R. M. Healey in his Shell Guide to Hertfordshire is generous about the countryside thereabouts, finding in it Samuel Palmer’s elegiac landscape paintings, better Palmer’s dark etchings from his final years after he had grown angry at the plight of the agricultural labourer.

In the right weather, the wrong weather, the view belongs in the old nurse’s tale that troubled Jane Eyre’s imagination, making her think of Thomas Bewick’s engraving of a ‘black horned thing seated aloof on a rock, surveying a distant crowd surrounding a gallows’. But so would many such views in England: the historian John Lowersonhas written about the ‘popular sense of an eternal cosmic battle between good and evil that is being fought out in an essentially rural English context’. Our yew site is a place as good as any for such battles, for stories, for putting ideas in men’s heads about dragons and their slayers. Was it the place as much as the belief that a dragon once stalked those parts that would soon make them think they’d found a dragon’s lair?

Farm labourers worked from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. in the winter. Six shillings a week was a usual wage, but felling timber was paid by the load: one shilling for fifty cubic feet. You can do the working out. John Carrington’s oak we met in the last chapter would have earned them fifteen shillings. Was it blood money enough? Were they superstitious about their task that day? No doubt there were those who thought that chopping down a yew brought bad luck. Plant lore is thick with injunctions against bringing down trees. The folklorist Jeremy Harte, writing about the Isle of Man, tells of the seemingly lonely places where ‘locals know about the elder trees that should never be touched, not since the farmer hacked them back, and hanged himself in the barn that night’. But Harte is writing about fairies, and it is thorn trees and elders, not yews, that must be left alone. But a yew was also a sacred tree to many: ‘ A bed in hellis prepared for him / Who cut the tree about thine ears.’ Did the men have sentiments similar to this final couplet from an old rhyme about the Yew Tree Well in Easter Ross, Scotland? A chill warning to those wielding an axe. The Yew of Ross in Ireland had to be prayed downby St Laserian because its wood was wanted, but no one dared fell it. Recall King Hywel Dda’s tenth-century prohibition on felling yews associated with saints. Do similar injunctions survive far and wide in the collective memory? When the Victorian archaeologist Augustus Pitt-Riversremoved an old yew from a prehistoric burial mound in Dorset, the locals were not happy, even though Pitt-Rivers said the tree was dead: ‘I afterwards learned that the people of the neighbourhood attached some interest to it, and it has since been replaced.’

John Aubrey relatesthe fate of the men who felled an oak in 1657 and in passing recalls the wife and son of an earl who died after he had an oak grove removed. These tales linger and still give pause for thought today to the sensitive and cautious: Harte writes, ‘When we find that the N18 from Limerickto Ennis curves to go around a fairy thorn, we admire the knowledge of Eddie Lenihan, who campaigned to save the tree, as well as the prudence of the County Surveyor who knew of the risk involved in damaging it.’

