexion and features betrayed all the signs of having spent many years in a tropical climate. He was wearing shorts and his bare legs carried a number of small plasters covering insect bites. Slightly damp, thinning hair accentuated his faintly feverish appearance. Mocquery in full tropical fatigues gestured for me to come over.

‘… no dental treatment available at all,’ he concluded and glanced up.

‘Good trip to East Cape?’

‘Marvellous! Went swimming. The water’s so clear!’ I felt elated.

Читать дальше