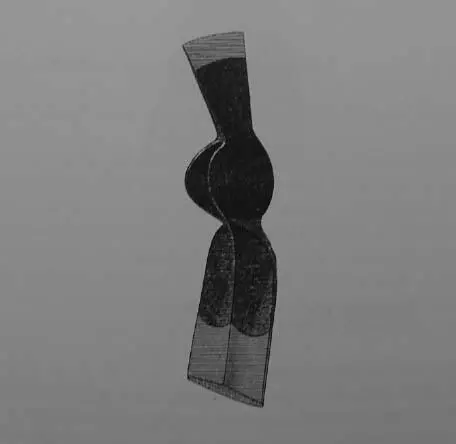

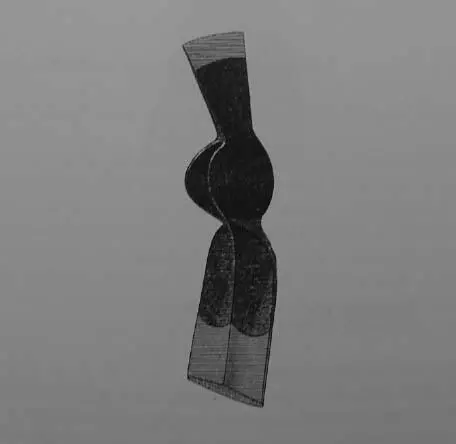

Still, the Lawrences and the Skinners had their work to do, and so they savaged the roots of the great tree. Specifically the roots, I think. There is an engraving by Turner in his Liber Studiorum called ‘Hedging and Ditching’. Two men are in a ditch in the ground fetching down a tree, not neatly chopping it down, but seeming to lever it out of the ground with pickaxes. A woman in a bonnet with a shawl over her shoulder walks by looking on. This is no rural idyll. The drawing has something in common with First World War art, with the pencil lines that suggest mud and stones, the thin leafless trees in the hedge, shredded of the fullness of trees. Grubbing up is an evocative expression. It is an unpleasant image, total and annihilating: trees torn violently from the soil. I think of Ted Hughes’ Whale-Wort torn out by the roots and flung into the sea when he just wanted to sleep. It is the slow deliberate painstaking act of men with hand tools. Those in Turner’s sketch might be doing hard labour; they look a bad lot, like pirates or smugglers – Turner was on the coast at East Sussex, so maybe they were.

Forget a neat V-shaped wedge incised with an axe prior to sawing. Dynamite and perhaps club hammers would make more sense than a copybook felling. An ancient yew with its hollows and split trunks and the irregular sprawl of its weary branches mocks the surgical approach. H. Rider Haggard, the author of the adventure stories She and King Solomon’s Mines , gives the best and most plausible description of how the tree was felled in his A Farmer’s Year: Being His Commonplace Book for 1898. He writes that there are two ways of felling a tree:

one the careless and slovenly chopping off of the tree above the level of the ground, the other its scientific ‘rooting’. In rooting at timber, the soil is first removed from about the foot of the bole with any suitable instrument till the great roots are discovered branching this way and that. Then the woodsmen begin upon these with their mattocks, which sink with a dull thud into the soft and sappy fibre.

This was known as grub-felling in East Anglia and was the common methodfor bringing down timber trees in that part of the country.

By Wigram’s account, Lawrence and the other men had an uncommon amount of trouble with those roots. Perhaps their hearts were not in it, or something held back the full strength of their axe strokes. Did one of them stroke the scaly bark that yews can slough off to get rid of infections? Did it rattle under their fingers and the sap begin to run blood red? Fred Hageneder in his Yew: A History tells us that the yew is the only European tree that can bleed red sap. A feat that is scientifically unexplained, he says. The yew at Nevern in Walesis notorious for bleeding the blood of those buried in its churchyard. A bleeding tree might have given those men – any men – second thoughts. Or did the texture of its bark look like scales from a picture book dragon? In Ulverton , his extraordinary record of a fictional village across time, Adam Thorpe channels an old carpenter in an inn in 1803 regaling a visitor with his memories. He recalls the time the master carpenter chose an oak by smell, seasoned it for two years, then made a lid for the church font. ‘Atween you an’ I, though, I can spot a dragon in them patterns. I reckons as how there were a dragon in that tree. He’ll avenge hisself one day.’ Is this a brilliant bit of invention or does Thorpe know of a folk tradition among carpenters about dragons in trees?

They kept at it, but the tree would not yield. Yet is thy root sincere, sound as the rock, / A quarry of stout spurs and knotted fangs, / Which crook’d into a thousand whimsies, clasp / The stubborn soil, and hold thee still erect.

Eventually, they took a break. ‘It was very hard work to get it down. The men had been at work all the morning, and went away to dinner,’ wrote Wigram. In one of his later letters he put the story into the mouth of a local: ‘They do say Sir, that the men could not get that yew Tree down. And at last they all went away to breakfast.’

It was an ’umbuggin job to remove such a tree. Why take so much effort to bring her down? Maybe someone wanted the timber. John Aubreyrecalls the churchyard yew of his childhood in the 1630s, ‘a fair and spreading ewe-tree … The clarke lop’t it to make money of it to some bowyer or fletcher’. The lopping killed it.

Читать дальше